by Mary Salinas | Oct 14, 2020

Stoke’s aster ‘Mel’s Blue’ 20 days after Hurricane Sally’s landfall. Notice how soil was washed away from root ball, all the leaves emerged post-hurricane. Photo credit: Mary Salinas, UF/IFAS Extension.

Hurricanes can wreak havoc in your landscape, but they can also reveal what plants are the toughest and most resilient. It’s a great learning opportunity.

A few weeks ago, Hurricane Sally came along and brought about 10 feet of surge and waves across my landscape and completely covered everything except the tallest trees for about 18 hours. (Fortunately, our house is on stilts and we did not have intrusion into our main living areas.)

As expected, the trees, including Dahoon Holly and Sweetbay Magnolia, took a beating but stayed intact. With their dense fibrous root system, most of the clumping native grasses also stayed put.

Perennial milkweed 3 weeks post-hurricane. New topsoil and compost now covers the rootball. Photo credit: Mary Salinas, UF/IFAS Extension.

The most surprising plant species that survived were about a dozen Stoke’s aster and 3 perennial milkweed. 4-5 inches of soil all around them was washed away, most of the roots were exposed, and the leaves were stripped or dead. The other perennials that had lived nearby were all washed away. To my surprise, within about 10 days after the storm, these two plant species started poking up new stems and leaves.

Here’s a list of some of the plants either in my yard or in the neighborhood that survived Hurricane Sally’s storm surge and may be suitable to add to your coastal landscape:

- Dahoon holly, Ilex cassine

- Muhly grass, Muhlenbergia capillaris

- Dwarf Fakahatchee grass, Tripsacum floridanum

- Perennial milkweed, Asclepias perennis

- Stoke’s aster, Stokesia laevis, specifically the cultivars ‘Mel’s Blue’ and ‘Divinity’

- Bottlebrush, Callistemon citrinus

- Gardenia, Gardenia jasminoides

- Bougainvillea, Bougainvillea spp.

- Flax Lily, Dianella tasmanica

- Crapemyrtle, Lagerstroemia spp.

- Cabbage palm, Sabal palmetto

- Canary Island date palm, Phoenix canariensis

- Sweetbay magnolia, Magnolia virginiana

- Augustinegrass, Stenotaphrum secundatum

- And, unfortunately, the rhizomes of the invasive torpedograss also survived.

For more information on salt tolerant and hurricane resistant plants, see:

UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions: Coastal Landscapes

UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions: Salt-tolerant Lawngrasses

UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions: Trees That Can Withstand Hurricanes

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 8, 2020

7 year old Overcup Oak (Quercus lyrata) on the edge of a wet weather pond in Calhoun County. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Haunting alluvial river bottoms and creek beds across the Deep South, is a highly unusual oak species, Overcup Oak (Quercus lyrata). Unlike nearly any other Oak and most sane people, Overcups occur deep in alluvial swamps and spend most of their lives with their feet wet. Though the species hides out along water’s edge in secluded swamps, it has nevertheless been discovered by the horticultural industry and is becoming one of the favorite species of landscape designers and nurserymen around the South. The reasons for Overcup’s rise are numerous, let’s dive into them.

First, much of the deep South, especially in the Coastal Plain, is dominated by poorly drained flatwoods soils cut through by river systems and dotted with cypress and blackgum ponds. These conditions call for landscape plants that can handle hot, humid air, excess rainfall, and even periodic inundation (standing water). It stands to reason our best tree options for these areas, Sycamore, Bald Cypress, Red Maple, and others, occur naturally in swamps that mimic these conditions. Overcup Oak is one of these hardy species. Overcup goes above and beyond being able to handle a squishy lawn, it is often found inundated for weeks at a time by more than 20’ of water during the spring floods our river systems experience.

The same Overcup Oak thriving under inundation conditions 2 weeks after a heavy rain. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

The species has even developed an interesting adaptation to allow populations to thrive in flooded seasons. Their acorns, preferred food of many waterfowl, are almost totally covered by a buoyant acorn cap, allowing seeds to float downstream until they hit dry land, thus ensuring the species survives and spreads. While it will not survive perpetual inundation like Cypress and Blackgum, if you have a periodically damp area in your lawn where other species struggle, Overcup will shine.

Overcup Oak is also an exceedingly attractive tree. In youth, the species is extremely uniform, with a straight, stout trunk and rounded “lollipop” canopy. This regular habit is maintained into adulthood, where it becomes a stately tree with a distinctly upturned branching habit, lending itself well to mowers and other traffic underneath without having to worry about hitting low-hanging branches. The large, lustrous green leaves are lyre-shaped if you use your imagination (hence the name, Quercus lyrata) and turn a not-unattractive yellowish brown in fall. Overcups especially shines in the winter, however, when the whitish gray, shaggy bark takes center stage. Overcup bark is very reminiscent of White Oak or Shagbark Hickory and is exceedingly pretty relative to other landscape trees that can be successfully grown here.

Overcup Oak leaves in August. Note the characteristic “lyre” shape. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

Finally, Overcup Oak is among the easiest to grow landscape trees. We have already discussed its ability to tolerate wet soils and our blazing heat and humidity, but Overcups can also tolerate periodic drought, partial shade, and nearly any soil pH. They are long-lived trees and have no known serious pest or disease problems. They transplant easily from standard nursery containers or dug from a field (if it’s a larger specimen), making establishment in the landscape an easy task. In the establishment phase, defined as the first year or two after transplanting, young, transplanted Overcups require only a weekly rain or irrigation event of around 1” (wetter areas may not require any supplemental irrigation) and bi-annual applications of a general purpose fertilizer, 10-10-10 or similar. After that, they are generally on their own without any help!

Typical shaggy bark on 7 year old Overcup Oak. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

If you’ve been looking for an attractive, low-maintenance tree for a pond bank or just generally wet area in your lawn or property, Overcup Oak might be your answer. For more information on Overcup Oak, other landscape trees and native plants, give your local UF/IFAS County Extension office a call!

by Mary Salinas | Oct 20, 2018

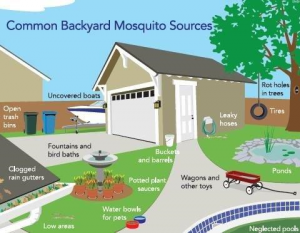

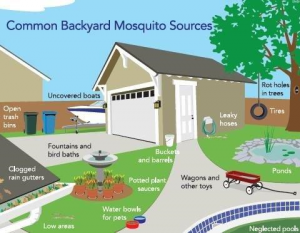

A natural disaster such as Hurricane Michael can cause excess standing water which leads nuisance mosquito populations to greatly increase. Floodwater mosquitoes lay their eggs in the moist soil. Amazingly, the eggs survive even when the soil dries out. When the eggs in soil once again have consistent moisture, they hatch! One female mosquito may lay up to 200 eggs per batch . Standing water should be reduced as mush as possible to prevent mosquitoes from developing.

You should protect yourself by using an insect repellant (following all label instructions) with any of these active ingredients or using one of the other strategies:

- DEET

- Picaridin

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus

- Para-menthane diol

- IR3535

- An alternative is to wear long-sleeved shirts and pants – although that’s tough in our hot weather

- Wear clothing that is pre-treated with permethrin or apply a permethrin product to your clothes, but not your skin!

- Avoid getting bitten while you sleep by choosing a place with air conditioning or screens on windows and doors or sleep under a mosquito bed net.

Now let’s talk about mosquito control in your own landscape.

Let’s first explore what kind of environment in your landscape and around your home is friendly to the proliferation of mosquitoes. Adult mosquitoes lay their eggs on or very near water that is still or stagnant. That is because the larvae live in the water but have to come to the surface regularly to breeze. The small delicate larvae need the water surface to be still in order to surface and breathe. Water that is continually moving or flowing inhibits mosquito populations.

Look around your home and landscape for these possible sites of still water that can be excellent mosquito breeding grounds:

- bird baths

- potted plant saucers

- pet dishes

- old tires

- ponds

- roof gutters

- tarps over boats or recreational vehicles

- rain barrels (screen mesh over the opening will prevent females from laying their eggs)

- bromeliads (they hold water in their central cup or leaf axils)

- any other structure that will hold even a small amount of water (I even had them on a heating mat in a greenhouse that had very shallow puddles of water!)

You may want to rid yourself of some of these sources of standing water or empty them every three to four days. What if you have bromeliads, a pond or some other standing water and you want to keep them and yet control mosquitoes? There is an environmentally responsible solution. Some bacteria, Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. israelensis or Bacillus sphaericus, only infects mosquitoes and other close relatives like gnats and blackflies and is harmless to all other organisms. Look for products on the market that contain this bacteria.

For more information:

Mosquito Repellents

UF/IFAS Mosquito Information Website

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 5, 2017

This rain garden used stone for a berm and muhly grass as a decorative and functional plant. Photo credit, Jerry Patee

Tropical Storm Cindy’s early arrival soaked northwest Florida this month, followed by even more heavy rain. Homes in low areas and along the rivers flooded and suffered extensive damage. That being said, we are just entering our summer “rainy season,” so it may be wise to spend extra time thinking about adjusting your landscape to handle our typically heavy annual rainfall.

For example, if you have an area in your yard where water always runs after a storm (even a mild one) and washes out your property, you may want to consider a rain garden for that spot. Rain gardens are designed to temporarily hold rainwater and allow it to soak into the ground. However, they are quite different aesthetically from stormwater ponds, because they are planted with water-tolerant trees, shrubs, groundcovers and flowers to provide an attractive alternative to the eroding gully that once inhabited the area! Rain gardens are not “created wetlands,” but landscaped beds that can handle both wet and drier conditions. Many of the plants best suited for rain gardens are also attractive to wildlife, adding another element of beauty to the landscape.

A perfect spot for a rain garden might be downhill from a rain gutter, an area notorious for excess water and erosion. To build a rain garden, the rainwater leaving a particular part of the property (or rooftop), is directed into a gently sloping, 4”-8” deep depression in the ground, the back and sides of which are supported by a berm of earth. The rain garden serves as a catch basin for the water and is usually shaped like a semi-circle. The width of the rain garden depends on the slope and particular site conditions in each yard. Within the area, native plants are placed into loose, sandy soil and mulched. Care should be taken to prevent the garden from having a very deep end where water pools, rather allowing water to spread evenly throughout the basin.

This larger rain garden, or bioretention area, functions as stormwater treatment for a large parking lot in North Carolina. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF / IFAS Extension

Besides reducing a problematic area of the lawn, a rain garden can play an important role in improving water quality. With increasing populations come more pavement, roads, and rooftops, which do almost nothing to absorb or treat stormwater, contributing to the problem. Vegetation and soil do a much better job at handling stormwater. Excess sediment, which can fill in streams and bays, and chemicals from fertilizers and pesticides are just some of the pollutants treated within a rain garden via the natural growth processes of the plants.

A handful of well-known plants that work great in rain gardens include: Louisiana iris, cinnamon fern, buttonbush, Virginia willow, black-eyed Susan, swamp lily, tulip poplar, oakleaf hydrangea, wax myrtle, Florida azalea, river birch, holly, and Southern magnolia. For a complete list of rain garden plants appropriate for our area, visit the “Rain Garden” section of Tallahassee’s “Think about Personal Pollution” website.

For design specifications on building a rain garden, visit the UF Green Building site or contact your local UF IFAS County Extension office.

by Molly Jameson | May 11, 2017

If you are a farmer, you have most likely heard about the Food Safety Modernization Act, or FSMA, by now. If you are not a farmer, you probably do not know that food safety regulations are going through a big change. The FSMA, which was passed in 2011, is considered the largest update to food safety regulation in over 80 years.

The proposed produce safety rule under the FSMA is very robust, establishing the minimum standards for worker training, health and hygiene, agricultural water use, animal soil amendments, on-farm domesticated and wild animals, equipment, tools, buildings, and sprout production.

But this new rule will not apply to all farmers. The commodities they produce and the value of their produce sold will ultimately dictate whether they will need to comply.

First, the rule does not apply to produce that is not a raw agricultural commodity, or commodities the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has identified as “rarely consumed raw.” Secondly, if a farm has an average value of produce sold of $25,000 or less within the previous three years, they are also exempt.

If the farmer produces an agricultural commodity in which the rule applies and the value of their produce sold is over $25,000, it is still possible the farm will be exempt from most of the requirements.

Fresh cucumbers, for example, are considered a raw commodity. But cucumbers that will undergo further processing, such as for pickling, would be eligible for exemption from the produce rule. Photo by Molly Jameson.

For instance, if the average annual monetary value of food sold directly to qualified end-users was more than the average annual value of the food sold to all other buyers within the previous three-year period, the farmer would meet the first half of exemption eligibility.

What is a “qualified end-user”, you ask? They are considered the consumers of the food, or restaurant or retail food establishment, located with the same state as the farm that produced the food (or no more than 275 miles).

But even if farmers meet the above exemption eligibility standards, they must also meet the second requirement. That is, the average annual monetary value of all food sold during the three-year period must be less than $500,000, when adjusted for inflation.

If this all sounds confusing, you are not alone! This is why the FDA developed a chart to help farmers determine if they will be exempt: Standards for Produce Safety – Coverage and Exemptions/Exclusions for Proposed 21 PART 112.

Whether farms will be exempt from the FSMA produce safety rule or not, it is always a good idea to follow good agricultural practices and to have a farm food safety plan. To learn more about food safety on farms, view the EDIS document Food Safety on the Farm: An Overview of Good Agricultural Practices.

If you are a farmer, or know someone who would benefit from having a food safety plan, the UF Small Farms Academy Extension Agents are offering a Building Your Own Farm’s Food Safety Manual Workshop in Tallahassee to help growers develop their own food safety manuals.

The workshop is tailored to fresh fruit and vegetable farms, fields, or greenhouses and is partially supported by a grant through the Florida Specialty Crops Block Grant program from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Service.

The registration fee is $35 for the first person representing a farm and $15 for an additional attendee from that farm. The workshop is limited to 20 farms on a first come, first serve basis.

The workshop will take place at the Amtrak Station, County Community Room, 918 Railroad Ave, in Tallahassee, FL, on Tuesday, May 23, 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Register on Eventbrite by following this link: https://farmfoodsafetymanualworkshop.eventbrite.com

Please note, this class will help farmers develop their farm’s food safety manual, but it does not fulfill the new FDA FSMA one-time training requirement.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 6, 2015

Just over a year ago, southwest Alabama and northwest Florida experienced a devastating storm that left hundreds without access to their homes and businesses, flooded out and stranded by a hurricane-force storm that didn’t come with the luxury of a week’s warning. Rainfall records in Pensacola go back to 1879, and the April 29-30 storm broke them all, estimating just over 20 inches over the two days. Not only was the rainfall heavy, but the torrent was high in both velocity and volume—at one point, a mind-boggling 5.68 inches fell in the span of one hour. That’s half the annual rainfall of many cities in California and Texas!

A residential street in Pensacola became a raging river a year ago during the torrential floods, putting dozens of people out of their homes. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson UF/IFAS Extension.

With every dark storm cloud comes a silver lining, though, and just like the millions pumped into our regional economy from oil spill-related fines, the April 2014 floods have awakened a “greener” ethic among many residents, business owners, and politicians. According to a study just released by an environmental consulting firm, when asked about infrastructure changes and improvements to flooding and stormwater, attendees at community meetings overwhelmingly preferred “low impact” solutions such as expanded green space, cisterns, rain gardens, and stream restoration to “hard” structures such as bigger underground pipes and more pumps. While traditional engineering infrastructure is still crucial to a community that must maintain roads, stormwater ponds, and buildings, I find it encouraging that residents are interested in trying different techniques that have proven successful both here and in other parts of the world.

The new Langley Bell 4-H Center has four large rain barrels around the building, used to collect roof runoff for landscape design. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson UF/IFAS Extension.

So, how does one prepare for unexpected rain and floods? The first thing is to realize that northwest Florida receives the most annual rainfall (over 60”) of any region of the state, and sometimes it seems to come down all at once. Preparing landscapes to handle both frequent and heavy rains is an important place to start. This article will begin a series of articles delving into those “low-impact” stormwater management techniques that can help lessen the impact of the intense storms we experience here in northwest Florida. Many of these practices, such as creating mulch pathways, harvesting rainwater, and installing shoreline vegetative buffers, can be implemented by individual homeowners and help reduce the impact of flooding on a neighborhood and city-wide level