by Laura Tiu | May 12, 2018

Are you interested in learning about marine life, going fishing, or exploring the underwater world with a mask and snorkel? If so, this is the camp for you! This local education opportunity for budding marine scientists will be happening this summer at Camp Timpoochee in Niceville, FL. The camps enable participants to explore the marine and aquatic ecosystems of Northwest Florida; especially that of the Choctawhatchee Bay. Campers get to experience Florida’s marine environment through fishing, boating snorkeling, games, STEM (science, technology, engineering & math) activities and other outdoor adventures. University of Florida Sea Grant Marine Agents and State 4-H Staff partner to provide hands-on activities exploring and understanding the coastal environment.

Sampling the benthic community at Timpoochee.

Florida Sea Grant has a long history of supporting environmental education for youth and adults to help them become better stewards of the coastal zone. This is accomplished by providing awareness of how our actions affect the health of our watersheds, oceans and coasts and marine camp is a great opportunity for sharing that information. Many of the Sea Grant youth activities use curriculum developed by the national Sea Grant program and geared toward increasing student competency in math, science, chemistry and biology. The curriculum is fun and interesting!

Marine Camp is open to 4-H members and non 4-H members between the ages of 8-13 (Junior Camp) and, new this year, ages 14-17 (Senior Camp). There will be two Junior Camps in 2018. The July 23-27 camp is full, but there are still openings for the June 25-29 session. The cost for Junior Marine Camp is $275.00 for the week. A more intensive Senior Marine Camp has been scheduled for July 16-20. This camp will contain a community service component and costs $300 for the week.

If Marine Camp sounds interesting to someone you know, visit the Camp Timpoochee website at http://florida4h.org/camps_/specialty-camps/marine/ for the 2018 dates and registration instructions. A daily snack from the canteen and a summer camp T-shirt are included in the camp fees, along with three nutritious meals per day prepared on site by our certified food safety staff. All cabins are air-conditioned. So many surprises await at marine camp, come join the fun.

Seining the sea grass at Timpoochee.

Larval fish in the Timpoochee oyster reef.

by Rick O'Connor | May 12, 2018

Records of the variety of aquatic life in Pensacola Bay go back to the 18th century. According to these reports, over 1400 species of plants and animals call Pensacola Bay home. Many of them depend on seagrass, oyster reefs, or marshes to complete their life cycle. The greatest diversity and abundance are found on the oyster reefs. Finfish and shellfish in the bay have sustained humans as a food source for centuries. However, we know that the alligator, turtles, and a variety of birds and mammals have also been important. In this article, we will focus on the aquatic species.

Red Drum – photo credit Florida Fish and Wildlife

When people think of aquatic life in the bay, they first think of fish. About 200 species call Pensacola Bay home. The most abundant are the true estuarine fish, such as croakers, sardines, and minnows. There are a variety of marine transient fish that can be found such as jacks, mackerels, and some species of sharks. Spot and Atlantic Croaker are the most abundant members of the croaker family, and are still an important target fish for locals. Anyone who has snorkeled or cast a line with cut bait knows how common pinfish can be, and those who have pulled bait nets are very familiar with the silverside minnows and anchovies.

I have pulled many a seine net over the years assessing the diversity and abundance of the nearshore fish populations and logged 101 species. In addition to those listed above, killifish (also locally known as “bull minnows”) are a common capture. For a few years, we were involved in trawling in deeper waters where we collected a variety of flounder, silver perch, grunts and snapper. Sea robins are an interesting member of our community and gag grouper were captured occasionally. The number and variety of fish found varies with seasons and is greatest in June. The diversity and abundance of estuarine fishes in our bay is very similar to neighboring estuaries.

The second thing people think of when they think of aquatic life in the bay are shellfish. These would include the crabs, shrimp, and oysters. However, the most abundant macro-invertebrates in our bay are those that can tolerate environmental stress and live in the surface layers of the sediments – these are the worms and crustaceans. There are numerous varieties of segmented polychaete worms, who are famous for building tunnels with “volcano” openings. They are also common within oyster reefs, feeding on all sorts of organic debris. Blue crab are common throughout the bay and provided both a commercial and recreational fishery for years. Brown and white shrimp are both found and have been the most popular seafood with locals for years.

The famous blue crab.

Photo: FWC

During my lifetime, the only marine mammal commonly seen has been the Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin, and these are found in many parts of the bay. Years back, I heard accounts of harbor porpoise, but never actually saw one. An historic occurring marine mammal, who seems to be making a comeback, is the Florida Manatee. Sightings of this animal have been reported in a variety of locations in recent years.

Snakes, turtles, and alligators are all found in the bay area. There is really only one saline snake and this is the gulf coast salt marsh snake. However, nontraditional estuarine snakes, such as the cottonmouth, are becoming more common in and near the bay. Though we have a great variety of turtles in our rivers, only one true estuarine turtle exist in the country, the diamondback terrapin – and this turtle can be found in parts of our bay. Sea turtles do venture into the bay searching for food, particularly the green turtle who is fond of seagrasses.

Many forget the small planktonic animals that drift in the water column, but they are there – about 100 species of them. Copepods are small roach looking crustaceans that are by far the most abundant member of the zooplankton, particularly the species known as Acartia tonsa – which makes up 82% of the abundance in our bay. These small animals are an important link in the food chain of almost every other member of the bay community. The zooplankton variety in Pensacola Bay is very similar to those of neighboring estuaries.

And then there are the plants…

By far, the most diverse group of organisms in the bay are the microscopic plants known as phytoplankton – with over 400 species reported. Much of the bay is too deep to support traditional forms of plants and so these become a key producer of food for many species. The diversity and abundance is greatest in the spring and fall. 70% of the phytoplankton are from a group called dinoflagellates, small plants that have two hair-like flagella to orient, and even propel, themselves. Some of them produce the bioluminescence we sometimes see and others produce what we call red tide. During the summer, the populations change and the more abundant forms are diatoms. These lack the flagella of the dinoflagellates, but they do produce beautiful shells of silica.

There are at least 400 species of periphytic algae (attaching). Green algae are the most abundant and are most common in the local bayous. Cyanobacteria, which were once thought to be algae, are the most abundant in the marshes and periphytic diatoms dominate in the Sound.

And last, are the submergent and emergent grasses.

Submergent grasses are known as seagrasses. We have three species that like the higher saline waters. These are turtle, shoal, and widgeon grass. Turtle and shoal grass need the water to be at least 25 parts per thousand and are the dominate species in the lower portions of the bay. Widgeon grass can tolerate waters as low as 10 ppt and are found in the bayous and the upper portions of the bay system. Tapegrass only survives in freshwater and are found in the lower reaches of the rivers where they meet the bay.

Emergent grasses are what we call marsh grasses. Two species, Black Needlerush and Smooth Cordgrass dominate these. There are pockets of salt marshes found all over the bay system.

So how is the health of our aquatic life?

As you might expect, the diversity and abundance have declined over time, particularly since the 1950’s. One firsthand account of the change, describe a bayou that was clear, full of grass, and harbored shrimp the size of your hand. Then they were gone. He remembered the first change being water clarity. As development along our waterfront increased, the clarity decreased and the aquatic life declined. This has happened all over the bay system. Increase in run-off not only brought sand and sediment lowering water clarity, it also brought chemicals that both the plants and animals could not tolerate. Much of the point source pollution has been controlled but non-point pollution is still problematic. Fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, oils and grease, and sediment have all been problematic. These can be reduced. Following recommendations from the Florida Friendly Landscaping website, (http://www.floridayards.org/.) property owners can alter how they are currently managing their landscape to reduce their impact on the aquatic life on the bay. Clean Marina (https://floridadep.gov/fco/clean-marina ) and Clean Boater (https://floridadep.gov/fco/cva/content/clean-boater-program ) recommendations can help reduce the impact from the boating community. Sustainable fishing practices, such as safe catch and release methods for unwanted fish and removing all monofilament are good practices. In 2019, Sea Grant will begin a program training local citizens how to monitor the diversity and abundance of aquatic species. If interested in volunteering, stay tuned.

Reference

Lewis, M.J., J.T. Kirschenfeld, T. Goodhart. 2016. Environmental Quality of the Pensacola Bay System: Retrospective Review for Future Resource Management and Rehabilitation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Gulf Breeze FL. EPA/600/R-16/169.

by Ray Bodrey | May 7, 2018

It’s a struggle to manage our Panhandle landscapes, especially over the late spring-summer months. Just remember, small adjustments can mean significant impacts in conserving water.

Some homeowners are not aware that watering plants too much can have as much of an ill effect as not watering enough. Shallow rooted plants, as well as newly set plants can easily become water stressed. Some people lightly water their plants each day. With this practice, one is only watering an inch or less of the topsoil. Most plant roots are deeper than this. Instead of a light watering every day, soaking the plant a few times a week is best. A soil that has been soaked will retain moisture for several days. This is a very good practice for young plants. In contrast, some people soak their plants to often. This essential drowns the roots by eliminating vital oxygen in the root zone. This can also cause root rot. Signs of overwatering are where leaves turn brown at the tips or edges, as well as leaf drop.

Figure 1: Rain Barrel.

Credit: UF/IFAS Florida-Friendly Landscaping.

The following are tips from the UF/IFAS Florida-Friendly Landscape Program. These tips will help you conserve water and provides best management practices for your landscape.

- Choose the right plant for the right place: Be sure to place plants in your landscape that match conditions with plant needs.

- Water Thoughtfully: Of course, follow water restrictions first and foremost. Water early in the morning and water when plants and turfgrass start to wilt. Refrain from watering in the late afternoon or evening. This is when insects and diseases are most active.

- Perform regular irrigation maintenance: Remember, an irrigation system is only effective if it is maintained regularly. Check for and repair leaks. If using a pop-up heads for turfgrass, point heads away from driveways and sidewalks.

- Calibrate turfgrass irrigation system: Ideal amount of water to apply to turfgrass is ½”- ¾”. A simple test can be done to calibrate. Place a coffee or tuna cans throughout the landscape. Run the irrigation system for 30 minutes. Average the depth of the water containers. Adjust running time to apply the ½”- ¾” rate.

- Use microirrigation in gardens and individual plants: Drip or microspray irrigation systems apply water directly to the root system with limited surface evaporation.

- Make a rain barrel: Rain barrels are an inexpensive way to capture rainwater from your roof. This can translate into a big impact on your water bill as well.

- Mulch plants: Mulch helps keep moisture in the root zone. Two to three inches in depth, for a few feet in diameter will work well for trees, shrubs, flowers and vegetables.

- Mow correctly: Mowing your grass at the highest recommended length is key. Be sure to cut no more than 1/3 of the leaf blade each time you mow. Keep mowing blades sharp as dull cuts often cause grass to be prone to disease.

- Be a weather watcher: Wait at least 24 hours after a rainfall event to water. If rain is in the forecast, wait 48 hours until irrigating. Use a rain gauge or install a rain shut-off device to monitor irrigation scheduling.

Following these tips will help you conserve water and maximize watering efforts in your landscape. For more information on water conservation principles please contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information can be found at the UF/IFAS Center for Landscape Conservation & Ecology’s Drought Toolkit: http://clce.ifas.ufl.edu/drought_toolkit/

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Rick O'Connor | May 4, 2018

Humans have inhabited the shores of Pensacola Bay for centuries. Impacts on the ecology have happened all along, but the major impacts have occurred in the latter half of the 20th century. There has been an increase in human population, an increase in development, a decrease in water clarity, a decrease in seagrasses, and a decrease in the abundance of some marine organisms – like horseshoe crabs, scallops, and some marine fishes. There has also been an increase in inorganic and organic compounds from stormwater run-off, fish kills, and health advisories due excessive nutrients and fecal bacteria in local waters.

A view of Pensacola Bay from Santa Rosa Island.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Since the 1970’s, there have been efforts to help restore the health of the bay. Seagrasses have returned in some areas, fish kills have significantly reduced, and occasionally residents find scallops and horseshoe crabs – but there is still more to do. In this series of articles, I will present information provided in a recent publication (Lewis, et. al. 2016) and from citizen science monitoring. We will begin with an introduction to the bay itself.

The Pensacola Bay System is the fourth largest estuarine system in the state of Florida. The system includes Blackwater, Escambia, East, and Pensacola Bays. There are numerous smaller bayous, such as Indian, Mulat, and Hoffman, and three larger ones, which include Texar, Chico, and Grande. There are two lagoons that extend east and west of the pass. To the west is Big Lagoon and to the east is Santa Rosa Sound. The surface area of this bay system is about 144 mi2 and the coastline runs about 552 miles in length. There are four rivers that discharge into the system: the Escambia, Blackwater, Yellow, and East Rivers. The majority of watershed is in Alabama and covers about 7000 mi2. The mouth of the bay is located at the Pensacola Pass near Ft. Pickens and is 0.5 miles across. Depending on the source, the flush time for the entire bay has been reported between 18 and 200 days.

There are several ecosystems found within the bay system. Seagrasses are be found throughout the bay and bayous, but are more prevalent in Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Oyster reefs have provided income for some in the East Bay area in the past, but production has declined in the last 50 years. Salt marshes are found throughout the bay as well, but the greatest acreage is in the Garcon area of Santa Rosa County. There are, of course, freshwater marshes near the mouths of the rivers with the largest being at the mouth of the Escambia River.

Members of the herring family are ones who are most often found during a fish kill triggered by hypoxia.

Photo: Madeline

Members of the drum family are one of the more common fishes found in the system and would include fish like the Spot and Atlantic Croaker. However, speckled trout, striped mullet, redfish, several species of flounder, have also been targets for local fishermen. Target fish include sardines, silversides, stingrays, pinfish, and killifish. Brown shrimp, oysters, and blue crab have historically provided a fishery for locals, but other invertebrates include several species of jellyfish, stone crabs, fiddler crabs, hermit crabs, grass shrimp, several species of snails, clams, bay squid, octopus, and even starfish. There is also a variety of benthic worms found within the sediments.

A finger of a salt marsh on Santa Rosa Island. The water here is saline, particularly during high tide. Photo: Rick O’Connor

There has been a decline in overall environmental quality since 1900 but, again, the biggest impacts have been between 1950 and 1970. Fish kills, a reduction in shrimp harvest, and hypoxia (a lack of dissolved oxygen) have all been problems.

In the articles to follow we will look deeper into specific environmental topics concerning the health of Pensacola Bay.

References

Lewis, M.J., J.T. Kirschenfeld, T. Goodhart. 2016. Environmental Quality of the Pensacola Bay System: Retrospective Review for Future Resource Management and Rehabilitation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Gulf Breeze FL. EPA/600/R-16/169.

by Andrea Albertin | May 4, 2018

Special care needs to be taken with a septic system after a flood or heavy rains. Photo credit: Flooding in Deltona, FL after Hurricane Irma. P. Lynch/FEMA

Approximately 30% of Florida’s population relies on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater. This includes all water from bathrooms and kitchens, and laundry machines.

When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low. In a nutshell, the most important things you can do to maintain your system is to make sure nothing but toilet paper is flushed down toilets, reduce the amount of oils and fats that go down your kitchen sink, and have the system pumped every 3-5 years, depending on the size of your tank and number of people in your household.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

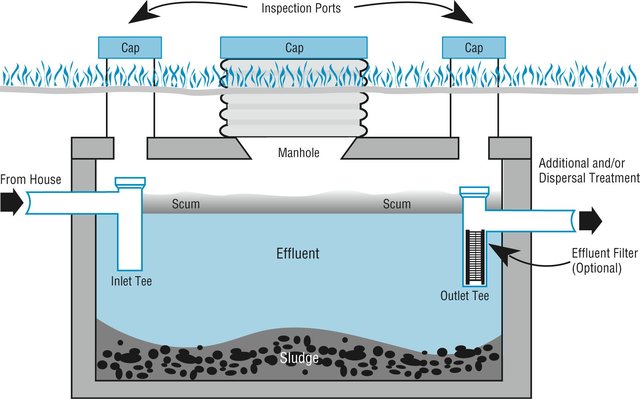

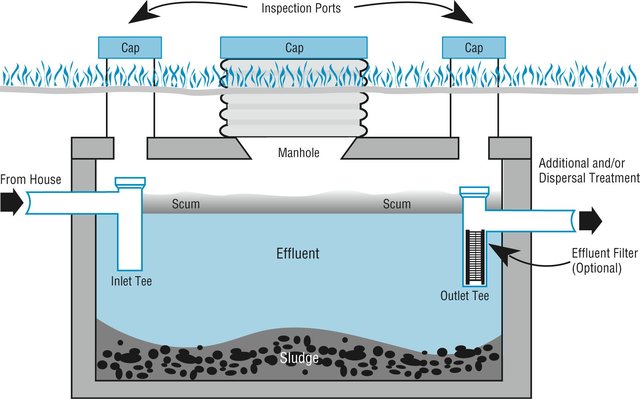

Image credit: wfeiden CC by SA 2.0

How does a traditional septic system work?

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, made up of (1) a septic tank (above), which is a watertight container buried in the ground and (2) a drain field, or leach field. The effluent (liquid wastewater) from the tank flows into the drain field, which is usually a series of buried perforated pipes. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. Bacteria break down the solids (the organic matter) in the tank. The effluent, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out of the tank and into the drain field where it then percolates down through the ground.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

What should you do after flooding occurs?

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. For your septic system to work properly, water needs to drain freely in the drain field. Under flooded conditions, water can’t drain properly and can back up in your system. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drain field while the soil is water logged. Don’t drive heavy vehicles or equipment over the drain field. By using heavy equipment or working under water-logged conditions, you can compact the soil in your drain field, and water won’t be able to drain properly.

- Don’t open or pump out the septic tank if the soil is still saturated. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened, and can end up in the drain field, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can also cause a tank to pop out of the ground.

- If you suspect your system has been damage, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drain field remains soggy and never fully drains, and/or a foul odor persists around the tank and drain field.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drain field. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain into your septic drain field – this adds an additional source of water that the drain field has to manage.

More information on septic system maintenance after flooding can be found on the EPA website publication https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/septic-systems-what-do-after-flood

By taking special care with your septic system after flooding, you can contribute to the health of your household, community and environment.