by Ray Bodrey | Jul 11, 2022

The University of Florida/IFAS Extension faculty are reintroducing their acclaimed “Panhandle Outdoors LIVE!” series. Conservation lands and aquatic systems have vulnerabilities and face future threats to their ecological integrity. Come learn about the important role of these ecosystems.

The St. Joseph Bay and Buffer Preserve Ecosystems are home to some of the one richest concentrations of flora and fauna along the Northern Gulf Coast. This area supports an amazing diversity of fish, aquatic invertebrates, turtles, salt marshes and pine flatwoods uplands.

This one-day educational adventure is based at the St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve near the coastal town of Port. St. Joe, Florida. It includes field tours of the unique coastal uplands and shoreline as well as presentations by area Extension Agents.

Details:

Registration fee is $45.

Meals: breakfast, lunch, drinks & snacks provided (you may bring your own)

Attire: outdoor wear, water shoes, bug spray and sun screen

*if afternoon rain is in forecast, outdoor activities may be switched to the morning schedule

Space is limited! Register now! See below.

Tentative schedule:

All Times Eastern

8:00 – 8:30 am Welcome! Breakfast & Overview with Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension

8:30 – 9:35 am Diamondback Terrapin Ecology, with Rick O’Connor, Escambia County Extension

9:35 – 9:45 am Q&A

9:45- 10:20 am The Bay Scallop & Habitat, with Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension

10:20 – 10:30 am Q&A

10:30 – 10:45 am Break

10:45 – 11:20 am The Hard Structures: Artificial Reefs & Marine Debris, with Scott Jackson, Bay County Extension

11:20 – 11:30 am Q&A

11:30 – 12:05 am The Apalachicola Oyster, Then, Now and What’s Next, with Erik Lovestrand, Franklin County Extension

12:05 – 12:15 pm Q&A

12:15 – 1:00 pm Lunch

1:00 – 2:30 pm Tram Tour of the Buffer Preserve (St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve Staff)

2:30 – 2:40 pm Break

2:40 – 3:20 pm A Walk Among the Black Mangroves (All Extension Agents)

3:20 – 3:30 pm Wrap Up

To attend, you must register for the event at this site:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/panhandle-outdoors-live-at-st-joseph-bay-tickets-404236802157

For more information please contact Ray Bodrey at 850-639-3200 or rbodrey@ufl.edu

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 1, 2022

In December of 2021 the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) passed new regulations concerning the diamondback terrapin. One will make it illegal to possess a terrapin without a permit beginning March 1, 2022. The other will impact recreational crab trap design in early 2023. A number of people have begun to ask questions ab

The diamond in the marsh. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

ut this new ruling so, we will explain it.

WHAT IS A DIAMONDBACK TERRAPIN?

We will start there. Most Floridians have never heard of this animal, and if they have, they know it from the Chesapeake Bay area. Diamondback terrapins are turtles in the Family Emydidae. This family includes many of the pond turtles Floridians are familiar with – cooters, sliders, red-belly, and others. The big difference between terrapins and pond turtles is the coloration of their skin, and their preference for brackish water – they like estuaries over ponds and lakes. They do have lachrymal glands in their eyes to help excrete salt from water, but they are not as efficient as those of sea turtles so, they cannot live in sea water for more than about a month – it is the bays and bayous they like to call home.

There are seven recognized subspecies which range from Cape Cod MA., to Brownsville TX. Five of them are found in Florida and three are only found in Florida. But few Floridians have ever heard of them and even fewer have seen one. Their cousins the pond turtles are quite common. We see their heads in ponds and lakes, several of them basking on logs near shore of ponds, lakes, and rivers, and frequently see dead ones along our highways. We don’t see terrapins. We do not see their heads in the marsh, basking on logs, or dead carcasses along our coastal highways. Again, this is an unknown turtle to us.

WHY ARE THERE NEW REGULATIONS ON A TURTLE MANY HAVE NEVER SEEN?

The question sort of explains the answer – we do not see them – their population in our state may deem some action by the FWC. In the Chesapeake region they are quite common, and people see them frequently. It is the mascot of the University of Maryland. Along the roads to the barrier islands in Georgia hundreds of terrapins can be found trying to nest and many are hit by cars. In most of these mid-Atlantic states there is some form of protection for them. They either list them as threatened or a species of concern. One state has it listed as endangered. Again, these are states where encounters are much more common.

Florida has a rich diversity of turtles, maybe the richest in the country, and we have been the target for turtle harvest. Turtles are sought after for food and as pets. The harvest of some species has been heavy and FWC has listed them as “no take”. For a variety of reasons, harvest being one of them, Alligator Snapping Turtles (Macrochelys temminckii), the Suwannee Cooter (Pseudemys suwanniensis), and the Barbour’s Map Turtle (Graptemys barbouri) are illegal to possess without a permit. This includes their eggs. Because other species look very similar to these, they have also been added to the no-take list. This would include all species of cooters and snapping turtles, the Escambia Map Turtle (Graptemys ernsti) and the Striped Mud Turtle (Kinosternon baurii) – which is a small riverine turtle that resembles a small snapping turtle. Note: the regulation on the striped mud turtle is for the lower Florida Keys only. You could take diamondback terrapins but only one and you could have no more than two in your possession. You could not possess their eggs. But with the 2021 ruling – this has changed.

As mentioned, terrapin encounters are rare in our state. There has been concern about their population status here. I got involved with them in 2005 primarily to answer the question “Do terrapins even exist in the Florida panhandle?”. The answer is yes, they do. Since 2005 myself, and trained volunteers, have conducted 859 surveys searching for them between Escambia and Franklin counties. We have encountered terrapins, or terrapin sign (tracks, shells, depredated nests) 215 of those – 25% of the surveys; most of those encounters were terrapin sign – they are hard creatures to find. Because of the low encounter rate across the state, it is believed that the populations here are low and in need for conservation measures.

Then comes the crab traps…

Researchers with the Diamondback Terrapin Working Group have identified several stressors to terrapin populations. Loss of habitat, depredated nests by predators (particularly the raccoon), road mortality, and… crab traps. Terrapins feed primarily on shellfish but will eat other things if given the opportunity. They do have a tendency to enter crab traps. Though they feed on small juvenile crabs it is the bait we think they are after in this scenario. Once in, like blue crabs, they find it hard to escape. Unlike blue crabs, turtles have lungs, and the terrapins eventually drown. In the Chesapeake Bay region blue crabs are ”king” – a major commercial and recreational fishery. Terrapins entering crab traps means crabs are not. There have been as many as 40 dead terrapins found in one trap. This was a major concern for all. Dr. Roger Woods of the Wetlands Institute in New Jersey began working on a device that would keep terrapins out but allow blue crabs in. Data shows that in most cases, the larger females are the ones entering and the smaller males would follow. If you could keep the female out it was believed that most males would not enter. So, the device was designed to keep the large females out. A 6×2” rectangle seemed to work best. Field studies showed that these By-Catch Reduction Devices (BRDs) kept 80-90% of the terrapins out and did not significantly impact the crab catch. We had a design that seemed to work.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

BRDs are designed to keep terrapins out but allow crabs to enter.

Photo: Virginia Sea Grant

These BRDs have been required in the Mid-Atlantic states for a few years now. With the concern in Florida populations, it is now coming to Florida. By March 1, 2023, all recreational crab traps in Florida will be required to have a fixed funnel size no larger than 6×2”. Either the funnel must be this size, or you can attach one of the plastic orange BRDs to the opening (see photo). Currently bait and tackle shops do not have the BRDs but will be acquiring over the next year. FWC will be working on providing sources between now and March of 2023. If you are in the Pensacola area you can contact me, I have a case of them in my office.

As far as having one on your possession – it is now a no-take species. This rule began March 1, 2022. If you have had a terrapin in your possession you can apply for a no-cost permit to keep it (visit the FWC link below to obtain information on applying for this permit). If you are an education facility that houses terrapins for educational purposes – the same, you can apply for a no-cost education permit to keep your terrapins. You must have this permit by May 31, 2022.

If you have any questions concerning this ruling or how to comply with it, you can contact FWC or your county Sea Grant Extension Agent. The FWC link for more information on this, and other turtle regulations, can be found at https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/freshwater-turtles/?redirect=freshwaterturtles&utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_name=&utm_source=govdelivery&utm_term=campaign.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 11, 2022

Let’s begin by stating what a diamondback terrapin is. I have found many Floridians are not familiar with the animal. It is a turtle. A turtle in the family Emydidae which includes the pond turtles, such as cooters and sliders. The big difference between terrapins and the other emydid turtles is their preference for salt water. They are not marine turtles but rather estuarine – they like brackish water.

The diamond in the marsh. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Their haunt are the salt marshes and mangroves of the state. Their range extends from Massachusetts down the east coast and covering all of the Gulf of Mexico over to Brownsville Texas. There are seven subspecies of the animal within that range. Five of those live in Florida and three only live in Florida. They are more abundant, and well known, in the Chesapeake Bay area where they are the mascot of the University of Maryland. In Florida they seem to be more secretive and hidden. Encounters with them are rare and there has been concern about their status for years. Though researchers are not 100% sure on their population size, it was felt that more conservation measures were needed.

Ten years ago, the issue with all turtles in the state was the illegal harvest for the food trade. All sorts of species were being captured and sent to markets overseas. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) stepped in and set possession quotas on many species of Florida turtles. For terrapins, the number was two. For some, like the Suwannee Cooter, there was a no possession rule.

Drowned terrapins in a derelict crab trap in the Florida panhandle. (photo: Molly O’Connor)

There has also been concern with incidental capture of terrapins in crab traps. These turtles have been known to swim into the traps and drown. In the Chesapeake Bay area, they have found as many as 40 dead turtles in one trap. Not only is this bad for the turtles, but it is also bad for the crab fisherman because high numbers of dead turtles in the trap means no crabs. Studies began to develop some sort of excluder device that would keep terrapins out, but allow crabs in. Dr. Roger Wood developed a rectangle shaped wire excluder now called a By-Catch Reduction Device (BRD) that reduced the terrapin capture by 80-90% but had no significant effect on the crab catch. That was what they were looking for. This BRD has been required on crab traps up there for years.

What about Florida?

Studies using the BRD were also conducted here with the same results, but the BRD was not required. Incidental capture in crab traps does occur here but not to the extent it was happening in the Chesapeake and FWC wanted to hold off for more science before enacting the rule. BRDs were available for those who wanted them, but not required. This past December (2021) that changed.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

In recent years there has been another issue with harvesting terrapins for the pet trade. With this, and other conservation concerns for this turtle, FWC developed a new rule for terrapins at their December 2021 meeting.

- The possession limit for terrapins has dropped from 2 to 0 – there is a no-take rule for this animal beginning March 1, 2022. Collection for scientific research will still be allowed with a valid collecting permit from the FWC. Those who currently have two or less terrapins in their possession as pets may keep them but must obtain a no cost personal possession permit to do so by May 31, 2022. Those who have terrapins within an education center may keep them but must obtain a no cost exhibit permit by May 31, 2022.

- Recreational crab traps will require the BRD device by March 1, 2023. You have a year. Those in the Pensacola area can contact me for these. I have a case of them I am willing to provide to the public.

Again, studies have shown that these BRDs do not significantly impact the crab catch. Crabs can turn sideways and still enter the traps. But reducing incidental capture of terrapins will hopefully increase their numbers in our state. For information on how to obtain the needed permits visit FWC.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 27, 2021

For those who lived in the Pensacola Bay area 50 or so years ago, this question comes up from time to time. By scallop I am speaking of the bay scallop (Argopecten irradians), the one sought by so many scallopers then and now. This relatively small bivalve sits on beds of turtle grass, gazing with their ice blue eyes, filtering the water for plankton and avoiding numerous predators. They only live for a year, maybe two. They aggregate in relatively large groups and mass spawn. Releasing male gametes first, then female, fertilizing externally in the water column, to create the next generation.

Bay Scallop Argopecten iradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

These are unique bivalves in that they can swim… sort of. When conditions are not good, or a predator is detected, they can use their single adductor muscle to open and close the shells creating a current of expelling water that “pushes” them along and off the bottom. They were once found from Pensacola to Miami… but no longer. Scallops have become almost nondetectable in much of their historic range. Today they congregate in the Big Bend area of the state, and there they are heavily harvested.

What happened?

Well, if you look at the variety of causes for species decline around the globe habitat loss is usually at the top of the list. The habitat of the bay scallop are seagrass beds. There are many publications reporting the loss of seagrasses across the Gulf and Atlantic coast. Locally we know that the historic beds of the Pensacola Bay system have declined. We also know that some of those beds have shown some recovery in the last 20 years. But was the loss enough to cause the decline of the scallop?

Studies show that there is a strong association between seagrasses and scallops. The planktonic larva typically attached to grass blades a week or two after fertilization. This seems essential to reduce predation. Once they drop from the blades, vegetative cover is important for their survival. This suggests yes – any loss of seagrass could begin the loss of bay scallops.

What about water quality?

We do know that scallops need more saline brackish water – at (or above) 20 parts per thousand (20‰); 10‰ or less is lethal. Sea Grant is currently working with citizen scientists in Escambia County to monitor the salinity of area waters weekly. Though we do not believe the data is usable until we have 100 readings from each location, early numbers suggest that locations in Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound are at 20‰ threshold. We do not know whether run-off engineering of the 1970s may have lowered the salinity to cause a die-off, and one would think (since they can swim) they would move to a better location. However, if salinities were low across much of their local range, and seagrasses were not available in areas where salinities were good, this could have a devasting impact on their numbers.

Then there is sedimentation. Studies show that young scallops (<20mm) that do not have seagrass to attach to settle on silty bottoms and their survival is very low. And then there are toxic metals, and other contaminants that scallops may have little tolerance for. It is known that juvenile scallops have a low tolerance for mercury.

Disease?

One study from the Tampa Bay area indicated that there was little loss of scallops due to disease and parasites.

And then there is overharvesting…

Scallops are mass spawners and there needs to be high numbers of adults near each other for reproduction to be successful. If people are taking too many, this can lead to more spaced adults and less chance of successful fertilization. This combined with environmental stressors probably did our populations in.

According to a publication from Sarasota Bay Estuary Program in 2010, populations of less than five scallops / 600m2 is considered collapsed. Sea Grant has been conducting volunteer scallop searches in the Pensacola Bay area for the last five years. In that time, we have found only one live scallop… we have collapsed. During the 2021 Scallop Search, 17 volunteers surveyed 4000m2 and found no live scallops. However, reports of live scallops outside of our surveys indicate they are still there. We will see what the future holds.

References

Castagna, Michael, Culture of the Bay Scallop, Argopecten irradians, in Virginia (1975). Marine Fisheries

Review, 37(1), 19-24.

https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/1200

Leverone, J.R. 1993. Environmental Requirements Assessment of the Bay Scallop

Argopecten Irradians Concentricus. Final Report. Tampa Bay Estuary Program. Pp.82.

Leverone, J.R., S.P. Geiger, S.P. Stephenson, and W.S. Arnold. 2010. Increase in Bay Scallop (Argopecten irradians) Populations Following Releases of Competent Larvae in Two West Florida Estuaries. Journal of Shellfish Research. Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 395-406.

by Ray Bodrey | Apr 20, 2021

Scott Jackson, UF/IFAS Extension Bay County & Florida Sea Grant

Ray Bodrey, UF/IFAS Extension Gulf County & Florida Sea Grant

Erik Lovestrand, UF/IFAS Extension Franklin County & Florida Sea Grant

Can you remember where you were one year ago last April? The uncertainty of each day seemed to go on forever. At this time last year, we were planning several education programs that eventually had to be canceled or migrated to online events. Scallop Sitters was one of our cooperative volunteer programs with Florida Fish and Wildlife (FWC) that was postponed during the pandemic in 2020. Thankfully, FWC biologists continued restoration work last year in the region with good results and steps forward. However, there was something painfully absent in these efforts – you!

One of the lessons last year taught us, is to appreciate our opportunities – whether it is to be with your family, friends, or serve your community freely through volunteer service. Some new service opportunities appeared while others were placed on hold. Thankfully, we are excited to announce the Scallop Sitters Citizen Scientist Restoration Program is returning to our area in St. Andrew, St. Joe, and Apalachicola Bays this summer!

Historically, populations of bay scallops were in large numbers and able to support fisheries across many North Florida bays, including St Andrew Bay. Consecutive years of poor environmental conditions, habitat loss, and general “bad luck” resulted in poor annual scallop production and caused the scallop fishery to close. Bay scallops are a short-lived species growing from babies to spawning adults and dying in about a year. Populations can recover quickly when growing conditions are good and can be decimated when conditions are bad.

An opportunity to jump start restoration of North Florida’s bay scallops came in 2011. Using funding as a result of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, a multi-county scallop restoration program was proposed and eventually established in 2016. Scientists with FWC use hatchery reared scallops obtained from parents or broodstock from local bays to grow them in mass to help increase the number of spawning adults near critical seagrass habitat.

FWC also created another program where volunteers can help with restoration called “Scallop Sitters” in 2018 and invited UF/IFAS Extension to help manage the volunteer portion of the program in 2019 which led to targeted efforts in Gulf and Bay Counties.

After a year’s hiatus, UF/IFAS Extension is partnering with FWC again in Bay and Gulf Counties and expanding the program into Franklin County. Despite initial challenges with rainfall, stormwater runoff, and low salinity, our Scallop Sitter volunteers have provided valuable information to researchers and restoration efforts, especially in these beginning years of the program.

Volunteers manage predator exclusion cages of scallops, which are either placed in the bay or by a dock. The cages provide a safe environment for the scallops to live and reproduce, and in turn repopulate the bays. Volunteers make monthly visits from June until January to their assigned cages where they clean scallops removing attached barnacles and other potential problem organisms. Scallop Sitters monitor the mortality rate and collect salinity data which determines restoration goals and success in targeted areas.

You are invited! Become a Scallop Sitter

1.Register on Eventbrite

2.Take the Pre-Survey (link will be sent to your email address upon Eventbrite Registration)

3.View a Virtual Workshop in May

4.Attend a Zoom virtual Q & A session in May or June with multiple dates / times available

5.Pick up supplies & scallops on June 17 with an alternate pick-up date to be announced

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Erik Lovestrand | Mar 11, 2021

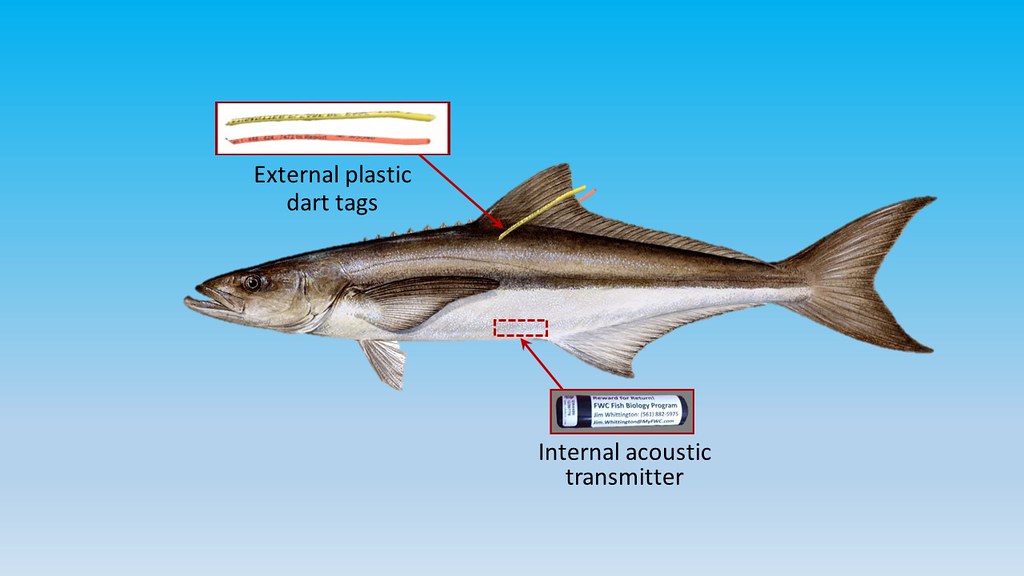

Cobia Researchers use Transmitters as well as Tags to Gather Data on Migratory Patterns

I must admit to having very limited personal experience with Cobia, having caught one sub-legal fish to-date. However, that does not diminish my fascination with the fish, particularly since I ran across a 2019 report from the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission titled “Management Profile for Gulf of Mexico Cobia.” This 182-page report is definitely not a quick read and I have thus far only scratched the surface by digging into a few chapters that caught my interest. Nevertheless, it is so full of detailed life history, biology and everything else “Cobia” that it is definitely worth a look. This posting will highlight some of the fascinating aspects of Cobia and why the species is so highly prized by so many people.

Cobia (Rachycentron canadum) are the sole species in the fish family Rachycentridae. They occur worldwide in most tropical and subtropical oceans but in Florida waters, we actually have two different groups. The Atlantic stock ranges along the Eastern U.S. from Florida to New York and the Gulf stock ranges From Florida to Texas. The Florida Keys appear to be a mixing zone of sorts where Cobia from both stocks go in the winter. As waters warm in the spring, these fish head northward up the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida. The Northern Gulf coast is especially important as a spawning ground for the Gulf stock. There may even be some sub-populations within the Gulf stock, as tagged fish from the Texas coast were rarely caught going eastward. There also appears to be a group that overwinters in the offshore waters of the Northern Gulf, not making the annual trip to the Keys. My brief summary here regarding seasonal movement is most assuredly an over-simplification and scientists agree more recapture data is needed to understand various Cobia stock movements and boundaries.

Worldwide, the practice of Cobia aquaculture has exploded since the early 2000’s, with China taking the lead on production. Most operations complete their grow-out to market size in ponds or pens in nearshore waters. Due to their incredible growth rate, Cobia are an exceptional candidate for aquaculture. In the wild, fish can reach weights of 17 pounds and lengths of 23 inches in their first year. Aquaculture-raised fish tend to be shorter but heavier, comparatively. The U.S. is currently exploring rules for offshore aquaculture practices and cobia is a prime candidate for establishing this industry domestically.

Spawning takes place in the Northern Gulf from April through September. Male Cobia will reach sexual maturity at an amazing 1-2 years and females within 2-3 years. At maturity, they are able to spawn every 4-6 days throughout the spawning season. This prolific nature supports an average annual commercial harvest in the Gulf and East Florida of around 160,000 pounds. This is dwarfed by the recreational fishery, with 500,000 to 1,000,000 pounds harvested annually from the same region.

One of the Cobia’s unique features is that they are strongly attracted to structure, even if it is mobile. They are known to shadow large rays, sharks, whales, tarpon, and even sea turtles. This habit also makes them vulnerable to being caught around human-made FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices). Most large Cobia tournaments have banned the use of FADs during their events to recapture a more sporting aspect of Cobia fishing.

To wrap this up I’ll briefly recount an exciting, non-fish-catching, Cobia experience. My son and I were in about 35 feet of water off the Wakulla County coastline fishing near an old wreck. Nothing much was happening when I noticed a short fin breaking the water briefly, about 20 yards behind a bobber we had cast out with a dead pinfish under it. I had not seen this before and was unaware of what was about to happen. When the fish ate that bait and came tight on the line the rod luckily hung up on something in the bottom of the boat. As the reel’s drag system screamed, a Cobia that I gauged to be 4-5 feet long jumped clear out of the water about 40 yards from us. Needless to say, by the time we gained control of the rod it was too late; a heartbreaking missed opportunity. Every time we have been fishing since then, I just can’t stop looking for that short, pointed fin slicing towards one of our baits.