by Ray Bodrey | Jul 11, 2022

The University of Florida/IFAS Extension faculty are reintroducing their acclaimed “Panhandle Outdoors LIVE!” series. Conservation lands and aquatic systems have vulnerabilities and face future threats to their ecological integrity. Come learn about the important role of these ecosystems.

The St. Joseph Bay and Buffer Preserve Ecosystems are home to some of the one richest concentrations of flora and fauna along the Northern Gulf Coast. This area supports an amazing diversity of fish, aquatic invertebrates, turtles, salt marshes and pine flatwoods uplands.

This one-day educational adventure is based at the St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve near the coastal town of Port. St. Joe, Florida. It includes field tours of the unique coastal uplands and shoreline as well as presentations by area Extension Agents.

Details:

Registration fee is $45.

Meals: breakfast, lunch, drinks & snacks provided (you may bring your own)

Attire: outdoor wear, water shoes, bug spray and sun screen

*if afternoon rain is in forecast, outdoor activities may be switched to the morning schedule

Space is limited! Register now! See below.

Tentative schedule:

All Times Eastern

8:00 – 8:30 am Welcome! Breakfast & Overview with Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension

8:30 – 9:35 am Diamondback Terrapin Ecology, with Rick O’Connor, Escambia County Extension

9:35 – 9:45 am Q&A

9:45- 10:20 am The Bay Scallop & Habitat, with Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension

10:20 – 10:30 am Q&A

10:30 – 10:45 am Break

10:45 – 11:20 am The Hard Structures: Artificial Reefs & Marine Debris, with Scott Jackson, Bay County Extension

11:20 – 11:30 am Q&A

11:30 – 12:05 am The Apalachicola Oyster, Then, Now and What’s Next, with Erik Lovestrand, Franklin County Extension

12:05 – 12:15 pm Q&A

12:15 – 1:00 pm Lunch

1:00 – 2:30 pm Tram Tour of the Buffer Preserve (St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve Staff)

2:30 – 2:40 pm Break

2:40 – 3:20 pm A Walk Among the Black Mangroves (All Extension Agents)

3:20 – 3:30 pm Wrap Up

To attend, you must register for the event at this site:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/panhandle-outdoors-live-at-st-joseph-bay-tickets-404236802157

For more information please contact Ray Bodrey at 850-639-3200 or rbodrey@ufl.edu

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 9, 2020

Pitt Spring in the Florida Panhandle is one of more than 1,000 freshwater springs in the state. Springs serve as ‘windows’ to groundwater quality, since the water that flows from them comes largely from the Upper Floridan Aquifer. Photo: A. Albertin

As Florida residents, we are so fortunate to have the Floridan Aquifer lying below us, one of the most productive aquifer systems in the world. The aquifer underlies an area of about 100,000 square miles that includes all of Florida and extends into parts of Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina, as well as parts of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1). The Floridan Aquifer consists of the Upper and Lower Floridan Aquifer.

Figure 1. Map of the extent of the Floridan Aquifer. Areas in gray show where the aquifer is buried deep below the land surface, while areas in light brown indicate where the aquifer is at land surface. Many springs in Florida are found in these light brown areas. Source: USGS Publication HA 730-G.

Aquifers are immense underground zones of permeable rocks, rock fractures and unconsolidated (or loose) material, like sand, silt and clay that hold water and allow water to move through them. Both fresh and saltwater fill the pores, fissures and conduits of the Floridan Aquifer. Saltwater, which is more dense than freshwater, is found in all areas of the deeper aquifer below the freshwater.

The thickness of the Floridan Aquifer varies widely. It ranges from 250 ft. thick in parts of Georgia, to about 3,000 ft. thick in South Florida. Water from the Upper Floridan Aquifer is potable in most parts of the state and is a major source of groundwater for more than 11 million residents. However, in areas such as the far western panhandle and South Florida, where the Floridan Aquifer is very deep, the water is too salty to be potable. Instead, water from aquifers that lie above the Floridan is used for water supply.

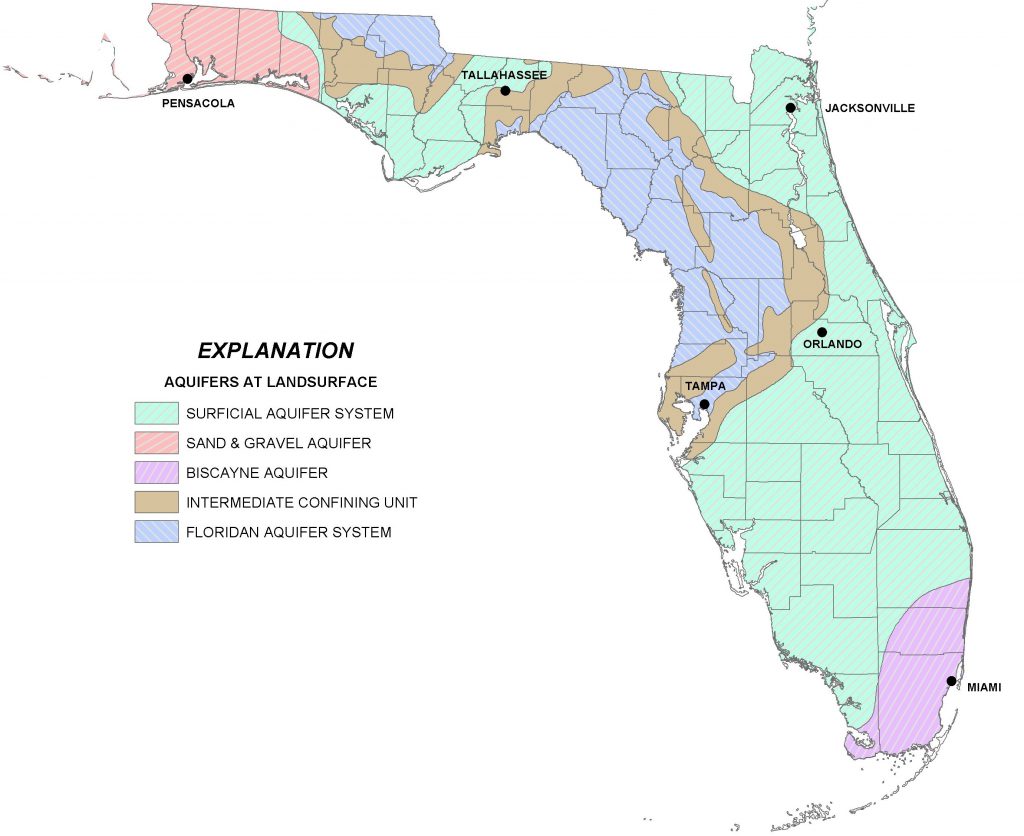

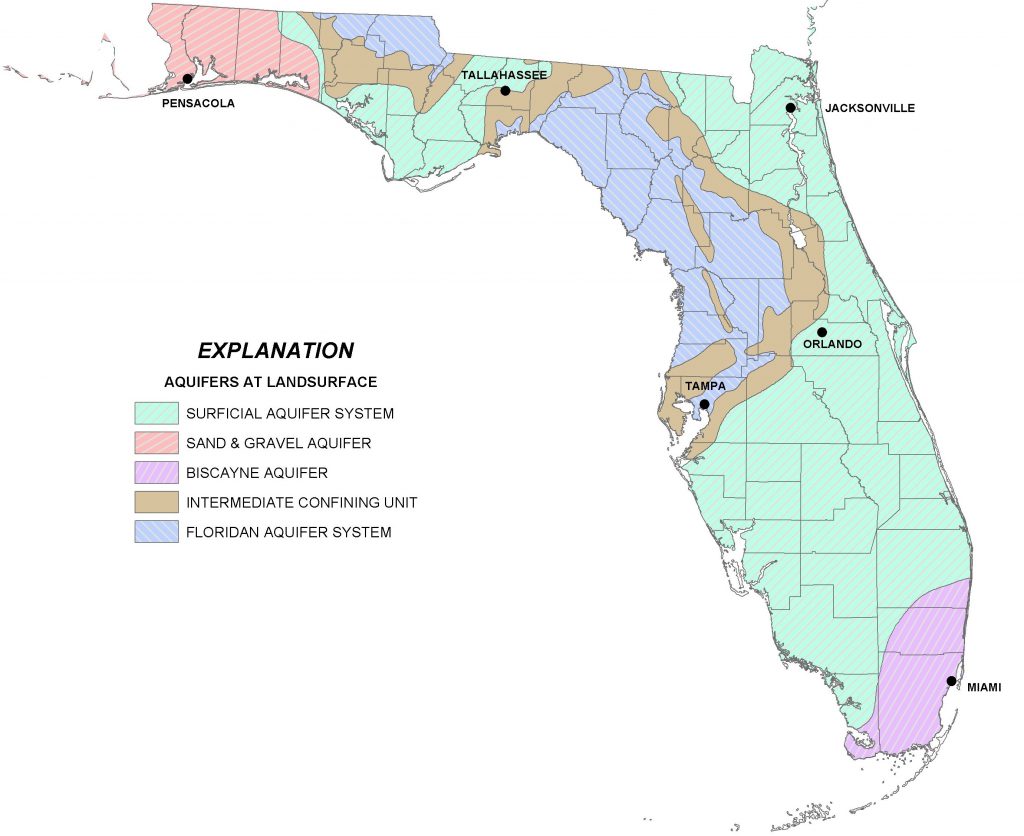

There are actually several major aquifer systems in Florida that lie on top of the Floridan Aquifer and are important sources of groundwater to local areas (Figure 2):

- The Sand and Gravel Aquifer in the far western panhandle is the main source of water for Santa Rosa and Escambia Counties. It is made up of of sand and gravel interbedded with layers of silt and clay.

- The Biscayne Aquifer supplies water to Dade and Broward Counties and southern Palm Beach County. A pipeline also transports water from this aquifer to the Florida Keys. The aquifer is made of permeable limestone and less permeable sand and sandstone.

- The Surficial Aquifer System (marked in green in the map in Figure 2) is the major source of drinking water in St. Johns, Flagler and Indian River counties, as well as Titusville and Palm Bay. It is typically shallow (less than 50 ft. thick) and is often referred to as a ‘water table’ aquifer, but in Indian River and St. Lucie Counties, it can be up to 400 ft. thick.

- Not included in Figure 2 is a fourth aquifer, the Intermediate Aquifer System in southwest Florida. It lies at a depth between the Surficial Aquifer System and the Floridan Aquifer. It is found south and east of Tampa, in Hillsborough and Polk counties and extends south through Collier County. It is the main source of water supply for Sarasota, Charlotte and Lee counties, where the underlying Floridan Aquifer is too salty to be potable.

Figure 2. A map of four major aquifer systems in the state of Florida at land surface. The Floridan Aquifer (in blue) underlies the entire state, but in areas north and east of Tampa it is found at the surface. The Surficial (green), Sand and Gravel (red), and Biscayne Aquifer (purple/pink) lie on top of the Floridan Aquifer. A confining unit (area in brown) consists of impermeable materials like thick layers of fine clay that prevent water from easily moving through it. Source: FDEP.

All of the aquifer systems in Florida are recharged by rainfall. In general, freshwater from deeper portions of the aquifer tends to have better water quality than surficial systems, since it is less susceptible to pollution from land surfaces. But, in areas where groundwater is excessively pumped or wells are drilled too deeply, saltwater intrusion occurs. This is where the underlying, denser saltwater replaces the pumped freshwater. Florida’s highly populated coastal areas are particularly susceptible to saltwater intrusion, and this is one of the main reasons that water conservation is a major priority in Florida.

More information about the Floridan Aquifer System and overlying aquifers can be found at the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (https://fldep.dep.state.fl.us/swapp/Aquifer.asp#P4) and in the UF EDIS Publication ‘Florida’s Water Reosurces’ by T. Borisova and T. Wade (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe757).

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 31, 2020

Contact you local county health department office for information on how to test your well water. Image: F. Alvarado Arce

Residents that rely on private wells for home consumption are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) recommends private well users test their water once a year for bacteria and nitrate.

Unlike private wells, public water supply systems in Florida are tested regularly to ensure that they are meeting safe drinking water standards.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Your best source of information on how to have your water tested is your local county health department. Most health departments test drinking water and they will let you know exactly what samples need to taken and ho w to submit a sample. You can also submit samples to a certified private lab near you.

Contact information for county health departments can be located at: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

Contact information for private certified laboratories are found at https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp

Why is it important to test for bacteria?

Labs commonly test for both total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically). This usually costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

- Coliform bacteria are a large, diverse group of bacteria and most species are harmless. But, a positive test for total coliforms shows that bacteria are getting into your well water. They are used as indicators – if coliform bacteria are present, other pathogens that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than to test for a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

- Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces, in food and in the environment. E. coli are one group of fecal coliform bacteria. Most strains of E. coli are harmless, but some strains can cause diarrhea, urinary tract infections, and respiratory illnesses among others.

To ensure safe drinking water, FDOH strongly recommends disinfecting your well if the water tests positive for (1) only total coliform bacteria, or (2) both total coliform and fecal coliform bacteria (or E. coli). Disinfection is usually done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your well can be found at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/_documents/well-water-facts-disinfection.pdf

Why is it important to test for nitrate concentration?

High levels of nitrate in drinking water can be dangerous to infants, and can cause “blue baby syndrome” or methemoglobinemia. This is where nitrate interferes with the blood’s capacity to carry oxygen. The Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) allowed for nitrate in drinking water is 10 milligrams nitrate per liter of water (mg/L). It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that is drinking well water or when well water is used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L nitrate, use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply) until the problem is addressed. Nitrates in well water can come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are in your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, contact your local health department for more information.

In addition to once a year, you should also have your well water tested when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well and/or septic tank were affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are not the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your what they recommend you should get the water tested for, because it can vary depending on where you live.

FDOH maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users at http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html, which includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 8, 2018

We have been posting articles discussing some of the issues our estuaries are facing; this post will focus on one of the things you can do to help reduce the problem – a Florida Friendly Yard.

Florida Friendly Landscaping saves money and reduces our impact on the estuarine environment.

Photo: UF IFAS

The University of Florida IFAS developed the Florida Friendly Landscaping Program. It was developed to be included in the Florida Yards & Neighborhoods (FYN) program, HomeOwner and FYN Builder and Developer programs, and the Florida-Friendly Best Management Practices for Protection of Water Resources by the Green Industries (GI-BMP) Program in 2008.

A Florida Friendly Yard is based on nine principals that can both reduce your impact on local water quality but also save you money. Those nine principals are:

- Right Plant, Right Place – We recommend that you use native plants in the right location whenever possible. Native plants require little fertilizer, water, or pesticides to maintain them. This not only reduces the chance of these chemicals entering our waterways but also saves you money. The first step in this process is to have your soil tested at your local extension office. Once your soil chemistry is known, extension agents can do a better job recommending native plants for you.

- Water Efficiently – Many homeowners in the Florida panhandle have irrigation systems on timers. This makes sense from a management point of view but can lead to unnecessary runoff and higher water bills. We have all seen sprinkler systems operating during rain events – watering at that time certainly is not needed. FFY recommends you water only when your plants show signs of wilting, water during the cooler times of day to reduce evaporation of your resource, and check system for leaks periodically. Again, this helps our estuaries and saves you money.

- Fertilize Appropriately – No doubt, plants need fertilizer. Water, sunlight, and carbon dioxide produce the needed energy for plants to grow, but it does not provide all of the nutrients needed to create new cells – fertilizers provide needed those nutrients. However, plants – like all creatures – can only consume so much before the remainder is waste. This is the case with fertilizers. Fertilizer that is not taken up by the plant will wash away and eventually end up in a local waterway where it can contribute to eutrophication, hypoxia, and possible fish kills. Apply fertilizers according to UF/IFAS recommendations. Never fertilize before a heavy rain.

- Mulch – In a natural setting, leaf litter remains on the forest floor. The environment and microbes, recycling needed nutrients within the system, break down these leaves. They also reduce the evaporation of needed moisture in the soil. FFY recommends a 2-3” layer of mulch in your landscape.

- Attract Wildlife – Native plants provide habitat for a variety of local wildlife. Birds, butterflies, and other creatures benefit from a Florida Friendly Yard. Choose plants with fruits and berries to attract birds and pollinators. This not only helps maintain their populations but you will find enjoyment watching them in your yard.

- Manage Yard Pests Responsibly – This is a toughie. Once you have invested in your yard, you do not want insect, or fungal, pests to consume it. There is a program called the Integrated Pest Management Program (IPM) that is recommended to help protect your lawn. The flow of the program basically begins with the least toxic form of pest management and moves down the line. Hopefully, there will not be a need for strong toxic chemicals. Your local county extension office can assist you with implementing an IPM program.

- Recycle – Return valuable nutrients to the soil and reduce waste that can enter our waterways by composting your turfgrass clippings, raked leaves, and pruned plants.

- Reduce Stormwater Runoff – ‘All drains lead to the sea’ – this line from Finding Nemo is, for the most part, true. Any water leaving your property will most likely end in a local waterway, and eventually the estuary. Rain barrels can be connected to rain gutters to collect rainwater. This water can be used for irrigating your landscape. I know of one family who used it to wash their clothes. Rain barrels must be maintained properly to not produce swarms of mosquitos, and your local extension office can provide you tips on how to do this. More costly and labor intensive, but can actually enhance your yard, are rain gardens. Modifying your landscape so that the rainwater flows into low areas where water tolerant plants grow not only reduces runoff but also provides a chance to grow beautiful plants and enhance some local wildlife.

- Protect the Waterfront – For those who live on a waterway, a living shoreline is a great way to reduce your impact on poor water quality. Living shorelines reduce erosion, remove pollutants, and enhance fisheries – all good. A living shoreline is basically restoring your shoreline to a natural vegetative state. You can design this so that you still have water access but at the same time help reduce storm water runoff issues. Planting below the mean high tide line will require a permit from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, since the state owns that land, and it could require a breakwater just offshore to help protect those plants while they are becoming established. If you have questions about what type of living shoreline you need, and how to navigate the permit process, contact your local county extension office.

Santa Rosa Sound

Photo: Dr. Matt Deitch

These nine principals of a Florida Friendly Yard, if used, will go a long way in reducing our communities’ impact on the water and soil quality in our local waterways. Read more at http://fyn.ifas.ufl.edu/about.htm.

by Laura Tiu | Nov 20, 2017

The lodge at Camp Helen State Park was the perfect backdrop for the Coastal Dune Lake Seminar Series Water School. Brandy Foley of the Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance shares her paleolimnology research work on the lakes.

On a beautiful October day, 35 people gathered at the Camp Helen State Park lodge to share information about the rare Coastal Dune Lakes (CDLs) that line the coast of Walton and Bay Counties. Organized by the University of Florida Extension Programs in Bay and Walton counties, the Water School included a morning seminar series featuring speakers from various groups that work together to support the lakes. Laura Tiu, Sea Grant Agent for Walton and Okaloosa counties started off the day giving a broad overview of the history and ecology of the lakes. Brandy Foley of the Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance shared her research on the paleolimnology, or study of the lake sediments over time, of two coastal dune lakes. Clayton Iron Wolf, a ranger at Camp Helen, gave a summary of the importance of Lake Powell and its benefit to the park. Jeff Talbert of the Atlanta Botanical Garden thrilled attendees with his pictures and research on the Deer Lake State Park restoration project. Norm Capra, who wears many hats, including that of the Lake Powell Community Alliance and Friends of Camp Helen State Park, shared the work they have done promoting conservation of shorebirds there. Dr. Dana Stephens, Director of the Mattie Kelly Environmental Institute at Northwest Florida State College shared analyses of many years of water chemistry and quality data collected on the lakes. Melinda Gates, Environmental Specialist for Walton County, wrapped up with a presentation on the efforts to protect and preserve the lakes.

The attendees seemed pleased with the event with one hundred percent of attendees rating the quality of information presented, usefulness of information, speakers’ knowledge, overall value of the program, and quality of location as good or excellent. The seminar helped attendees identify important roles of the CDLs in the ecosystem and understand why it is important to protect them. Several participants plan to make behavior changes based in the workshop including: joining or volunteering with Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance, Audubon, Sierra Club or Lake Watch Volunteers; sharing the information; living minimally; and engaging in activism. The seminar was followed by a kayak tour lead by Scott Jackson, Bay County Sea Grant Agent, to the outflow of Lake Powell and a visit to a faux sea turtle nest demonstration by Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. This Water School was part of a regional series offered by UF/IFAS Extension. For more information on future schools, please subscribe to our Panhandle Outdoors Newsletter.

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 29, 2017

One third of homes in Florida rely on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater, which includes wastewater from bathrooms, kitchen sinks and laundry machines. When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low.

A conventional residential septic tank and drain field under construction.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

A general rule of thumb is that with proper care, systems need to be pumped every 3-5 years at a cost of about $300 to $400. Time between pumping does vary though, depending on the size of your household, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce. If systems aren’t maintained they can fail, and repairs or replacing a tank can cost anywhere between $3000 to $10,000. It definitely pays off to maintain your septic system!

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, which is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the ground) and a drain field, or leach field. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. The liquid wastewater, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out through pipes into the drainfield, where it percolates down through the ground.

Although bacteria continually work on breaking down the organic matter in your septic tank, sludge and scum will build up, which is why a system needs to be cleaned out periodically. If not, solids will flow into the drainfield clogging the pipes and sewage can back up into your house. Overloading the system with water also reduces its ability to work properly by not leaving enough time for material to separate out in the tank, and by flooding the system. Sewage can flow to the surface of your lawn and/or back up into your house.

Failed septic systems not only result in soggy lawns and horrible smells, but they contaminate groundwater, private and public supply wells, creeks, rivers and many of our estuaries and coastal areas with excess nutrients, like nitrogen, and harmful pathogens, like E. coli.

It is important to note that even when traditional septic systems are maintained, they are still a source of nitrogen to groundwater; nitrate is not fully removed from the wastewater effluent.

How can you properly care for your septic system?

Here are a some basic tips to keep your system working properly so that you can reduce maintenance costs by avoiding system failure, and so that you can reduce your household’s impact on water pollution in your area.

- Don’t flush trash down the toilet. Only flush regular toilet paper. Toilet paper treated with lotion forms a layer of scum. Wet wipes are not flushable, although many brands are labelled as such. They wreak havoc on septic systems! Avoid flushing cigarette butts, paper towels and facial tissues, which can take longer to break down than toilet paper.

- Think at the sink. Avoid pouring oil and fat down the kitchen drain. Avoid excessive use of harsh cleaning products and detergents, which can affect the microbes in your septic tank (regular weekly or so cleaning is fine). Prescription drugs and antibiotics should never be flushed down the toilet.

- Limit your use of the garbage disposal. Disposals add organic matter to your septic system, which results in the need for more frequent pumping. Composting is a great way to dispose of your fruit and vegetable scraps instead.

- Take care at the surface of yourtank and drainfield. To work well, a septic system should be surrounded by non-compacted soil. Don’t drive vehicles or heavy equipment over the system. Avoid planting trees or shrubs with deep roots that could disrupt the system or plug pipes. It is a good idea to grow grass over the drainfield to stabilize soil and absorb liquid and nutrients.

- Conserve water. You can reduce the amount of water pumped into your septic tank by reducing the amount you and your family use. Water conservation practices include repairing leaky faucets, toilets and pipes, installing low cost, low-flow showerheads and faucet aerators, and only running the washing machine and dishwasher when full. In the US, most of the household water used is to flush toilets (about 27%). Placing filled water bottles in the toilet tank is an inexpensive way to reduce the amount of water used per flush.

- Have your septic system pumped by a certified professional. The general rule of thumb is every 3-5 years, but it will depend on household size, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce.

By following these guidelines, you can contribute to the health of your family, community and environment, as well as avoid costly repairs and septic system replacements.

You can find excellent information on septic systems a the US EPA website: https://www.epa.gov/septic. The Florida Department of Health website provides permiting information for Florida and a list of certified maintenance entities by county: http://www.floridahealth.gov/Environmental-Health/onsite-sewage/index.html.

The Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) identified septic systems as the major source of nitrate in Wakulla Springs, located in Wakulla County. Excess nitrate is thought to promote algal growth, leading to the degradation of the biological community in the spring.

Photo: Andrea Albertin