by Scott Jackson | May 26, 2022

Nutrients found in food waste are too valuable to just toss away. Small scale composting and vermicomposting provide opportunity to recycle food waste even in limited spaces. UF/IFAS Photo by Camila Guillen.

During the summer season, my house is filled with family and friends visiting on vacation or just hanging out on the weekends. The kitchen is a popular place while waiting on the next outdoor adventure. I enjoy working together to cook meals, bbq, or just make a few snacks. Despite the increased numbers of visitors during this time, some food is leftover and ultimately tossed away as waste. Food waste occurs every day in our homes, restaurants, and grocery stores and not just this time of year.

The United States Food and Drug Administration estimates that 30 to 40 percent of our food supply is wasted each year. The United States Department of Agriculture cites food waste as the largest type of solid waste at our landfills. This is a complex problem representing many issues that require our attention to be corrected. Moving food to those in need is the largest challenge being addressed by multiple agencies, companies, and local community action groups. Learn more about the Food Waste Alliance at https://foodwastealliance.org

According to the program website, the Food Waste Alliance has three major goals to help address food waste:

Goal #1 REDUCE THE AMOUNT OF FOOD WASTE GENERATED. An estimated 25-40% of food grown, processed, and transported in the U.S. will never be consumed.

Goal #2 DONATE MORE SAFE, NUTRITIOUS FOOD TO PEOPLE IN NEED. Some generated food waste is safe to eat and can be donated to food banks and anti-hunger organizations, providing nutrition to those in need.

Goal #3 RECYCLE UNAVOIDABLE FOOD WASTE, DIVERTING IT FROM LANDFILLS. For food waste, a landfill is the end of the line; but when composted, it can be recycled into soil or energy.

All these priorities are equally important and necessary to completely address our country’s food waste issues. However, goal three is where I would like to give some tips and insight. Composting food waste holds the promise of supplying recycled nutrients that can be used to grow new crops of food or for enhancing growth of ornamental plants. Composting occurs at different scales ranging from a few pounds to tons. All types of composting whether big or small are meaningful in addressing food waste issues and providing value to homeowners and farmers. A specialized type of composting known as vermicomposting uses red wiggler worms to accelerate the breakdown of vegetable and fruit waste into valuable soil amendments and liquid fertilizer. These products can be safely used in home gardens and landscapes, and on house plants.

Composting meat or animal waste is not recommended for home composting operations as it can potentially introduce sources of food borne illness into the fertilizer and the plants where it is used. Vegetable and Fruit wastes are perfect for composting and do not have these problems.

Composting worms help turn food waste into valuable fertilizer. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones

Detailed articles on how vermicomposting works are provided by Tia Silvasy, UF/IFAS Extension Orange County at https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/orangeco/2020/12/10/vermicomposting-using-worms-for-composting and https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/sfylifasufledu/orange/hort-res/docs/pdf/021-Vermicomposting—Cheap-and-Easy-Worm-Bin.pdf Supplies are readily available and relatively inexpensive. Please see the above links for details.

A small vermicomposting system would include:

• Red Wiggler worms (local vendors or internet)

• Two Plastic Storage Bins (approximately 30” L x 20” W x 17” H) with pieces of brick or stone

• Shredded Paper (newspaper or other suitable material)

• Vegetable and Fruit Scraps

Red Wiggler worms specialize in breaking down food scraps unlike earthworms which process organic matter in soil. Getting the correct worms for vermicomposting is an important step. Red Wigglers can consume as much as their weight in one day! Beginning with a small scale of 1 to 2 pounds of worms is a great way to start. Sources and suppliers can be readily located on the internet.

Worm “homes” can be constructed from two plastic storage bins with air holes drilled on the top. Additional holes put in the bottom of the inner bin to drain liquid nutrients. Pieces of stone or brick can be used to raise the inner bin slightly. Picture provided by UF/IFAS Extension Leon County, Molly Jameson

Once the worms and shredded paper media have been introduced into the bins, you are ready to process kitchen scraps and other plant-based leftovers. Food waste can be placed in the worm bins by moving along the bin in sections. Simply rotate the area where the next group of scraps are placed. See example diagram. For additional information or questions please contact our office at 850-784-6105.

Placing food scraps in a sequential order allows worms to find their new food easily. Contributed diagram by L. Scott Jackson

Portions of this article originally published in the Panama City News Herald

UF/IFAS is An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Rick O'Connor | May 14, 2020

As we embrace the marine life of the Gulf of Mexico during this year of “Embracing the Gulf”, we are currently hooked on worms. In the last article we talked about the gross and creepy flatworms. Gross because they are flat, pale in color, only have a mouth so they have to go to the bathroom using it – and creepy in that many of them are parasites, living in the bodies over vertebrates (particularly fish) and that is just creepy. You may ask why would we even “embrace” such a thing? Well… because they do exist and most of us know nothing about them.

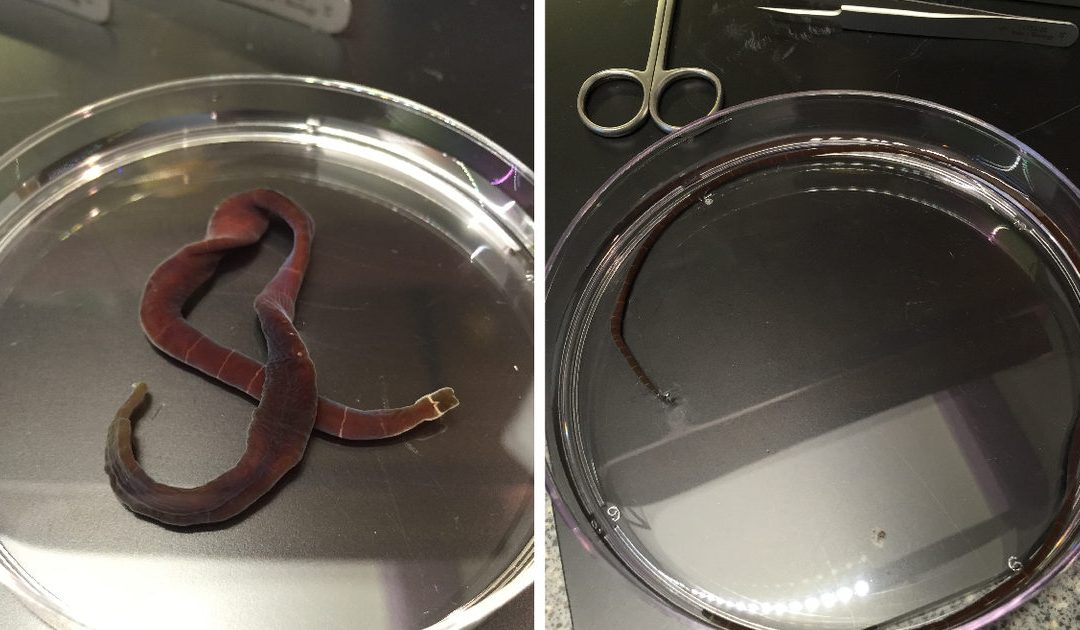

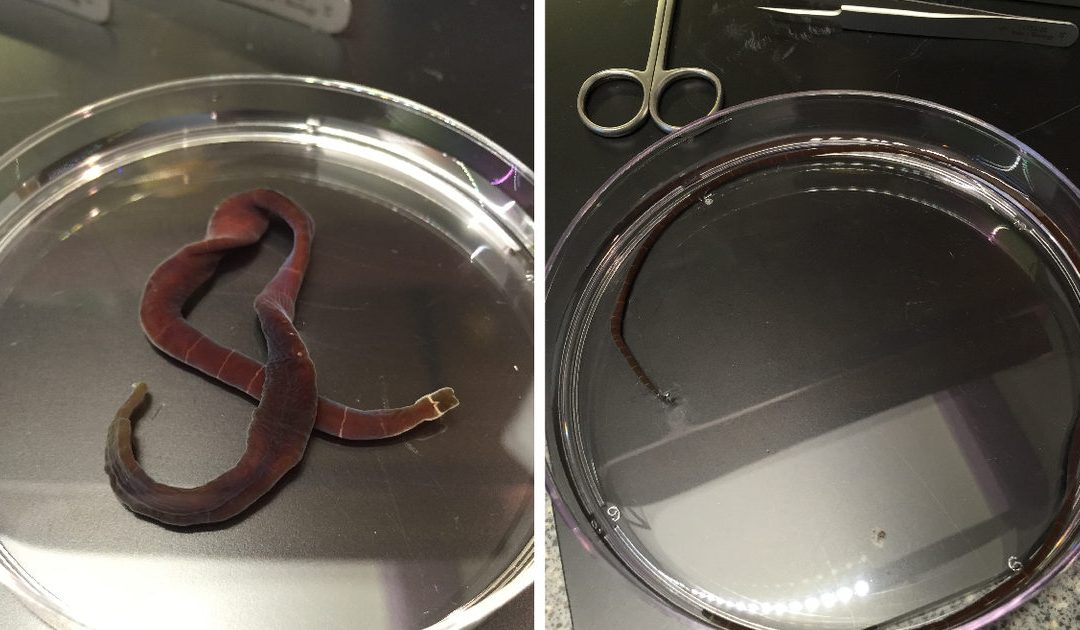

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

This week we continue with worms. We continue with a different kind of flatworm. They are not as gross, but maybe a little creepy. They are called nemertean worms and I am pretty sure (a) you have never heard of them, and (b) you have never seen one. So why “embrace” these? Well… again it is education. They do exist, and one day you MAY see one – and know what you are looking at.

Nemerteans are flatworms. They are usually pale in color but a different from the classis fluke or tapeworm in a couple of ways.

1) They do have a way for food to enter and another for waste to leave, what we call a complete digestive tract – and that’s nice.

2) They have this long extension connected to their head called a proboscis. Many of them have a dart at the end they can use to kill their prey – and that’s creepy.

3) And as mentioned, most are carnivores, feeding on small invertebrates – and that’s okay.

We rarely see them because they are nocturnal – hiding under rocks, shells, seaweed during the day and hunting at night. Most are about eight inches long but some in the Pacific reach almost eight feet!

I would put that in the creepy file.

As we said, they are usually pale in color, though some may have yellow, orange, red, or even green hues to them. Their heads are spade shaped and, again, hold a retracted proboscis. This proboscis can be over half the length of the worm. At the end is a stylet (a dart) which they can use to stab their prey (small invertebrates). They can stab repeatedly, like using a knife, – they may stab and grab, like using a claw – or they may be a species that has toxin and kills their prey that way.

Nice.

Some would add this to the creepy file as well. A long pale worm, moving at night, extending a long proboscis when they get near you with a sharp dart at the end they essentially “sting” you like a bee.

Yea, creepy.

But we NEVER hear about such things with humans. They hunt small invertebrates like amphipods, isopods, and things like that. If you picked one up, would it stick the dart in you? My hunch would be yes – I honestly don’t know, I have only seen one to two in the 35+ years I have been teaching marine science and I did not pick them up. I have never met anyone who has and have never read “DON’T PICK THESE UP – VERY DANGERSOUS”. So, my hunch is that it would not be very painful at all.

But don’t take my word for it – again, I have rarely seen one… so, don’t pick them up 😊

There are about 650 species of nemertean worms in the world, 22 live in the Gulf of Mexico, and 16 live in the northern Gulf (near us). They are basically marine, move across the environment on their slime trails, seeking prey primarily by the sense of smell at night. Unlike the flukes and tapeworms, there are male and females in this group. They fertilize their eggs externally to make the next generation of these harpooning hunters of the Gulf.

I don’t know if you will ever come across one of these. You will know it by the flat body, pale color, and spade-shaped head, but I think it would be pretty neat to find one. There are more worms to learn about in the Gulf of Mexico, but we will do that in another edition.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 12, 2015

In the final segment of this 3 part series on worms we will discuss the largest, most commonly encountered members of the worm world… the Annelids.

Neredia are one of the more common polychaete worms.

Photo: University of California Berkley

Annelids differ from the other two groups of worms we have discussed in that they have segmented bodies. They are largest of the worms and the most anatomically complexed. The fluids of their coelomic cavity serve as a skeleton which supports muscle movement and increases locomotion. The annelids include marine forms called Polychaetes, the earthworms, and the leeches.

POLYCHAETES

Polychaetes are the most diverse group of annelids and most live in the marine environment. They differ from earthworms and leeches in that they have appendages called parapodia and do not possess a clitellum. In size they range from 1 mm (0.04”) to 3 m (10’) but most are around 10 cm (4”). Many species display beautiful coloration and some possess toxic spines.

There are 3 basic life forms of polychaetes; free-swimming, sedentary, and boring. The free-swimming polychaetes are found swimming in the water column, crawling across the seabed, or burrowing beneath the sediments. Some species are responsible for the “volcanoes” people see when exploring the bottom of our local bays. Most sedentary polychaetes produce tubes within which they live. Some tubes are made of elastic organic material and others are hard, stony, and calcareous. “Tubeworms” rarely leave their tubes but extend appendages from the tube to collect their food. Most feed on organic material either in the water column or on the seabed but some species collect and consume small invertebrates. There are commensal polychaetes but parasitism is rare. All polychaetes have gills and a closed circulatory system and some have a small heart. As with the other Annelids, polychaetes do have a small brain and are aware of light, touch, and smell; most species dislike light. Reproduction involves males and females who release their gametes in the water where fertilization occurs and drifting larva form.

The tube of a common tubeworm found on panhandle beaches; Diopatra.

Photo: University of Michigan

EARTHWORMS

Aside from parasitic tapeworms and leeches, earthworms are one of the more commonly recognized varieties of worms. Many folks actually raise earthworms for their gardens or for fish bait; a process known as vermiculture. Earthworms differ from polychaetes in that they do not have parapodia but DO possess a clitellum, which is used in reproduction. Though most live in the upper layers of the soil there are freshwater species within this group. They are found in all soils, except those in deserts, and can number over 700 individuals / m2. The number of earthworms within the soil is dependent on several factures including the amount of organic matter, the amount of moisture, soil texture, and soil pH. Scientists are not sure why earthworms surface during heavy rains but it has been suggested that the heavy drops hitting the ground can generate vibrations similar to those of an approaching mole; a reason many think “fiddling” for worms works. Earthworms can significantly improve soil conditions by consuming soil and adding organics via their waste, or castings. Unlike polychaetes, earthworms lack gills and take in oxygen through their skin, one reason why they most live in moist soils. Another difference between them and polychaetes is in reproduction. Aquatic polychaetes can release their gametes into the water where they are fertilized but terrestrial earthworms cannot do this. Instead two worms will entangle and exchange gametes; there are no male and females in this group. The fertilized eggs are encased in a mucous cocoon secreted by the clitellum.

LEECHES

Here is another creepy worm… leeches. Leeches are segmented, and thus annelids, and like earthworms they lack the parapodia found in polychaetes and possess a clitellum for reproduction. Most leeches are quite small, 5 cm (2”) but there is one from the Amazon that reaches 30 cm (12”). Most are very colorful and mimic items within the water, such as leaves. They differ from earthworms in that they are flatter and actually lack a complete coelomic cavity; which most annelids do have. They also possess “suckers” at the head and tail ends.

The ectoparasite we all call the leech.

Photo: University of Michigan

Leeches prefer calm, shallow water but are not fans low pH tannic rivers. If conditions are favorable their numbers can be quite high, as many as 10,000 / m2. They are found worldwide but are more common in the northern temperate zones of the planet; North America and Europe.

Some species feed by using an extending proboscis which they insert and remove body fluids, but most actually have jaws with teeth and use them to rip flesh to cause bleeding, cutting as frequently as 2 slices/second. Those with teeth possess an anesthesia that numbs the area where the bite occurs. Both those with and without teeth possess hirudin, which is an anticoagulant, allowing free-bleeding until the worm is full. Those who feed on blood tend to prey on vertebrates and most species are specific to a particular type of vertebrate. It is known they can detect the smell of a human and will actually swim towards one who is standing still in the water. It takes several hundred days for a leech to digest a full meal of blood and so they feed only once or twice a year. They remove most of the water from the blood once they swallow and require the assistance of bacteria in their guts to breakdown the proteins. They can detect day and night, and prefer to hide from the light. However when it is feeding time they are actually attracted to daylight to increase their chance of finding a host. Vibrations, scent, even water temperature (signaling the presence of warm blooded animals) can stimulate a leech to move towards a potential prey. Leeches, like earthworms, reproduce using a clitellum and develop a cocoon.

Though most find worms a disgusting group of creatures to be avoided, they are actually very successful animals and many species are beneficial to our environment. We hope you learned something from this series and will try and learn more.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 28, 2015

The round body of a microscopic nematode.

Photo: University of Nebraska at Lincoln

In the first article of this series we discussed the how unpleasant the subject of worms were but how beneficial many species are to our environment. We highlighted the flatworms and this week we will look at the roundworms.

There are a variety of round-shaped worms but the term “roundworm” is usually associated with the Phylum Nematoda; and more commonly called “nematodes”. There are over 10,000 species of nematodes on our planet and they are found in all habitats from the polar region to the tropics and even in deserts. They are found in freshwater and marine systems and are quite common in soils. Within an acre of land there could be literally billions of them.

As the name suggests their bodies are round, not flat, and smooth, not segmented; which separates them from the other two groups we are writing about. Most are very small (< 2.5mm – 0.10”) but some may reach 5cm (2”). Most are carnivorous, some even consume fleas in your yard, but others graze on algae, and others detritus. Many species have a stylet (needle) they use to puncture the cell wall of their prey to consume the internal organic matter. They do not have a developed brain but they do have a series of nerves that run throughout their body. Most are connected to exterior structures associated with the sense of touch, such as setae. There are generally male and female worms in this group and the males are typically smaller in size. However hermaphroditism does exist.

As with most groups of worms, it is the parasites that we really dislike – and there are plenty of parasitic nematodes. They infest a lot of different species. Some live on the outside of plants while others live on the inside. Some are parasitic only at the adult stage, some only as a juvenile, others begin within invertebrates and move to plants as adults. They typically exit one organism through the feces and infest another when the feces is consumed by another.

The life cycle of the human hookworm.

Center for Disease Control

Many species of nematodes have a primary and secondary host life cycle, similar to the flatworms, but others complete the entire life cycle within one organism. Hookworms, a common nematode found in humans, enters the body and feeds on blood cells. The young larva live in the environment and can for a few days in good conditions. When they contact a human they penetrate the skin and move through the circulatory system to the lung. Here they burrow into the bronchioles (airway) and work themselves to the pharynx where they are swallowed by the host and eventually end in the intestine. Within the intestine they feed on blood cells within the intestinal wall. When they reproduce the eggs are released within the feces and enter the environment. If conditions within the environment are good the eggs will hatch and the cycle begins again. Pinworms and whipworms are also parasitic nematodes that infest humans.

Though we dwell on the negative aspect of the parasitic nematodes many species are used indicators of soil health and can give farmers a better idea of the condition of their soil. Suggesting to them what to plant or what they need to do to condition their soil to plant a specific crop.

Next week we will look at the most familiar of the worms – the segmented ones.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 21, 2015

I am afraid worms are not the most pleasant topic to write about but few people know much about them. I was once told when I was a student that if you wanted to become known as a scientist study worms, no one else is.

When we hear the term “worm” negative things enter our minds: parasites, disease, uncleanliness to name a few, but many worms are actually beneficial by removing detritus (decaying organic matter) from the environment; the garbage cleaners in a sense. There are at least 10 phyla of worms but this series will focus on the three major groups; flatworms, roundworms, and segmented worms.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematod flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

Flatworms include three classes and two of those are parasitic; those are the flukes and tapeworms. Most are very small and emerge in low or no light. The parasitic forms typically live in the gut but can infest other organs of their host organism. There are several species that infest humans but most are specific to a particular group of animals. The flatness of their bodies may have to do with moving materials in and out of the body. Most flatworms lack well develop organ systems so gas exchange occurs through the skin. The more the flat they are, the more surface area they have, the more gas exchange can occur. This is supported by the fact that the larger the flatworm is the more flat they are.

Tubellarians are basically non-parasitic flatworms and are mostly aquatic, many living in the marine environment. Some crawl across the seabed but others can actually swim. As with other flatworms, their digestive tract is incomplete (meaning there is only one opening – the mouth – where food comes in and waste goes out), and this mouth is located half way down their body on the ventral side. Most of these flatworms are carnivorous feeding on small invertebrates and dead organisms. They do have “eyespots” which do not form images but can detect light. Most flatworms are what we call “negatively phototaxic” meaning they sense light but do not like it and will burrow or hide when the sun rises.

Trematoda are what we call flukes and are parasitic. Most are only a few centimeters long but some can reach a meter (3ft.) or more! Flukes have a protective covering on their skin to protect them from the enzymes of their host’s internal environment. Their life cycle requires a second host, meaning that the adult lives in one type of animal but the larval stage occurs in another. Adult flukes live in vertebrates (typically fish), and the secondary hosts are usually invertebrates (typically snails). The eggs (cyst) produced by the adults leave the host organism through their feces. Once in the environment the secondary host consumes them where the larva develop. Eventually the secondary host is consumed by the primary host (fish) where the larva develop into an adult and the cycle begins again. They typically infest the gut but can infest other organs as well.

A tapeworm actually has a round head which posses hooks to attach to the lining of the gut.

Photo: University of Nebraska Omaha

Cestods are one of the more recognized flatworms; these are the tapeworms. Tapeworms lack a digestive tract and most absorb all of their nutrients on through their flat bodies. Like their fluke cousins, tapeworms are endoparasites but almost all of them infest the digestive tract. Like their fluke cousins they require a secondary host, usually an arthropod (insect, spider, or crustacean). With a vertebrate serving as the host organism.

Though there are flukes and tapeworms that infest humans most are found in fish and are specific to that group. The ones that do infest humans require the secondary host cycle described above and, because of sanitary conditions we live in, are not commonly found in the population. This cannot be said for parts of the world where sanitary conditions are not to our standards. As horrible as parasites sound many species of nonparasitic flatworms are beneficial by removing detritus from lakes, rivers, and bays.

Next week… Roundworms.