Excessive hurricane rainfall in some areas, to moderate drought conditions along the Gulf Coast this fall impacted hay production and quality in the Southeast in 2017. Photo credit: Doug Mayo

Weather had a dramatic impact on range, pasture, and hay production in the Southern Region in 2017. The dramatic extremes of excessive rainfall received in Texas and Florida from hurricanes, to abnormally dry and moderate drought conditions across the Southern U.S. this fall have led to lower levels of hay production and quality in many southern states. Weather conditions have also negatively affected cool-season forages in many parts of the Southeast. The focus of this article is to prepare producers for the 2018 grazing and hay seasons.

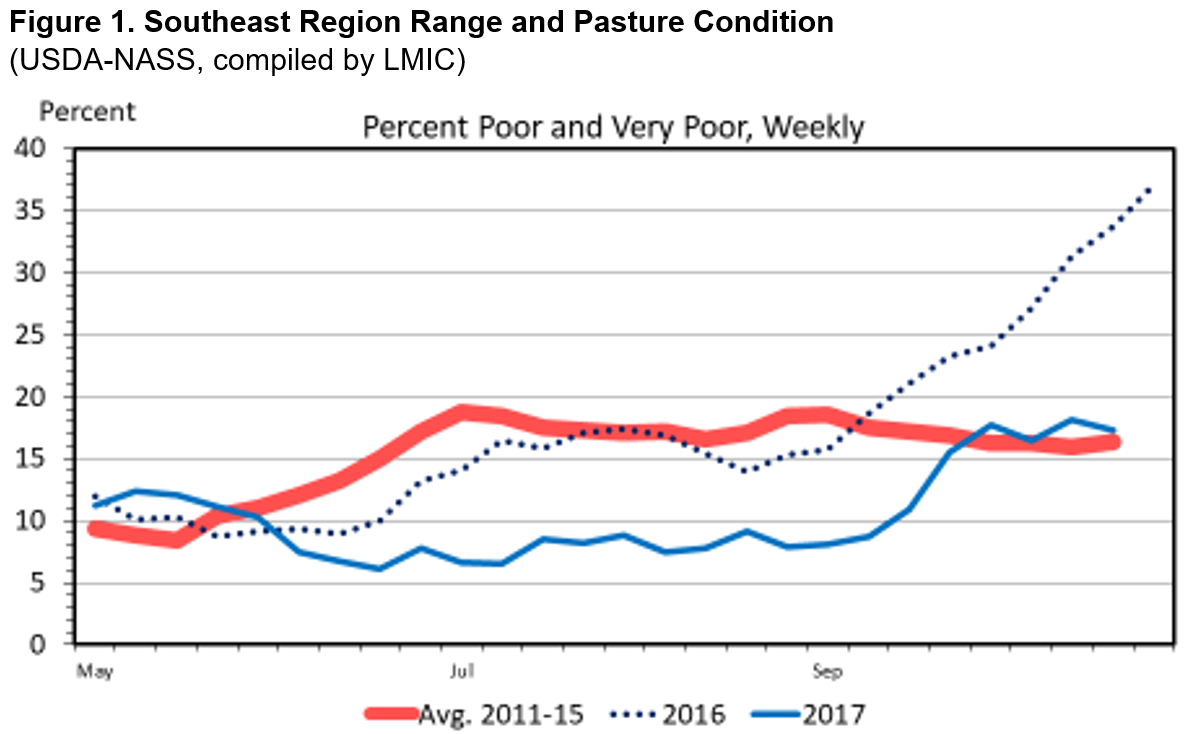

Southeast Region Range and Pasture Conditions

Range and pasture conditions during 2017 for the Southeast Region have traced at or better than the typical seasonal pattern, where pasture conditions usually decline from spring to fall as heat and dryness persist. Additionally, 2017 range and pasture conditions continued to decline October through December, as they are usually the driest months of the year for most southeastern states.

As indicated in Figure 1 below, range and pastures rated in “poor and very poor” condition by mid-year in 2016 were at 17% increasing to 37% by mid-October. In 2017, mid-year range and pasture conditions were 7% “poor and very poor,” increasing to 17% by mid-October. The year-over year improvement in range and pasture conditions rated “poor and very poor” in the Southeast region was 19%. While range and pasture conditions declined during September and October, cattle producers in the Southeast were in a much-improved situation compared to a year ago.

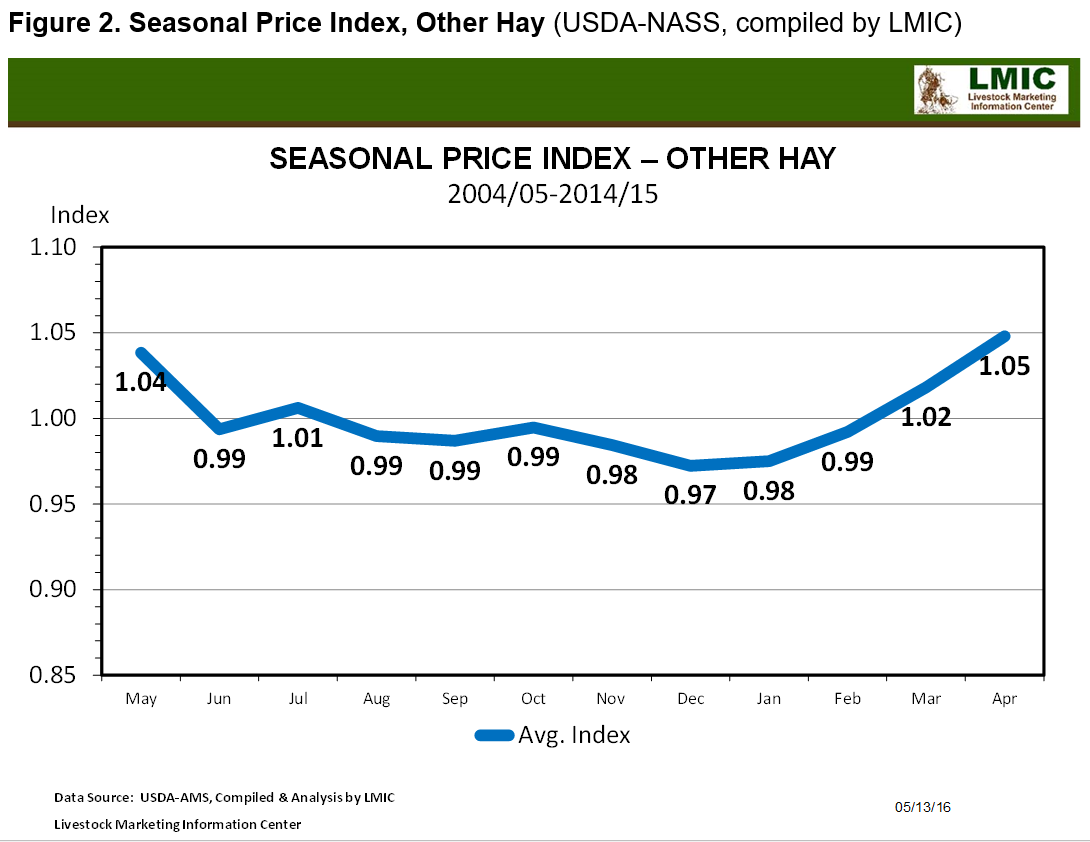

U.S. Other Hay

USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) estimated that U.S. Other hay prices ranged from $113 to $127/ton during 2017. U.S. Other Hay should be interpreted as all hay that does not fall into the categories of Alfalfa or Alfalfa mixed hay. This hay is best represented as cow hay. A combination of lower hay supply available, and an increase in beef cattle inventory has hay prices tracking above year-ago levels. Total hay supplies for the 2017-2018 crop year (May 2017-April 2018) are estimated to be down approximately 2% from the prior year.

Alternatively, that matches up with an expanding cattle herd that increased by 2% in 2016. The additional demand from roughage consuming animals that requires being fed through the winter and the lower supply of other hay has many analysts expecting slightly higher prices as Winter 2017-2018 continues. However, barring any significant weather events in 2018, demand usually doesn’t outpace supply to the point where prices rise dramatically.

The five-year average on Other Hay is estimated at $131/ton. Figure 2 examines the seasonal price index of other hay from a ten-year period, 2004-2005 to 2014-2015 marketing year. The seasonal price index of Other Hay ranges from 0.97 to 1.05. The seasonal low of 0.97 occurs during December and seasonal high of 1.05 during April. Based on the seasonal price index, producers who need additional hay supplies for Winter 2017-2018 should begin acquiring hay supplies now as other hay prices increase from 0.97 to 1.05 from December to April.

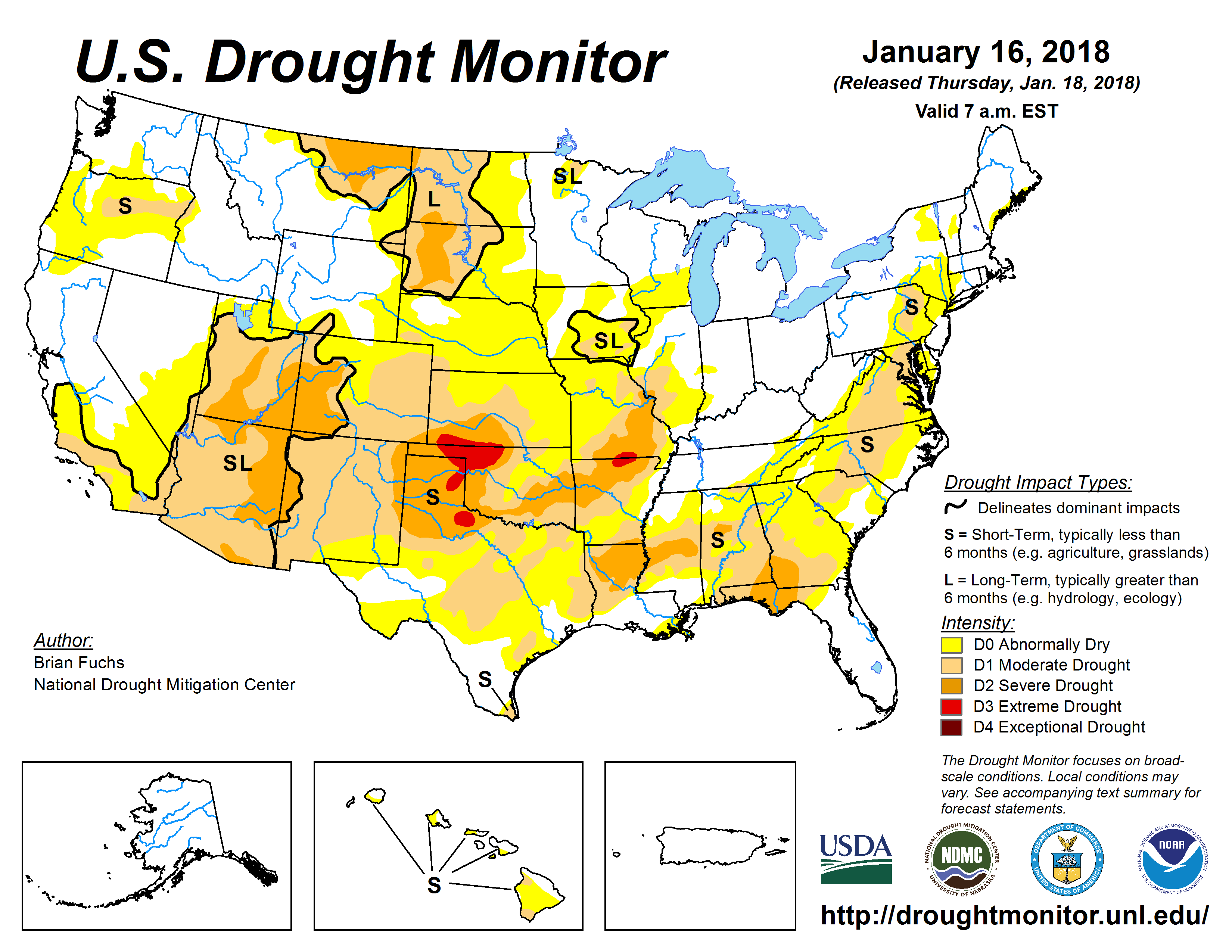

U.S. Drought

The U.S. Drought Monitor map provides a summary of drought conditions across the United States to help communicate precipitation deficits that are occurring. As seen in Figure 3 below, the map denotes four levels of drought intensity ranging from moderate drought (D1) to exceptional drought (D4) and one level of “abnormal dryness” (D0). The January 16, 2018 U.S. Drought Monitor saw continued intensification and expansion of areas of drought across portions of the Southeast and Southern Plains. Most of the Southeast United States was under abnormally dry to moderate drought conditions with some areas intensifying into severe drought conditions. The areas highlighted in yellow are abnormally dry. Areas under a light brown, orange, red, and dark brown in the map above are under moderate, severe, or extreme drought, respectively.

The January 16, 2018 U.S. Drought Monitor saw continued intensification and expansion of areas of drought across portions of the Southeast and Southern Plains. Most of the Southeast United States was under abnormally dry to moderate drought conditions with some areas intensifying into severe drought conditions. The areas highlighted in yellow are abnormally dry. Areas under a light brown, orange, red, and dark brown in the map above are under moderate, severe, or extreme drought, respectively.

U.S. Drought Monitor Highlights:

- Most of Texas has some level of drought conditions. This comes just four months following the landfall of Hurricane Harvey that dumped more than 60 inches of rain along the Texas coast.

- According to the latest drought monitor, an “extreme” and “severe” drought is expanding from Arkansas into Kansas, Missouri, Texas and Louisiana.

- A larger swath of the country from central Texas through the Carolinas continues to experience drought conditions that are adversely impacting winter forage production in these areas.

- Only a few states within the continental United States are drought free, which includes Kentucky, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ohio.

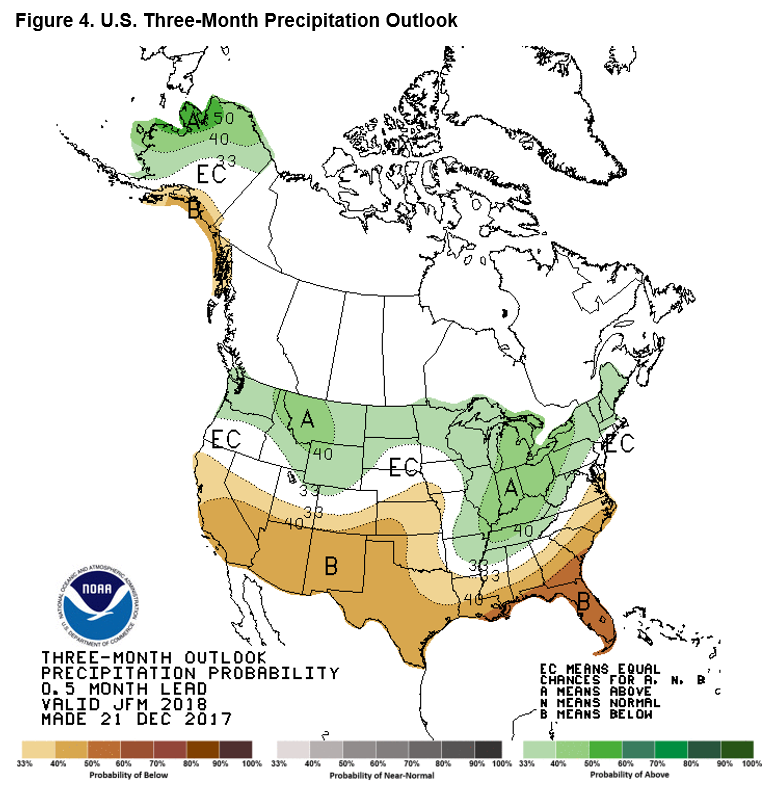

U.S. Winter Weather Outlook

Forecasters at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center recently released the U.S. Winter Outlook. Their outlook confirmed a La Niña weather cycle emerging for a second year in a row. This provides additional guidance of how this year’s winter weather is expected to play out. For cattle producers in the southern region, a typical La Niña weather pattern implies warmer than average temperatures and a drier than normal winter, sometimes leading to drought conditions and wildfires in the Southeast. Before discussing the weather outlook below, I do want to remind readers that the forecasts made by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center are probabilities (% chance) for below, near, or above-average climate outcomes with the maps showing only the most likely outcome. Because the probabilities shown are less than 100%, it means there is no guarantee you will see precipitation departures from normal that match the color on the map. While even though one outcome is more likely than another, there is always a chance that a lower probability outcome could occur.

In Figure 4, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration Climate Prediction Center issues probabilistic seasonal precipitation forecasts to help communities understand the risks and opportunities when making climate-sensitive decisions. Places where the forecast odds favor a much drier than usual winter (brown colors) or much wetter than usual winter (blue-green), or where the probability of a dry winter, a wet winter, or a near-normal winter are all equal (white and labeled EC for “equal chances”). This doesn’t mean that near-average precipitation is expected this winter in those regions, but rather that there’s no tilt in the odds toward any of the three outcomes. Additionally, the darker the color, the stronger the chance of that outcome. Lastly, please keep in mind that the maps show the most likely outcome where there is greater confidence, but this is not the only possible outcome. As seen in Figure 4, NOAA Climate Prediction Center’s U.S. Winter Outlook expects precipitation from December through February to be above normal across most of the northern United States and drier-than-normal conditions are most likely across the entire southern U.S. Probabilities below-normal precipitation are exceeding 50% along the eastern Gulf Coast to the coasts of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. Additionally, their Winter Outlook also predicts warmer-than-normal conditions are most likely across the southern U.S and along the East Coast. The rest of the country falls into the equal chance category, which means they have an equal chance for above-, near- or below-normal temperatures and/or precipitation because there is not a strong enough climate signal in these areas to shift the odds.

As seen in Figure 4, NOAA Climate Prediction Center’s U.S. Winter Outlook expects precipitation from December through February to be above normal across most of the northern United States and drier-than-normal conditions are most likely across the entire southern U.S. Probabilities below-normal precipitation are exceeding 50% along the eastern Gulf Coast to the coasts of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. Additionally, their Winter Outlook also predicts warmer-than-normal conditions are most likely across the southern U.S and along the East Coast. The rest of the country falls into the equal chance category, which means they have an equal chance for above-, near- or below-normal temperatures and/or precipitation because there is not a strong enough climate signal in these areas to shift the odds.

Summary

The Winter of 2017-18 isn’t shaping up to be very kind to producers. It isn’t expected to be as difficult as a year ago, when many cattle producers in the Deep South experienced severe drought requiring the selling off of cattle due to hay and feedstuff shortages. However, with below normal rainfall expected throughout the Southeast for the next few months from the La Niña weather pattern, drought is expected to persist into the upcoming spring. Many producers are currently dealing with establishment and growth issues of winter pastures from the lack of moisture. La Niña is expected to continue to impact production from cool-season annual forages. Alternatively, for areas of the southeast that received an adequate supply of rainfall on winter pastures, this may provide improved growing conditions from warmer than normal temperatures during the winter. Hopefully, U.S. cattle producers already have forage and feed supplies secured for this winter. If not, producers should begin acquiring the additional feedstuffs needed, as prices are expected to increase as we move forward and the available supply declines. Lastly, the unfavorable weather experienced this fall and winter may begin discouraging some in the livestock industry from their herd expansion plans for 2018.

- Grazing Stocker Cattle on Warm-Season Annual Forages - August 19, 2022

- Che Trejo wins 2022 UF Top Rancher Challenge at FCA Convention - June 17, 2022

- Marketing Feeder Cattle at 6-Year Highs in 2022 - February 25, 2022