Cool-season forages have the potential to produce low-cost feed with a high concentration of nutrients resulting in a high average daily gains and in an increase of profits, if the pasture is managed well. North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC), Marianna – FL. Photo by Jose Dubeux, UF/IFAS.

Cleber Lopes de Sousa and Marcelo Wallau, UF/IFAS Agronomy Department Forage Team

Most pasture acres in Florida are warm-season, perennial grasses; as winter comes, their production and nutritive value decrease. An alternative to overcome this shortfall of forage without feeding hay all winter, is to plant cool-season forages. Cool-season forages have the potential to produce low-cost biomass with a high concentration of nutrients, resulting in a high average daily gain and an increase in profitability, if these annual pastures are managed well. That said, understanding what constitutes good management is essential.

Management starts at establishment

Undoubtedly, the most important step towards abundant winter grazing is good pasture establishment. There are several factors that can help ensure successful establishment: 1) use of certified seeds from superior varieties, 2) seed bed preparation (tillage and/or herbicide), 3) planting techniques that place seed at the appropriate depth and ensure good seed-soil contact, 4) sufficient fertilization (based on a soil test), and 5) moisture availability which can be ensured if irrigation is available in the fall.

When to start grazing?

When to start of grazing is an important decision, and should be based on the pasture status rather than the need for forage. Grazing too early, while plants are not fully established, will reduce plant productivity and persistence. Small plants will not have fully developed root systems, and as you remove leaves, you also remove the plant’s capacity to grow more forage. More total forage will ultimately be produced if grazing is delayed until the pasture has a chance to fully establish. As a rule of thumb, do not start grazing small grains (rye, oat and triticale) before they reach around 12 inches, or 8 inches for ryegrass.

The major factors determining when an annual pasture will be ready to graze are 1) planting date, 2) weather conditions, 3) variety chosen and 4) soil fertility. Planting date and weather are related. If no irrigation is available, you should only plant if conditions are favorable. In relation to varieties, small grains tend to grow faster than ryegrass, and within each species there is considerable variation in time to maturity based on cultivar. A starter fertilizer with 30 lb/A of nitrogen (N) is very important, but will not take those high-yielding cool-season grasses too far. A follow up fertilization with 50-80 lb N/A around 45 – 60 days after planting (depending on moisture) will make the pasture jump and will shorten the time to wait to start of grazing.

Livestock capacity on the pasture

A good cool-season pasture will hold around 2 stockers or replacement heifers per acre, but that is very general. It is better to be on the lower side of the stocking rate than to be short on forage. See Estimating Herbage Mass on Pastures to Adjust Stocking Rate for guidance on how to more precisely calculate stocking rate. The key principle is only harvest about half of what is available. Why is that? Why not harvest more and take more advantage of the pasture? First, because regrowth of the pasture is dependent on the amount of leaves left behind after grazing (the stubble); the shorter the stubble, the slower the regrowth rate and the longer it will take before the pasture is ready to graze again. Second, allowing animals graze to a short stubble height requires wasted energy and forces them to eat lower-quality material. Third, and this is especially true for small ruminants, the closer to the ground you make animals graze, the greater the exposure to parasites. The amount of internal parasite eggs tends to be higher closer to the soil level (closer to the feces).

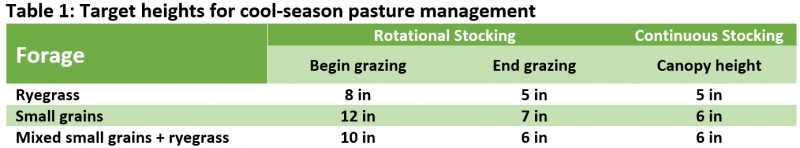

The forage regrowth rate is dependent on the residual amount of forage, which means, the stubble height has a direct impact on forage production. Practically speaking, if the cattle consume forage at a higher rate than it can be produced by the pasture, the yield and stand longevity will decline, and the utilization period will finish prematurely. Hence, a minimum of 1500 lb of dry matter (DM) per acre is necessary to initiate grazing of the pasture, and an ideal 1000 – 1200 lb DM/A stubble should be left behind, so your pasture can keep up with grazing. The easiest way to do this management is by continuously measuring stubble height. The quick guide below (Table 1) may help. Maintaining adequate stubble height in a pasture also prevents erosion and compaction of the soil, improve nutrients cycling and water retention, and reduces incidence of weeds. This is especially important for those areas which will be planted in row crops later in the spring.

–

Leave more stubble for faster regrowth

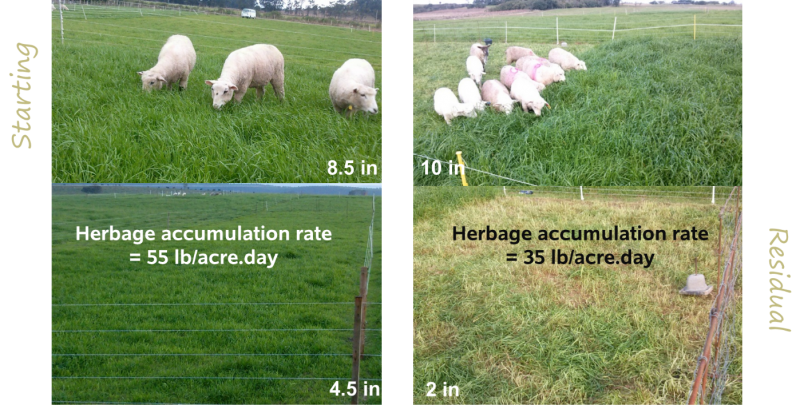

In a rotational stocking system, by leaving an adequate stubble, you can come back to the same paddock more frequently. The grazing removes part of taller vegetative tillers in the canopy, breaking apical dominance (main stem) and stimulating generation of new tillers, which results in a denser pasture. The frequency of this process regulates tiller life, so a long resting interval can result in early maturity of the plants, causing a sharp reduction of nutritive value. This means that leaving more behind and moving the animals more frequently can result in greater forage production and better utilization. The important thing to understand is that livestock eat leaves, and plants need those leaves to produce more forage; there must be a balance between what you remove and what is left behind for the plants to keep producing.

Figure 1. Less intense and more frequent grazing (left) vs. more intense and less frequently grazing (right) on ryegrass. Almost 60% greater forage productivity (daily herbage accumulation rate, in lbs. of dry matter per acre) and over double average daily gain (Pictures: Jean Savian; Savian et al., 2018)

–

Figure 2. A situation where grazing was delayed (rye is flowering) followed by a heavy grazing. The productivity of the pasture is affected on both ends, by reduced growth at maturity and minimal regrowth after grazing. In this case, it is unlikely you can get more than one grazing event out of the pasture. Credit: Marcelo Wallau, UF/IFAS

–

Ensure a good nutritional balance

In the initial stage of cool-season forage pasture, the quantity of fiber in the plants is low, around 40% compared to regular values of 60%, which means digestibility and protein levels are high. Simultaneously, the animals have often been feed hay with low nutritive value and high levels of fiber. The rumen microbiome has been adapted to a high fiber diet and the abrupt change will result in a shock for the microbiome. This can lead to diarrhea which means, losses of animal weight and wasted resources. In order to avoid the abrupt change, an acclimatization period is advised. This acclimatization can be accomplished by feeding hay before turning the animals into cool-season pastures, followed by a gradual increase in access to the pasture.

Stay tuned for our UF/IFAS Extension cool-season forage field days around the state. We have 34 sites around Central, North and Panhandle Florida showcasing several varieties and mixtures of cool-season forages that may imporve forage production on your operation. Contact your local extension office for more information.

–

References:

Savian, J.V., R.M.T. Schons, D.E. Marchi, T.S. de Freitas, G.F. da Silva Neto, et al. 2018. Rotatinuous stocking: A grazing management innovation that has high potential to mitigate methane emissions by sheep. J. Clean. Prod. 186: 602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.162.

- Does Planting Perennial Peanut in Bahiagrass Pastures Pay Off? - March 8, 2024

- Results from the 2023 UF/IFAS Silage Corn, Sorghum, and Millet Variety Trials - January 19, 2024

- Managing the Effects of Excessive Heat in Silage Corn and Other Crops - September 15, 2023