The Jackson County Master Gardeners are hosting a hosting a Mushroom Growing Workshop on Saturday, November 18 at the Jackson County Extension Office, 2741 Penn Ave., Marianna, FL.

Healthy and Delicious, Oyster Mushrooms Can be Grown at Home

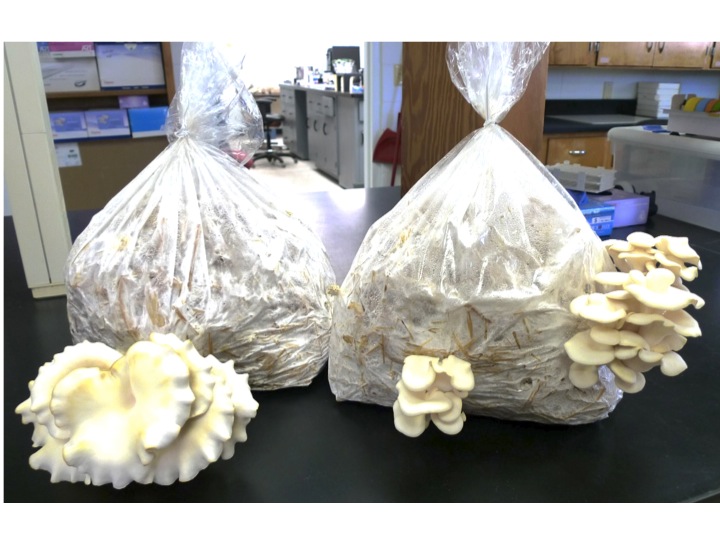

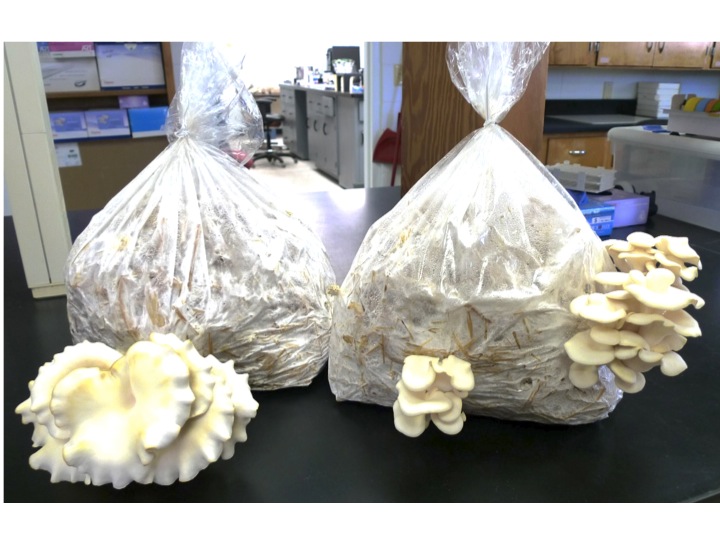

Following basic instructions, grow oyster mushrooms using sterilized straw, a plastic bag, oyster mushroom spawn, and water. Photo by Sunny Liao.

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) – which have nothing to do with oysters besides their similar shape – are some of the most delicate, subtlety flavored, and easiest to prepare mushrooms of the culinary world.

They can easily be fried, stir-fried, or braised within a matter of minutes in broths, vinegar, wines, and sauces; or added to soups, stuffed, or mixed with chopped garlic. Other mushrooms, such as shiitake, are sturdier and impart a meatier flavor and texture to a dish. Oyster mushrooms, especially those lighter in color, pair well with seafood or a white meat. Highly perishable, you will want to freeze oyster mushrooms after sautéing with butter or oil to preserve, or dehydrate them to enjoy at a later date.

In addition to being an easy mushroom to prepare, oyster mushrooms are a great source of fiber, protein, and many vitamins and minerals, as well as an excellent source of the antioxidant ergothioneine.

Oyster mushrooms can come in many shades, from cream-colored, to gray, golden, tan, and brown. Their white colored gills, when present, extend from beneath the cap down to their very short stems. They are often described as smelling slightly like licorice and can grow up to about nine inches, but are best consumed young when tender and mild.

Oyster mushrooms grow in many subtropical and temperate environments, commonly found in nature growing in layers, decomposing the wood of dying hardwood trees. This decomposition benefits the ecosystem, as the mushrooms return nutrients and minerals back into the soil.

Interestingly, oyster mushrooms are one of the few known carnivorous mushrooms. The mycelia of the fungi can consume and digest nematodes, which is how it is thought the oyster mushrooms acquire nitrogen.

Arguably one of the best qualities of oyster mushrooms are the ease to which they can be cultivated at home. Using sterilized straw, a plastic bag, oyster mushroom spawn, water, and following basic instructions, oyster mushroom can be produced in as little as two weeks!

You can learn all about oyster mushroom production on the Penn State Extension page: Cultivation of Oyster Mushrooms (http://extension.psu.edu/plants/vegetable-fruit/mushrooms/publications/guides/cultivation-of-oyster-mushrooms).

Once you have the materials gathered, follow this guide, developed by UF/IFAS Suwannee County Extension, to prepare oyster mushrooms bags at home: Preparation of Oyster Mushroom Bags (http://suwannee.ifas.ufl.edu/documents/PREPARATIONOFOYSTERMUSHROOMBAGS.2012.pdf).

As well as being healthy and delicious, oyster mushroom cultivation is fun, and just needs a small amount of space and effort!

Get Those Fairies Off My Lawn!

Mushrooms often are grouped in a circle in your lawn. This is due to the circular release of spores from a central mushroom. “Fairy Ring” is a term used to describe this phenomenon. Fairy rings can be caused by multiple mushroom species such as Chlorophyllum spp., Marasmius spp., Lepiota spp., Lycoperdon spp., and other basidiomycete fungi.

Occurrence

Fairy rings most commonly invade your yard during the summer months, when the Florida panhandle receives the most rain. The mushrooms cause the development and spread of the rings by the release of spores. Spores produce more mushrooms and are similar to the seed produced by plants.

Fairy Ring “Types”

Fairy rings can be seen in three forms:

- Type I rings have a zone of dead grass just inside a zone of dark green grass. Weeds often invade the dead zone.

- Type II rings have only a band of dark green turf, with or without mushrooms present in the band.

- Type III rings do not exhibit a dead zone or a dark green zone, but a ring of mushrooms is present.

The size and fill of rings varies considerably. Rings are often 6 ft or more in diameter. The fill of a ring can range from a quarter circle to a semicircle or full circle.

Cultural Controls

The rings will disappear naturally, but it could take up to five years. Although it is possible to dig up the fairy ring sites, it is a good possibility the rings will return if the food source (buried, rotting wood or other organic matter) for the fungi is still present underground.

In some situations, the fungi coat the soil particles and make the soil hydrophobic (meaning it repels water), which will result in rings of dead grass. If the soil under this dead grass is dry but the soil under healthy grass next to it is wet, then it is necessary to aerate or break up the soil under the dead grass with a pitchfork or other cultivation tool.

Chemical Controls

Effective fungicides include products containing the active ingredients azoxystrobin, flutolanil, metconazole, pyraclostrobin, and triticonazole.

Fungicides inhibit the fungus only. They do not eliminate the dark green or dead rings of turfgrass and do not solve the dry soil problem.

A homeowner’s guide to lawn fungicides can be found at the University of Florida/IFAS Extension Electronic Data Information Source (EDIS) website (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/document_pp154).

Grow Shiitake Mushrooms in Your Backyard

Growing up, I was never too fond of mushrooms. To me, their only purpose was to ruin a perfectly good pizza. As I got older, I started to warm up slightly toward raw button mushrooms in salads – with enough dressing, that is. But it wasn’t until I experienced my first taste of fresh shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes) – introduced to me sautéed in butter – that I truly began to understand their intrigue. Their rich, almost smoky flavor, could transform any dish into something spectacular.

It was with the shiitakes, locally grown on a small Panhandle farm, that I finally developed my love for mushrooms. They could be added to so many dishes – simmered alongside chopped garlic, or in broth, a reduction of wine, or cream. Toss shiitakes with pasta, add in lieu of meat in a creamy risotto, or use them to enrich a soup or quiche.

I learned that shiitake mushrooms are not only delicious, but they are packed with nutrition, including fiber, protein, multiple vitamins, calcium, as well as an excellent source of antioxidants. But what I really found fascinating is how shiitake mushrooms are cultivated.

When the shiitakes are ready to fruit, arrange the logs so that the mushrooms can easily be harvested. Photo by Stephen Hight, USDA

To understand their production, you must first understand that mushrooms are merely the fruiting body, or sexual organs, of the fungi. Mycelia, which is the vegetative portion of the fungi, colonize logs and only form spore containing mushrooms when they are ready to reproduce. The Florida Panhandle is an excellent location to grow shiitake mushrooms, as they strongly prefer to grow on oak tree logs, such as laurel oaks, which is a hardwood species native to our area.

The logs must be fresh to avoid colonization by unwanted fungi, so producers must first cut down oak trees during fall or winter, when the trees have large amounts of stored carbohydrates. It is important to do this sustainably, ideally as part of a forest thinning. The trees should be about three to eight inches in diameter and should be cut to about four-foot lengths.

The next step is to inoculate the logs with shiitake spawn. You can purchase shiitake spawn as either plugs or sawdust form. It is important to get a strain that does well in our climate, so make sure to do some research, such as learning about strains through the North American Mycological Association.

To inoculate, drill holes into the logs and insert the spawn with a plunger, a hammer, or a turkey baster, depending on the form of spawn. The holes should then be coated with hot wax to protect the spawn from drying out and from becoming contaminated. The logs then incubate under shade with proper moisture and aeration for about six to 18 months, giving the mycelia time to colonize the log, which includes digesting decomposing organic material to absorb nutrients.

The mycelia will fruit for about a week, and will then need a rest period of eight to 12 weeks before fruiting again. Logs fruit for about four years, but are typically more productive in the second and third year during the spring or fall. Harvest the mushrooms daily by cutting them at the base, and place in a box and refrigerate until use. By immersing the logs in cold water or chilling in cold storage, you can encourage the logs to fruit, but this process may make your logs less productive over time. When the bark begins to slough off, production will slow down and eventually stop.

For more information on growing shiitake mushrooms, visit the UF/IFAS Small Farms Mushroom Production website.