by Sheila Dunning | Jan 28, 2021

Groundhog

Groundhog Day is celebrated every year on February 2, and in 2021, it falls on Tuesday. It’s a day when townsfolk in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, gather in Gobbler’s Knob to watch as an unsuspecting furry marmot is plucked from his burrow to predict the weather for the rest of the winter. If Phil does see his shadow (meaning the Sun is shining), winter will not end early, and we’ll have another 6 weeks left of it. If Phil doesn’t see his shadow (cloudy) we’ll have an early spring. Since Punxsutawney Phil first began prognosticating the weather back in 1887, he has predicted an early end to winter

only 18 times. However, his accuracy rate is only 39%. In the south, we call also defer to General Beauregard Lee in Atlanta, Georgia or Pardon Me Pete in Tampa, Florida.

But, what is a groundhog? Are gophers and groundhogs the same animal? Despite their similar appearances and burrowing habits, groundhogs and gophers don’t have a whole lot in common—they don’t even belong to the same family. For example, gophers belong to the family Geomyidae, a group that includes pocket gophers, kangaroo rats, and pocket mice. Groundhogs, meanwhile, are members of the Sciuridae (meaning shadow-tail) family and belong to the genus Marmota. Marmots are diurnal ground squirrels. There are 15 species of marmot, and groundhogs are one of them.

Science aside, there are plenty of other visible differences between the two animals. Gophers, for example, have hairless tails, protruding yellow or brownish teeth, and fur-lined cheek pockets for storing food—all traits that make them different from groundhogs. The feet of gophers are often pink, while groundhogs have brown or black feet. And while the tiny gopher tends to weigh around two or so pounds, groundhogs can grow to around 13 pounds.

While both types of rodent eat mostly vegetation, gophers prefer roots and tubers while groundhogs like vegetation and fruits. This means that the former animals rarely emerge from their burrows, while the latter are more commonly seen out and about. In the spring, gophers make what is called eskers, or winding mounds of soil. The southeastern pocket gopher, Geomys pinetis, is also known as the sandy-mounder in Florida.

Southeastern Pocket Gopher

The southeastern pocket gopher is tan to gray-brown in color. The feet and naked tail are light colored. The southeastern pocket gopher requires deep, well-drained sandy soils. It is most abundant in longleaf pine/turkey oak sandhill habitats, but it is also found in coastal strand, sand pine scrub, and upland hammock habitats.

Gophers dig extensive tunnel systems and are rarely seen on the surface. The average tunnel length is 145 feet (44 m) and at least one tunnel was followed for 525 feet (159 m). The soil gophers remove while digging their tunnels is pushed to the surface to form the characteristic rows of sand mounds. Mound building seems to be more intense during the cooler months, especially spring and fall, and slower in the summer. In the spring, pocket gophers push up 1-3 mounds per day. Based on mound construction, gophers seem to be more active at night and around dusk and dawn, but they may be active at any time of day.

Pocket Gopher Mounds

Many amphibians and reptiles use pocket gopher mounds as homes, including Florida’s unique mole skinks. The pocket gopher tunnels themselves serve as habitat for many unique invertebrates found nowhere else.

So, groundhogs for guesses on the arrival of spring. But, when the pocket gophers are making lots of mounds, spring is truly here. Happy Groundhog’s Day.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 3, 2020

Along the northern Gulf coast is a string of long-thin sand bar islands we call barrier islands. They are called this because they serve as a barrier to the mainland from open water storms. These long sandy islands are very dynamic and constantly shift and move with the tides, currents, and waves. They can shift as far as 300 feet after a strong hurricane.

The white quartz sand beaches of the barrier island in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Life on these islands can be very tough. In addition to the constantly moving sand, there is salt spray in the wind, intense sunlight much of the year, high winds at times, and little rainfall to provide freshwater. Even though our area can receive as much as 60 inches of rain a year, much of this falls in the northern end of the counties, and not on the beaches. That said, there are freshwater ponds on some the islands and even larger dune lakes in Walton County – there life is not as hard.

As you cross a barrier island from the Gulf to the bay, you will cross distinct environmental zones. These zones are defined by the abiotic factors wind and salt spray and are named by their dominant plant forms having distinct animal life associated with them.

The beach zone seems life-less but it is not. Look beneath the sand.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The beach is barren. This is the section of sand that extends from the water line of the Gulf to the first line of dunes. Few, if any plants can grow here. The high wave energy will not allow plants to grow along the shoreline, nor in the water itself. The wind and salt spray are high and the sand ever changing. All of the animal life here lives beneath the sand. They emerge when the wind and waves have slowed and scavenge on what they can find for food. Their primary production comes from the decomposition of the strands of seagrass and seaweed that line the shore – what we call wrack. Many will filter phytoplankton from the water as the waves wash in and seabirds are constant predators. When conditions get a little too much, they migrate a little offshore in deeper water to wait it out. But here fish and larger invertebrates become predators – so, they may not stay long.

The primary dune is dominated by salt tolerant grasses like this sea oat.

Inland of the beach is the first dune line – the primary dune. This dune field is dominated by grasses because woody plants cannot tolerate the high wind. Most of these herbaceous plants have fibrous root systems that trap blowing sand and form dunes. The dominant grasses found here would include panic grass, beach elder, and the sea oat. The seeds of these plants provide food for creatures like the beach mice and some birds. Ghost crab burrows are often found here seeking shelter from the high energy environment of the beach. And, as you would expect, predators visit. Snakes, coyotes, and fox seeking the small mice.

Small round shrubs and brown grasses within the swales are characteristic of the secondary dune field.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This primary dune line blocks some of the wind and salt spray from the Gulf and allows small woody shrubs to grow. These shrubs will form a secondary dune system, which may grow slightly higher than the primary dunes. Shrubs like seaside rosemary, goldenrod, and false rosemary can be found here and give the dunes color when they are in bloom. The grasses found in the primary dune can also be found here. Beach mice and ghost crabs can work their way to this environment but because the wind is blocked by the primary dune other animals can be found here including: armadillos, opossum, a variety of snakes, and maybe even a gopher tortoise. Within the secondary dune field there are low areas that, at times, fill with rainwater. These are called swales and have their own unique wildlife. Grasses like broomsedge, needlerush, and bull rush can be found here. Along the edge you may find carnivorous plants such as the sundew. Freshwater attracts all wildlife, but the tenants could include a variety of amphibians, reptiles, and even some hardy species of fish.

The top of a pine tree within a tertiary dune.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

On the back side of the island are some of the largest dunes. These are held in place by salt tolerant trees such as live oak, pine, and even magnolia. However, these trees look different than the ones that grow in our yards. They are the same species, but their growth seems stunted and often they look like the wind has blown their growth northward. This is known as wind sculpting and all of it is caused by the salt spray coming from the Gulf. These trees form a maritime forest where a variety of wildlife species do well. Deer, armadillo, opossum, skunks, coyote, fox, raccoon, hawks, owls, eagles, all sorts of snakes and woodland birds can be found here. In these xeric conditions, it is not uncommon to find a lot of cactus. Most of these creatures are hiding during the day, but at sunset they begin to move.

During these colder winter months, we encourage you to explore these beach habitats.

by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 18, 2020

A blackgum/tupelo tree begins changing colors in early fall. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

It’s autumn and images of red, brown, and yellow leaves falling on the forest floor near orange pumpkins enter our minds. However, Florida isn’t necessarily known for its vibrant fall foliage, but if you know where to look this time of year, you can find some amazing scenery. In late fall, the river swamps can yield beautiful fall leaf color. The shades are unique to species, too, so if you like learning to identify trees this is one of the best times of the year for it. Many of our riparian (river floodplain) areas are dominated by a handful of tree species that thrive in the moist soil of wetlands. Along freshwater creeks and rivers, these tend to be bald cypress, blackgum/tupelo, and red maple. Sweet bay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana) is also common, but its leaves stay green, with a silver-gray underside visible in the wind.

The classic “swamp tree” shape of a cypress tree is due to its buttressed trunk, an adaptation to living in wet soils. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) is one of the rare conifers that loses its leaves. In the fall, cypress tress will turn a bright rust color, dropping all their needles and leaving a skeletal, upright trunk. Blackgum/tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) trees have nondescript, almost oval shaped leaves that will turn yellow, orange, red, and even deep purple, then slowly drop to the swamp floor. Blackgums and cypress trees share a characteristic adaptation to living in and near the water—wide, buttressed trunks. This classic “swamp” shape is a way for the trees to stabilize in the mucky, wet soil and moving water. Cypresses have the additional root support of “knees,” structures that grow from the roots and above the water to pull in oxygen and provide even more support.

A red maple leaf displaying its incredible fall colors. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

The queen of native Florida fall foliage, however, is the red maple (Acer rubrum) . Recognizable by its palm-shaped leaves and bright red stem in the growing season, its fall color is remarkable. A blazing bright red, sometimes fading to pink, orange, or streaked yellow, these trees can jump out of the landscape from miles away. A common tree throughout the Appalachian mount range, it thrives in the wetter soils of Florida swamps.

To see these colors, there are numerous beautiful hiking, paddling, and camping locations nearby, particularly throughout Blackwater State Forest and the recreation areas of Eglin Air Force Base. But even if you’re not a hiker, the next time you drive across a bridge spanning a local creek or river, look downstream. I guarantee you’ll be able to see these three tree species in all their fall glory.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 18, 2020

The native Florida landscape definitely isn’t known for its fall foliage. But as you might have noticed, there is one species that reliably turns shades of red, orange, yellow and sometimes purple, it also unfortunately happens to be one of the most significant pest plant species in North America, the highly invasive Chinese Tallow or Popcorn Tree (Triadica sebifera).

Chinese Tallow fall foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Native to temperate areas of China and introduced into the United States by Benjamin Franklin (yes, the Founding Father!) in 1776 for its seed oil potential and outstanding ornamental attributes, Chinese Tallow is indeed a pretty tree, possessing a tame smallish stature, attractive bark, excellent fall color and interesting white “popcorn” seeds. In addition, Chinese Tallow’s climate preferences make it right at home in the Panhandle and throughout the Southeast. It requires no fertilizer, is both drought and inundation tolerant, is both sun and shade tolerant, has no serious pests, produce seed preferred by wildlife (birds mostly) and is easy to propagate from seed (a mature

Chinese Tallow tree can produce up to 100,000 seeds annually!). While these characteristics indeed make it an awesome landscape plant and explain it being passed around by early American colonists, they are also the very reasons that make the species is one of the most dangerous invasives – it can take over any site, anywhere.

While Chinese Tallow can become established almost anywhere, it prefers wet, swampy areas and waste sites. In both settings, the species’ special adaptations allow it a competitive advantage over native species and enable it to eventually choke the native species out altogether.

In low-lying wetlands, Chinese Tallow’s ability to thrive in both extreme wet and droughty conditions enable it to grow more quickly than the native species that tend to flourish in either one period or the other. In river swamps, cypress domes and other hardwood dominated areas, Chinese Tallow’s unique ability to easily grow in the densely shaded understory allows it to reach into the canopy and establish a foothold where other native hardwoods cannot. It is not uncommon anymore to venture into mature swamps and cypress domes and see hundreds or thousands of Chinese Tallow seedlings taking over the forest understory and encroaching on larger native tree species. Finally, in waste areas, i.e. areas that have been recently harvested of trees, where a building used to be, or even an abandoned field, Chinese Tallow, with its quick germinating, precocious nature, rapidly takes over and then spreads into adjacent woodlots and natural areas.

Chinese tallow seedlings colonizing a “waste” area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Hopefully, we’ve established that Chinese Tallow is a species that you don’t want on your property and has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. The question now is, how does one control Chinese Tallow?

- Prevention is obviously the first option. NEVER purposely plant Chinese Tallow and do not distribute the seed, even as decorations, as they are sometimes used.

- The second method is physical removal. Many folks don’t have a Chinese Tallow in their yard, but either their neighbors do, or the natural area next door does. In this situation, about the best one can do is continually pull up the seedlings once they sprout. If a larger specimen in present, cut it down as close to the ground as possible. This will make herbicide application and/or mowing easier.

- The best option in many cases is use of chemical herbicides. Both foliar (spraying green foliage on smaller saplings) and basal bark applications (applying a herbicide/oil mixture all the way around the bottom 15” of the trunk. Useful on larger trees or saplings in areas where it isn’t feasible to spray leaves) are effective. I’ve had good experiences with both methods. For small trees, foliar applications are highly effective and easy. But, if the tree is taller than an average person, use the basal bark method. It is also very effective and much less likely to have negative consequences like off-target herbicide drift and applicator exposure. Finally, when browsing the herbicide aisle garden centers and farm stores, look for products containing the active ingredient Triclopyr, the main chemical in brands like Garlon, Brushtox, and other “brush/tree & stump killers”. Mix at label rates for control.

Despite its attractiveness, Chinese Tallow is an insidious invader that has no place in either landscapes or natural areas. But with a little persistence and a quality control plan, you can rid your property of Chinese Tallow! For more information about invasive plant management and other agricultural topics, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office!

References:

Langeland, K.A, and S. F. Enloe. 2018. Natural Area Weeds: Chinese Tallow (Sapium sebiferum L.). Publication #SS-AGR-45. Printer friendly PDF version: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG14800.pdf

by Carrie Stevenson | May 8, 2020

In ecology, a “keystone” species is as crucial to an ecosystem as the central stone in this arch.

In architecture, a “keystone” is the top, central block in an arch structure, the one that holds the entire building up. Without it, the bricks around it collapse. With it, there is nothing stronger.

So, when you hear an animal referred to as a “keystone” species, it should get your attention—especially when that species is listed as threatened by state and federal wildlife agencies. In northwest Florida, one of the species upon which the entire longleaf ecosystem is built is the humble gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).

Gopher tortoises are long-lived, protected by their thick shells and deep burrows. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Once hunted for food and currently in competition with humans for buildable land, this long-lived reptile is an architect in its own right. The tortoises are called “gophers” because of their tunnel building and burrow construction expertise. The tortoises spend about 80% of their time near their burrows, of which they have multiple over their lifetimes. Being a cold-blooded reptile, the burrows allow the tortoises a place to live in the temperature-regulated soil.

The average adult gopher tortoise is about 9-11 inches long, although they can be larger. They have thick feet resembling those of an elephant, and scaly front legs used for digging and burrowing. They are tan, brown, or gray, and live in dry, sandy, upland habitats. Their propensity for dry forestland is typically why their populations are in peril, as this is also the best land for building and development.

The average gopher tortoise’s burrow is 6.5 feet deep and 15-40 feet long, and provides habitat for 350 other species! Those commensal species that share its burrow are mostly invertebrates, but at least 50 are larger backboned species like frogs, snakes, rabbits, and burrowing owls. During forest fires, there are stories of multiple species—from deer and snakes and turtles—calling a truce and hiding in the burrows together until the flames blow over.

Gopher tortoises are nesting right now–be sure to observe from a distance!

Right now—from May to July—is nesting season for gopher tortoises. They lay eggs in the soft sand of their burrow apron, which is the triangular spread of loose sand at the opening of the burrow. Eggs incubate all summer and emerge between August and November. The newly hatched tortoises can expect to live 40 to 60 years in the wild. They live on a variety of grasses and low-growing plants native to longleaf pine, oak forests, and coastal dunes, including wiregrass and gopher apple. They are adapted to routine fires, as they are safe in their burrows and the new growth after a burn provides an abundance of their grassy food sources.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 10, 2019

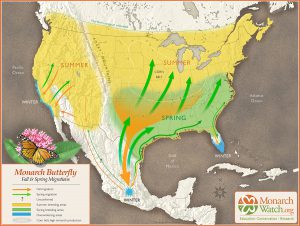

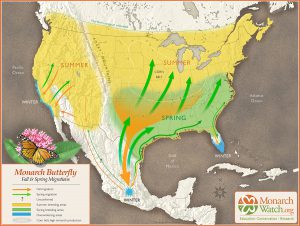

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

This spring, scientists from World Wildlife Fund Mexico estimated the population size of the overwintering Monarchs to be 6.05 hectacres of trees covered in orange. As the weather warmed, the butterflies headed north towards Canada (about three weeks early). It’s an impressive 2,000 mile adventure for an animal weighing less than 1 gram. Those butterflies west of the Rocky Mountains headed up California; while the eastern insects traveled over the “corn belt” and into New England. When August brought cooler days, all the Monarchs headed back south.

What the 2018 Monarch Watch data revealed was alarming. The returning eastern Monarch butterfly population had increased by 144 percent, the highest count since 2006. But, the count still represented a decline of  90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

Scientists estimate that 6 hectacres is the threshold to be out of the immediate danger of migratory collapse. To put things in scale: A single winter storm in January 2002 killed an estimated 500 million Monarchs in their Mexico home. However, with recent changes on the status of the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has delayed its decision until December 2020. One more year of data may be helpful to monarch conservation efforts.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

There is something more you can do to increase the success of the butterflies along their migratory path – plant more Milkweed (Asclepias spp.). It’s the only plant the Monarch caterpillar will eat. When they leave their hibernation in Mexico around February or March, the adults must find Milkweed all along the path to Canada in order to lay their eggs. Butterflies only live two to six weeks. They must mate and lay eggs along the way in order for the population to continue its flight. Each generation must have Milkweed about every 700 miles. Check with the local nurseries for plants. Though orange is the most common native species, Milkweed comes in many colors and leaf shapes.