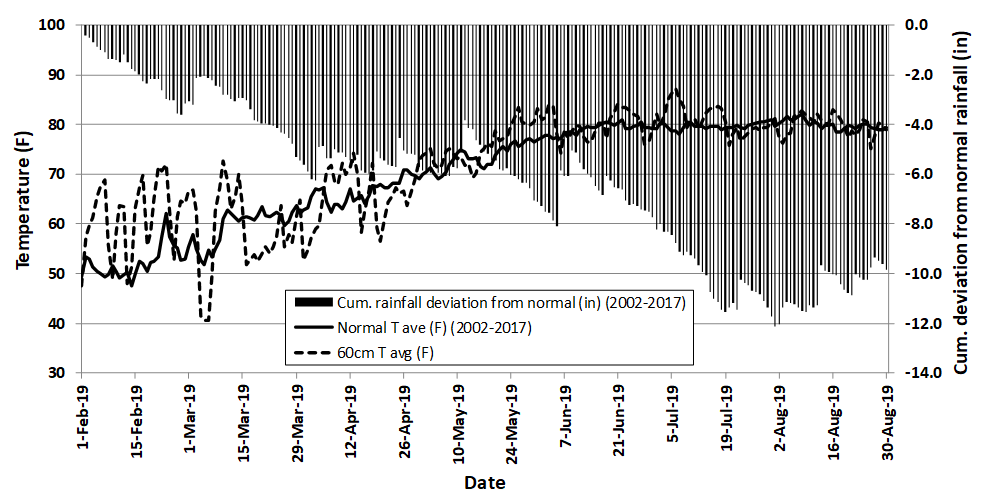

Irrigation is expensive. And there are a lot of non-irrigated or “dryland” acres across the Panhandle. 2019 was characterized by persistent drought stress for much of the season (see below). So in a dry year like 2019, what are you supposed to do to manage soil moisture if you can’t install more irrigation?

Lack of soil moisture leads to a lot of problems. Yield limitations immediately come to mind. I’ve already described the potassium problems associated with lack of soil moisture in the article, “Avoiding Potassium Deficiency in Cotton.” And with potassium deficiency comes increased risk of stemphylium. I don’t need to tell you all the problems associated with lack of soil moisture. It’s something we think is very expensive to manage, so we take our risks growing rain-fed crops instead.

Why would cover crops help with soil moisture status later in the year? Because much of the soil moisture you lose is due to evaporation. If we can reduce the “evapo-” part of the “evapotranspiration equation” by keeping the soil covered with mulch, we should improve soil moisture compared to bare ground.

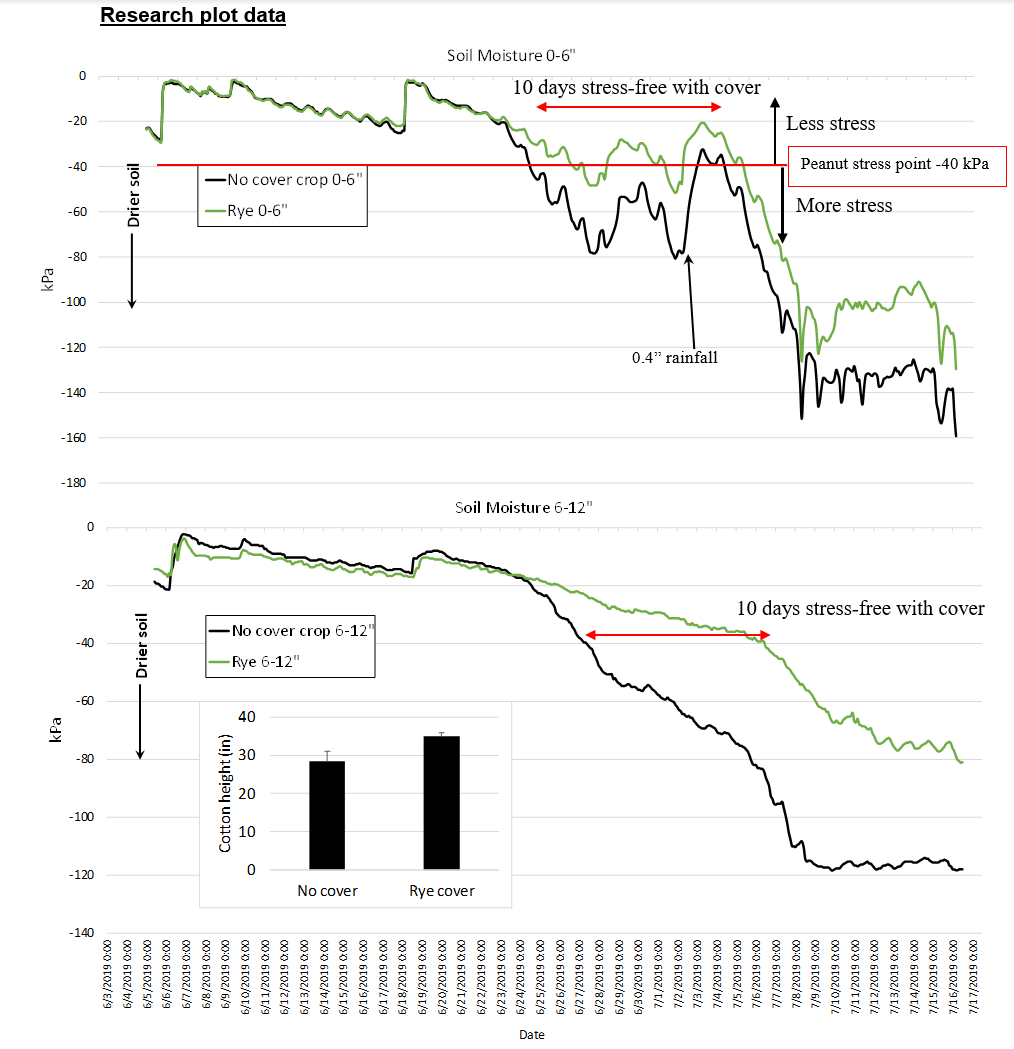

Suppose the soil moisture stress point for peanut is -40 kPa. (This is a good starting point, but might differ for your specific soil.) Looking at the figure below, having a rye cover bought us about 10 days of relatively stress-free time for our crop, compared to having no cover crop, at both 0-6 inch and 6-12 inch depths. (These data are from replicated field trials in Jay, FL.) If this happens several times in the season, the reduced stress really adds up.

Can having a cover crop actually reduce soil moisture in some cases?

The concern here is during the early season after planting the subsequent crop. If the cover crop was terminated shortly before planting the main crop, and the cover crop was still transpiring, it could pull more soil moisture from the ground, leaving less soil moisture for germinating seeds. This is partly why researchers recommend (in Southeast) terminating cover crops around 3 weeks before planting. The reason for this is two-fold:

- It allows some time for rainfall to replenish any lost soil moisture. A single rain event will often replenish soil moisture to levels at or above those with no cover. Added to that, the increased infiltration due to cover crops means more of that rainfall will be “banked” in your soil profile for later use by the main crop.

- A leaching rainfall is desired to wash allelopathic compounds out of the seedling rooting zone. That’s why you want to terminate your cover crop early enough to allow for a rainfall event, as well as allowing the cover crop to dry down enough to be cut by coulters without pinning.

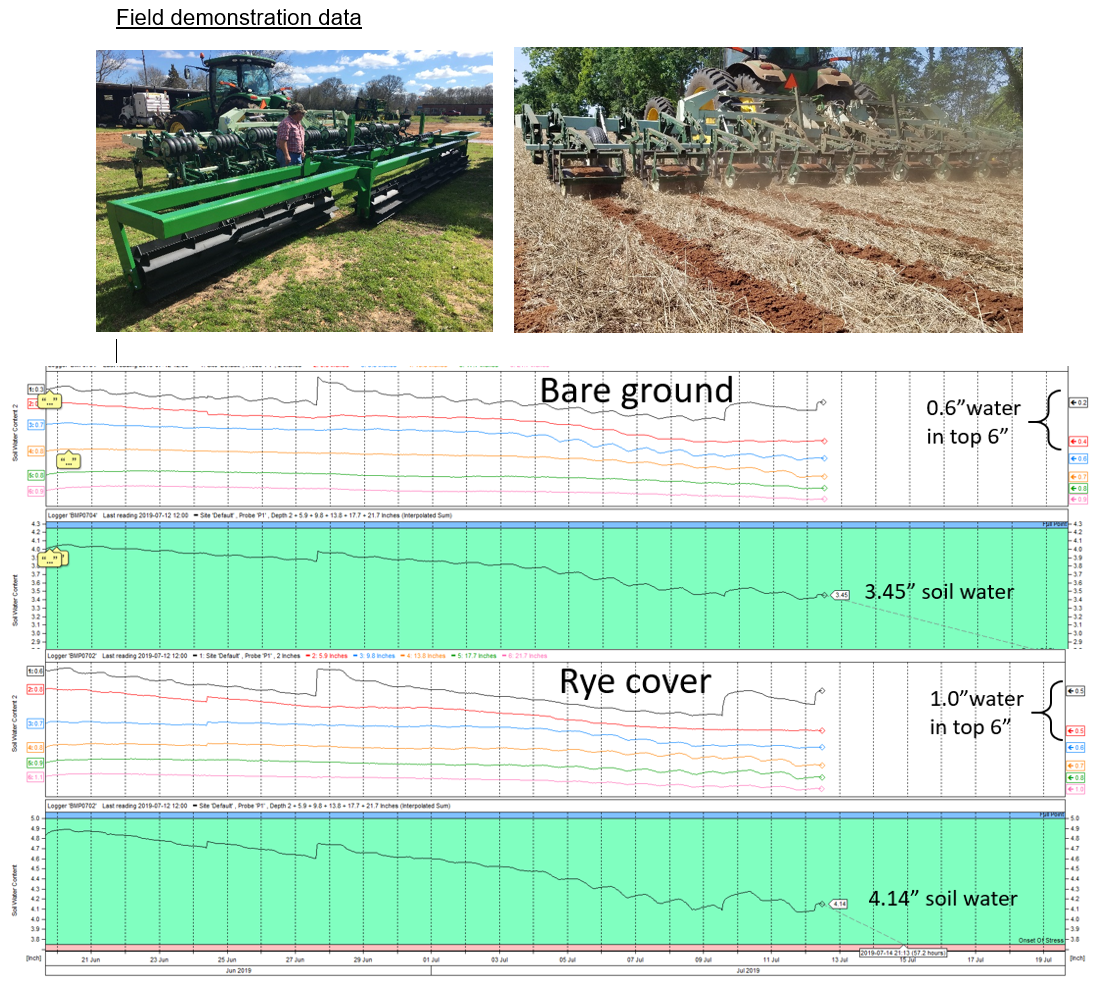

On-farm demonstration data are shown below. In this demonstration, the farmer had 4.14 inches of soil moisture in the profile where a rye cover crop was grown, compared to 3.45 inches without a cover crop. In the top 6 inches, bare ground had only 0.6 inches of water while the cover cropped soil had 1.0 inches to the same depth. Although these observations are shown for July 13, 2019, the date of observation doesn’t really matter since the results are consistent any time there was a concern about a soil moisture deficit. In this case, this farmer reported 100 lbs more lint per acre on the cover cropped ground as compared to grown on bare ground.

So the next time you think you consider irrigation but decide it is too expensive, consider cover crops. If you need incentivization, there may be cost-share programs in the near future to defray the costs of planting and maintaining cover crops. Although as of this writing, cover crop cost-share is limited, check with your Soil & Water Management District for details about cover crop cost-share opportunities in the future. In the meantime, you can experiment. Here are some ideas:

- Drill in a few passes and see what happens as an inexpensive option. Or drill in a field and leave a few passes out. That will let you see the comparisons on your field. (And consider letting me know if you do this, we may collect some data with your permission.)

- Experiment with cover crop mixes. Future cost share programs are likely to require mixes of at least 2 species. Oat and rye are common for that purpose.

- Play with nitrogen (N) rates on the cover crop. A cover crop that doesn’t produce sufficient biomass to cover the soil won’t protect it from evaporation. On the other hand, too much biomass can get in the way during planting. Again, I recommend spreading N at a couple different rates within the same field to get a good idea of how much N you’ll need to apply in the future.

- Four Early-Season Lessons from 2020 Peanut Production - April 9, 2021

- Sprayer Calibration Tables – Calibration Made Easy - October 30, 2020

- Stand Issues – Should You Replant Your Peanut Field? - May 15, 2020