Source: Southeast Innovative Farming Team

Tropical Pacific Heating up

Over the past several months, water temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean have been warming at an alarming rate, building one of the strongest El Niño’s in decades. El Niño refers to the appearance of unusually warm water along the equator from the coast of South America to the central Pacific that occurs every 2 to 7 years. Though commonly measured by sea surface temperatures, El Niño is actually a coupled ocean-atmospheric phenomenon that disrupts climate and weather patterns around the world.

Every El Niño differs in the timing of its evolution and the eventual strength, but this year’s El Niño has come on earlier and stronger than any recorded since 1950. Sea surface temperatures in the monitoring region soared to 2.2 degrees Celsius warmer than normal in August, a record for the month. The all-time record is 2.7 in November of 1997 during the strongest El Niño of this century. Forecasting centers around the world predict the current event to continue building in the next few months and it could approach the strength of the 1997/1998 and 1982/1983 events. It is virtually certain that this El Niño will affect our weather patterns through the spring of next year.

Already Seeing Impacts

One unique feature of the current El Niño is how early in the year it formed. The usual life cycle begins with ocean temperatures starting to warm in the mid to late summer, and then reaching El Niño thresholds (greater than 0.5 C warmer than normal) in the fall and peak strength in the winter months. The current event marked 1.0 C warmer than normal (double the 0.5 C threshold) in April and the warming has not slowed since.

The warm ocean surface triggered the flooding rains in Texas and Oklahoma in May of this year, with satellite images showing a clear connection between the warmth and moisture in the tropical Pacific and the abundant atmospheric moisture during the flood events. Texas and Oklahoma recorded their wettest month ever in May 2015, as did the contiguous U.S. as a whole.

Even with the flurry from Danny, Erika, and Fred in the last two weeks, the Atlantic hurricane season is unusually quiet this year, as was forecast. El Niño creates an environment of unfavorable vertical shear (winds changing with height) that tears apart tropical systems before they can take form and strengthen. Different measures show vertical shear at unprecedentedly high levels over the Atlantic and Caribbean for most of this summer.

El Niño also ushered in warm and dry conditions across much of the Southeast United States in the second half of summer. Though El Niño is not usually much of a player in our summer weather patterns, similar strong and early forming events brought late summer dryness in the past. The west coast of Florida is a glaring exception, where persistent westerly, moist flow caused one of the rainiest July-August on record for Tampa (28.31 inches) and surrounding areas.

Major Shifts in Fall and Winter

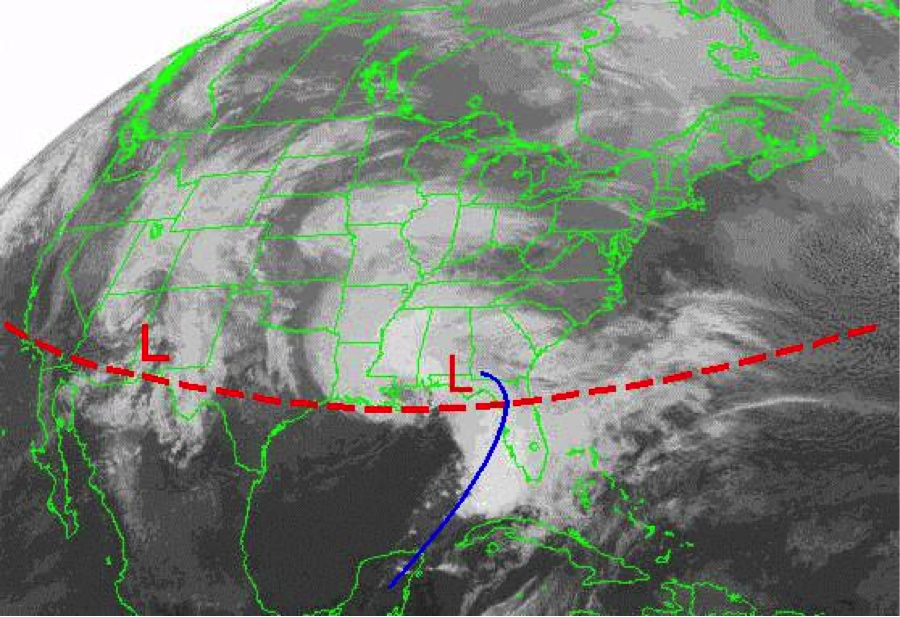

While El Niño is already impacting summer patterns in the Southeast, more profound and predictable changes are on the horizon for the region as fall and winter approach. With the changing of the seasons, the jet streams over North America begin their yearly migration south and become more of a player in the passage of weather systems (like low pressure storms, cold fronts) from week to week. El Niño modifies the usual jet stream patterns and favors a strong subtropical jet that steers frequent winter storms, drenching rains, and cooler temperatures over the northern Gulf Coast and peninsula of Florida. The frequent rains usually commence around November and persist throughout the winter and into the month of March. However, the onset of the El Niño rains is hard to predict and can begin as early as the first week of October, as happened in 2009.

How Much Rainfall?

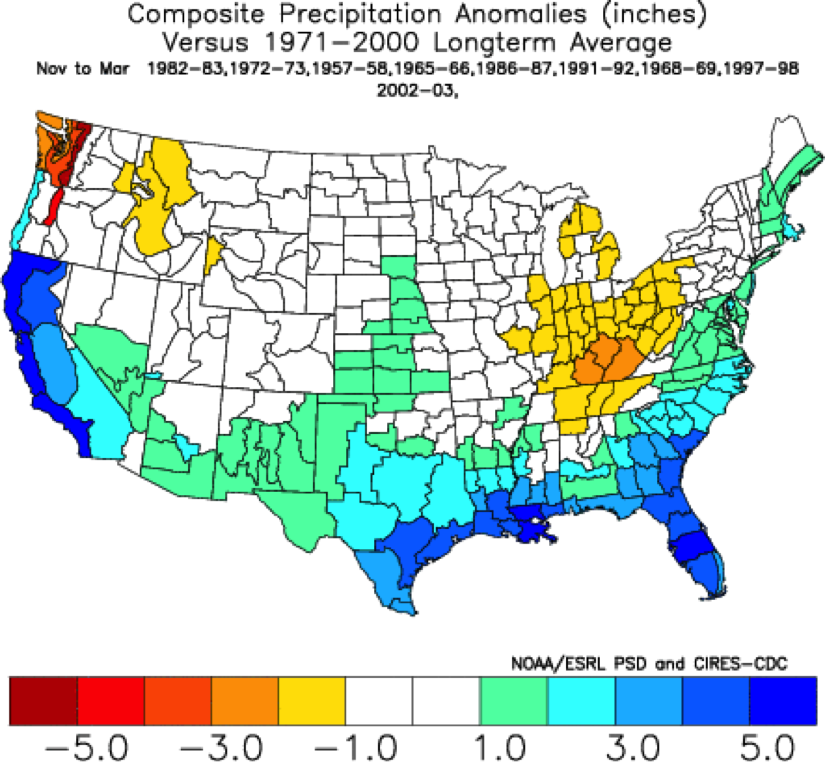

Predicting the exact amount of rainfall and the timing is much more difficult than the general winter trend. The pattern of an active subtropical jet will come and go throughout the winter months, so periods of more or less “normal” weather will be interspersed with periods of recurring winter storms and heavy rainfall. For the winter as a whole, Florida’s dry season will be impacted the most with expected rainfall totals nearly doubling normal. The northern Gulf coast, including Southern Alabama and Georgia, should see a more modest increase of 10%-30%, partly because normal winter rainfall is much greater than peninsular Florida. One common misconception, a “super” El Niño does not necessarily mean that much more rainfall than a moderate one, just a greater confidence the overall pattern will repeat. However, 1997/98 (November-March) did bring record rain totals to the Southeast and Florida in particular.

Severe Weather a Threat – A more southerly storm track and the subtropical jet stream enhancing upper level winds means a more favorable environment for severe weather and deadly tornado outbreaks across the Florida peninsula. Winter is the preferred season for stronger and long-path tornadoes here and studies have shown that El Niño can enhance the threat. Both of Florida’s deadliest tornado outbreaks happened during El Nino, February 1997 killing 42 and February 2007 killing 21.

Coping With El Niño

Knowing there is a very confident prediction for increased storminess and rain across the Southeast, citizens, industry, and government agencies can plan ahead and react accordingly. Parts of South Florida are experiencing severe and extreme drought according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, related to the Caribbean drought brought by El Niño. Rainfall deficits in some areas are among the driest on record for the rainy season (late May – September). It is usually difficult to make up for a poor rainy season during the following winter dry period, but El Niño years can be the exception. Water managers at the South Florida Water Management District can anticipate easing drought conditions this winter and unusually high water levels in Lake Okeechobee going into next summer’s rainy season.

Tampa and the Florida west coast have been inundated with rainfall over the past two to three months. Tampa tied a record for rainiest July and August with 28.31 inches in the two months. Volunteer reporting stations measured as much as 50 inches since June 1st. Rivers, streams, and other surface water are all very high right now, giving utilities like Tampa Bay Water plentiful supplies and many options on where to draw from. A normally dry fall season should bring water levels down some, but the anticipated rainy winter will ensure abundant water supplies for the foreseeable future.

Farming interests like the winter vegetable industry in South Florida and the strawberry region around Plant city will have more problems with disease and fungus with the abnormally wet conditions, and farmers should anticipate needing more applications of fungicide.

El Niño is a great opportunity for cattle ranchers, as a moist and cool winter is favorable for planted winter forage such as rye.

Further north, row crop farmers in the Tri-State Wiregrass region will have to deal with frequent rainfall hampering harvest operations. Cotton, peanuts, and soybeans are some of the primary crops here and they need to be harvested in the fall of the year. Even more challenging is finding good weather windows to dry dug peanuts and defoliate cotton fields. September and October normally bring the driest weather of the year to this region, so it is imperative harvest progresses as quickly as possible during good weather windows before the frequent rainfall from El Niño sets in later in October or November.

Following harvest, cover crops should be planted as early as possible to provide erosion protection from the anticipated heavy rainfall events.

As winter transitions into spring, cover crops can be left growing longer to accumulate biomass and to remove excess soil moisture through evapotranspiration. Early planting of corn in the first week of March may be delayed with the predicted abnormal rainfall, and cloudy skies and cooler temperatures may delay growth.

Additional Resources:

For a detailed discussion of the current and predicted state of the Pacific Ocean, see NOAA’s El Niño advisory:

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory/ensodisc.html

For local impacts of El Niño at weather stations near you, use the “climate risk tool” at AgroClimate.org: http://agroclimate.org/tools/climate-risk/

For basics on El Niño and agriculture, see also AgroClimate.org: http://agroclimate.org/fact-sheets-climate.php

- November 2025 Weather Summary & Winter Outlook - December 5, 2025

- Friday Feature: The History of Beekeeping - December 5, 2025

- Friday Feature:Malone Pecan Festival Tractorcade - November 21, 2025