Yield is what is typically evaluated when you consider hay production efficiency, but the forage quality also plays a huge role, because it determines the amount of supplemental feed that must be purchased to maintain animal performance. Photo credit: Doug Mayo

As cattle prices have drastically declined, producers are closely examining every production expense. It makes perfect sense to closely evaluate the efficiency of the hay produced on an operation, because hay is typically the most expensive feed fed to livestock. Not only because of the cost to produce it, but because of the sheer volume needed as the base feed when summer pastures are dormant.

Yield is what is typically evaluated when you consider efficiency, but the forage quality also plays a huge role, because it determines the amount of supplemental feed that must be purchased to maintain animal performance. Producers often focus on the protein provided by forages, but the biggest challenge to maintaining the body condition of cattle through the winter for growth, reproduction, and milk production relates to fiber digestibility and ultimately the level of energy provided by the hay. In cattle production the energy content of feedstuffs are usually measured as Total Digestible Nutrients (TDN). In essence then the goal should be to produce the optimum level of both yield and quality measured, not in total pounds of hay, but in total pounds of TDN/acre. As you drill-in on hay production, there are four key areas of management that impact overall efficiency.

1 Variety Selection

There are clear differences between forage types as to both the yield and quality of hay produced. In general, legumes and annual forages have the highest quality, while perennial grass varieties provide the greatest yield per acre.

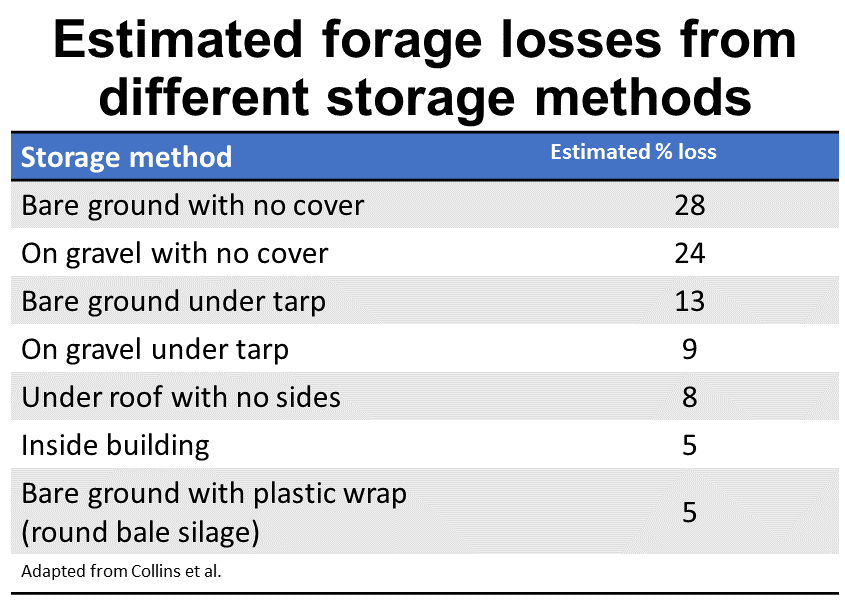

Summary of 16,000 forage samples submitted to the University of Georgia’s Feed and Environmental Water Lab between July 2003 and February 2011. The average (black vertical lines) and typical range (yellow to green horizontal bars) RFQ Scores for samples of various forage species submitted. Behind the graph lies a gray bar representing the RFQ requirements for dry cows and a blue bar for the RFQ requirements for lactating beef cows. Source: Forage Quality Differences in Species.

In the early 2000s, researchers from the University of Wisconsin and the University of Florida developed a more robust measure of forage quality called Relative Forage Quality (RFQ). The RFQ index is based on TDN and and fiber digestibility as well as estimates of dry matter intake (DMI) . In the chart above you can see the variation in Relative Forage Qulaity (RFQ) of different forages. Just as cattle producers have learned to depend on indexes such as $Weaned or $Beef for cattle selection, the RFQ scores provide a single index number that accounts for the total nutrient quality and digestibility that affects both voluntary intake and nutrient availability. An RFQ score of 100 meets the nutritional needs of dry, mature cows. In the Chart above the black bars are the averages for the listed forage varieties. It is clear that alfalfa, perennial peanut and traditional peanut hay are superior for RFQ. There are other annual varieties however, such as small grains, and ryegrass that can also meet the needs of lactating cattle. Notice that the higher quality pearl millet and sorghum samples sent into the Forage Lab met the energy requirements of lactating cattle as well. In years when weather conditions favor annual forage production, excess growth can be harvested for excellent quality baleage or hay.

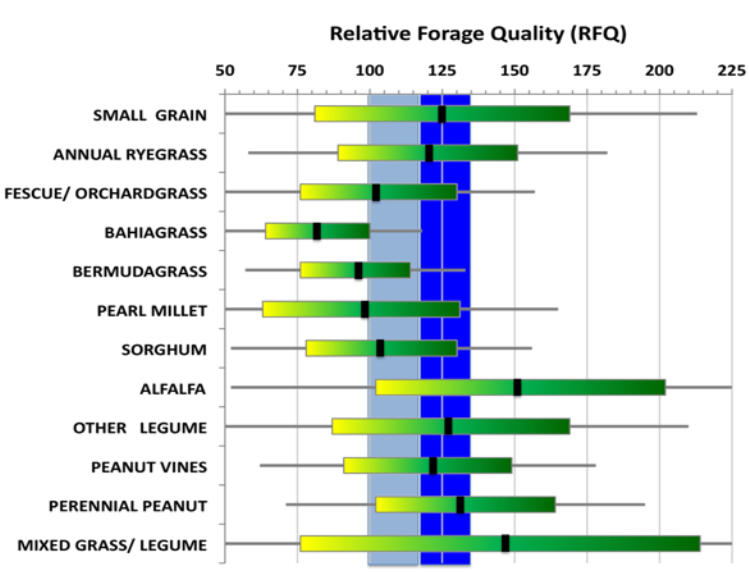

Legumes, however, are generally no match to the yield of perennial grasses. Most legumes will only produce 2-5 tons of forage per acre in a season.The table above shows how much forage can be produced with high fertility at the research station in Tifton, GA. Researchers there produced an average of 6-12 tons of forage with Bahia and Bermudagrass Varieties in their 3-year variety test, which is not really the same as large scale commercial hay production. The key point of this chart, however, is that when all varieties were managed equally, the newer grass culitivars produced superior yields as compared to the old standards of Pensacola and Coastal.

Legumes, however, are generally no match to the yield of perennial grasses. Most legumes will only produce 2-5 tons of forage per acre in a season.The table above shows how much forage can be produced with high fertility at the research station in Tifton, GA. Researchers there produced an average of 6-12 tons of forage with Bahia and Bermudagrass Varieties in their 3-year variety test, which is not really the same as large scale commercial hay production. The key point of this chart, however, is that when all varieties were managed equally, the newer grass culitivars produced superior yields as compared to the old standards of Pensacola and Coastal.

As you can see, there are a number of forage variety options to choose from to efficiently produce quality hay for cattle. On most operations, however, the hay fields have already been established, so the remaining three areas of management should be the focus for improving the efficiency of fields already in production.

2 Production Management

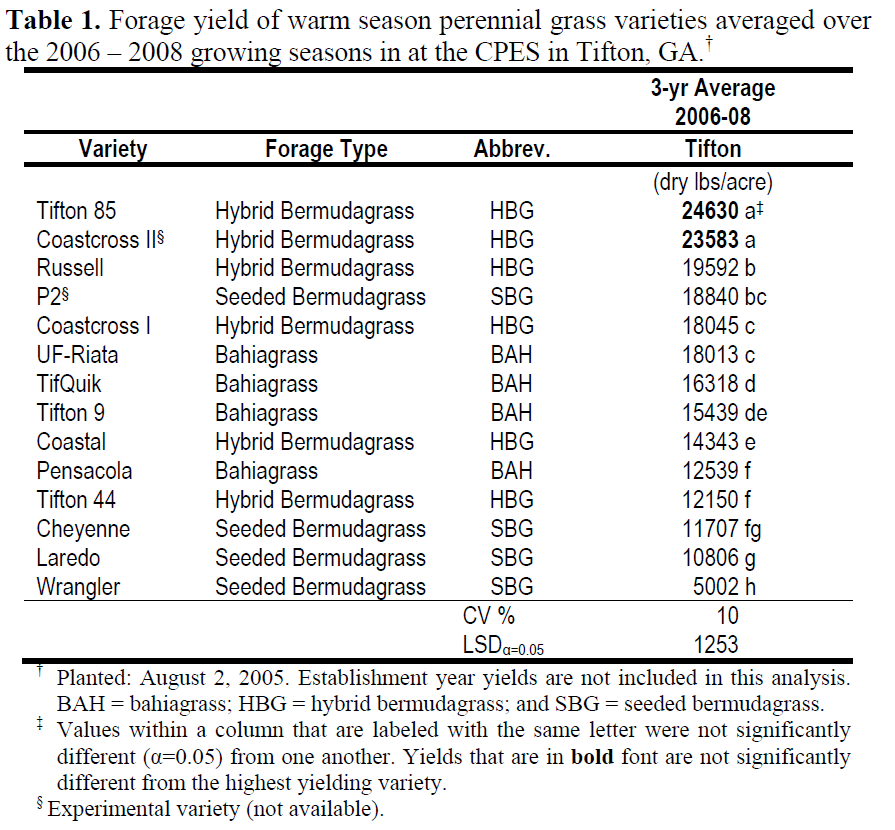

Source: Bermuda Grasses in Georgia

Fertilization is the primary management tool used to boost hay production. The chart above illustrates the level of nutrients removed from a 6-ton hay harvest season. When it comes to fertilization, “Nitrogen is the gas that makes grass grow.” Nitrogen has the greatest impact on the growth and total yield of forages. The other three elements are still very important for the health and long-term productivity of a hay field.

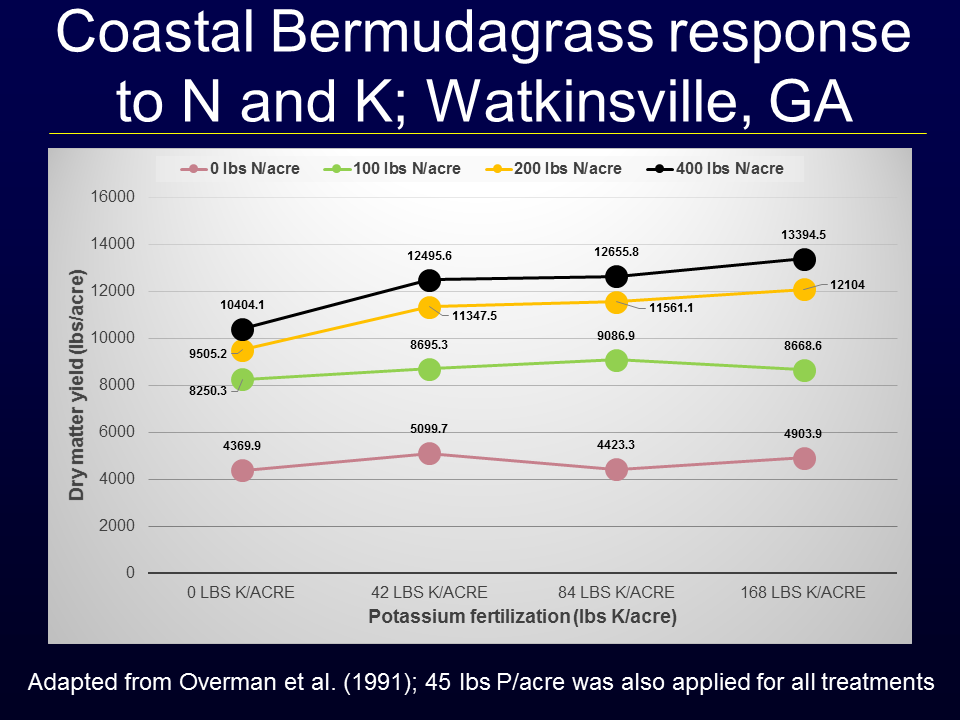

Source: Improving Pasture Efficiency

During his presentation on Improving Pasture Efficiency at the 2015 Northwest Florida Beef Conference, Jose Dubeux shared the results of some research on the effects of both nitrogen and potassium fertilization of Bermudagrass in Georgia. In this study, 100 pounds of nitrogen doubled the Coastal Bermudagrass yield, but there were diminishing returns for nitrogen fertilization beyond that point. The potassium that research has shown is so important for health of the stand, had a much smaller effect on total forage yields.

Don’t forget to pull soil samples annually to make sure the pH of the field is in an acceptable range to get full use of the fertilizer that is applied, and that only the phosphorus, potassium and sulfur that are needed by the crop are applied. These nutrients are essential for stand health and maintenance, but will only enhance yields if they are deficient. The small investment in soil testing ensures the most efficient use of expensive fertilizers.

The other key area of production management is pest management. With lower cattle prices, it may be tempting to skimp on the costs for weed and armyworm control, but these pests rob hay fields of both yield and quality. Weeds steal water and nutrients, and armyworms consume the most nutritious parts of the plant – the leaves. The way to control pests more efficiently is to scout hay fields more frequently and control them when they’re small and easier to control with cheaper chemicals.

3 Harvest Management

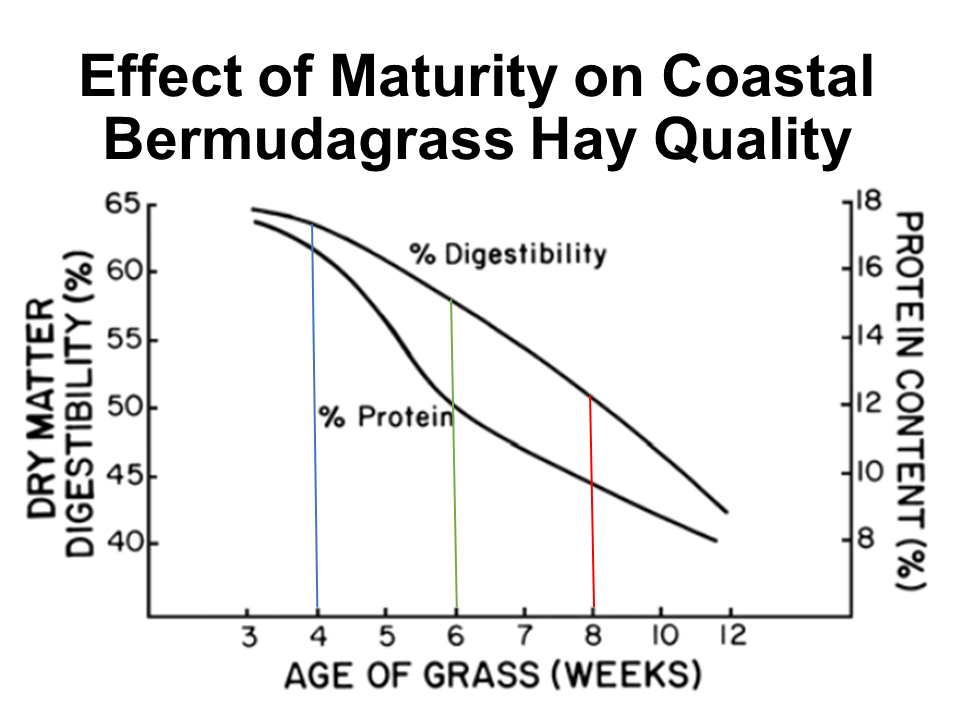

Source: Bermuda Grasses in Georgia

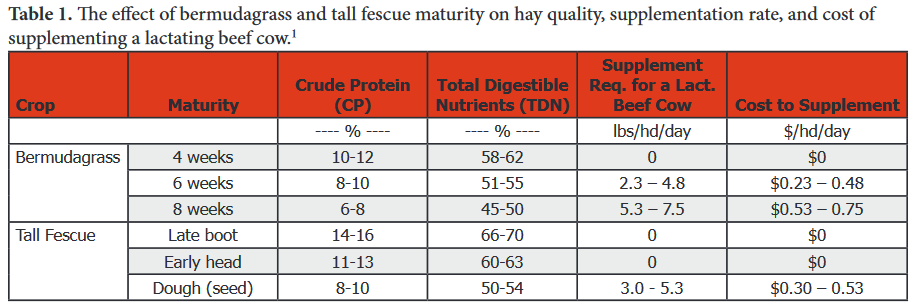

No matter which forage variety you choose to harvest for hay, or the level of nitrogen fertilization utilized, maturity has the greatest effect on the digestibility and ultimately the level of energy available to livestock. At six weeks of growth or re-growth, Coastal Bermudagrass has a 3% higher protein concentration and is 10% more digestible than at eight weeks re-growth. While that may not sound like that big of a difference, the cost of purchasing supplemental feeds can add up quickly.

Assumptions: 1,200 lb beef cow, average to above-average milking ability, first three months postpartum, 6.0 lbs of TDN required daily, and supplement that provides 85% TDN and costs $200/ton ($0.10/lb). Source: Understanding and Improving Forage Quality

The data in the chart above, with an assumed $200/ton supplemental feed, shows a significant difference in hay quality based solely on when it was harvested. The 6-week old bermudagrass grass was high enough in quality that only 3.5 pounds of daily supplemental feed would be needed to maintain a cow nursing a calf during peak lactation. The 8-week old grass would require 6.5 lbs./day/head of supplement. The three pound/head difference may not sound like a big deal, but when you do the math for a 100 head herd being fed for 120 days it equals an additional 18 tons of feed, which in this example, is an added $3600 expense. The only difference in how it was managed was how mature the hay was when it was harvested. True the older grass would produce higher yields, so it is somewhat of a balancing act to harvest immature hay that is old enough for adequate yield. As a general rule, 5-6 week old hay provides a good balance for both. Certainly, rainfall plays a major factor on the timing of harvest, but in general the goal should be to harvest before the grass becomes rank with seed heads and much lower digestibility. Harvesting more frequently will increase harvest costs, but it will also spread your risk from losses due to unexpected rainfall and armyworms.

There are other factors in addition to maturity that affect forage quality, so it is important to send in forage samples for lab analysis before developing your winter supplementation plan. While your at it, enter that quality hay you have produced in the Southeast Hay Contest, so you can get the forage analysis you need and potentially earn some bragging rights as one of the best hay producers in the region.

4 Storage Options

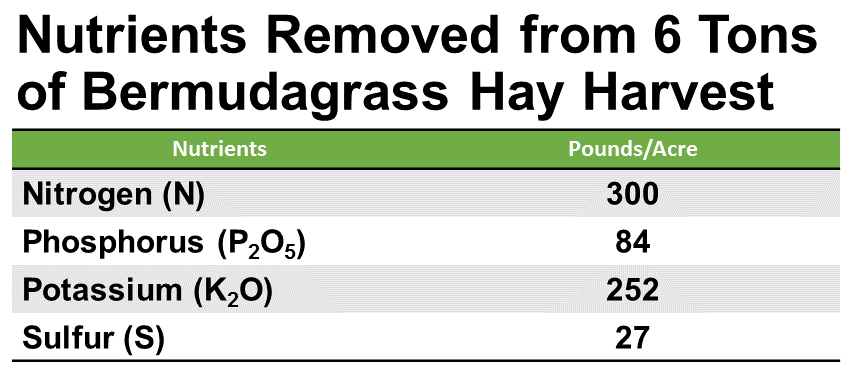

The final challenge is protecting this valuable resource you worked so hard to produce. You can do everything right: best forage variety, fertilizer, weed control, and harvest date, and still be inefficient, if hay is left outside in the weather for 6-9 months. As the chart above indicates, hay stored on the ground, and out in the elements deteriorates by 28%. Put another way, you could get by producing almost 25% less hay each year, if you store it under a barn.

There are other tricks to the art of hay making that can also improve efficiency, such as the type of equipment used, managing the moisture content, and weather forecasting abilities. If you make the effort and investment in a productive forage variety, fertilize it well, keep the weeds and pest to a minimum, harvest before maturity, and protect it during storage, you can produce a consistent, quality feed for your herd year after year. The management techniques described in this article are not the cheapest methods to produce hay, but if you compare the digestible nutrients produced to the investment made, it will be more efficient.

- 2025 Weather Summary and 2026 1st Quarter Outlook - January 16, 2026

- 2025 Average Farmland Rental Rates, Lease Agreements, and Worker Wages Summary - January 16, 2026

- Friday Feature:1954 How to Dial Your Phone - January 16, 2026