Kelly Racette, Diane Rowland and Barry Tillman, UF/IFAS Agronomy Department

For as long as crops have been domesticated, farmers have been selecting seed from the best performing plants; based primarily on their yield and relative performance. In some cases, a plant may experience stress during the season, whether from disease, drought, or insects. Many times that plant will recover and still produce a decent yield, and possibly provide seed for planting the following year. It’s a system that has worked relatively well for a long time. But this system depends on the idea that if a plant experiences stress and survives, it won’t pass a memory of the stress on to its offspring. Farmers and researchers have made the assumption that the impacts of stress on a plant remain in the current generation and don’t make an imprint into the next generation. But recent research suggests that this might not be true.

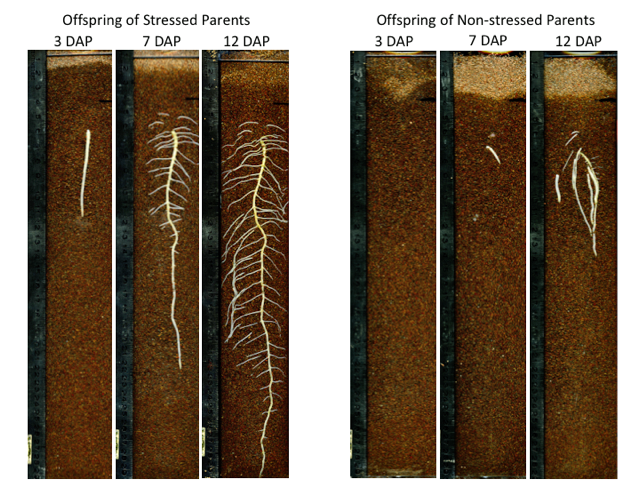

Several studies of seed quality, seedling development, and vigor conducted by researchers at the University of Florida suggest that a “memory” of stress events in plants can be passed on to the next generation. In these studies, some varieties of peanut, for example, TUFRunner ‘511’TM, showed an increased rate of establishment and root growth when their parents had experienced a mild water stress, even when the next-generation seedlings themselves were well-watered (Figure 1). However, other varieties (C7616) displayed the opposite trend; seedlings had improved establishment and root growth when their parents had been well-watered. To complicate matters even further, a third set of varieties, including the Spanish-type variety, COC041, showed no evidence of stress memory in their offspring at all.

Figure 1: Peanut root bioassay for early germination and root establishment for seed produced from parent plants that had experienced a mild drought stress during the season and for seed from parents that had not experienced any stress. The left hand panel clearly shows faster and more extensive root growth in offspring from stressed parents over a 12 day span (DAP = Days After Planting). Photo credit: Kelly Racette.

The presence of either a positive or negative memory in crop plants could have big implications for seed production. For example, if exposing parent plants to some degree of stress increased seed quality of the next generation, through improved germination and establishment, it may be useful to produce seed under mildly stressful conditions for these varieties. On the other hand, growing varieties that have poor seedling performance from stressed parent plants would require more careful management for seed production to get the best quality seed.

Before recommendations can be refined based on generational stress memory for the production of seed peanuts, further research is being conducted to find out which varieties of peanut display this “memory” and what other impacts stress could have on seed quality. Currently, studies are being done on other Spanish- and runner-type varieties, like FloRun ‘107’TM and New Mexico Valencia C. This additional information is critical to “fine tune” the ideal conditions for each variety during seed production to maximize the quality of seed essential for optimal germination and stand establishment. This research also extends and highlights how important optimal crop management is, because decisions within a season could be impacting the next generation.

- Rapid Response Team Deployed to Investigate Peanut Collapse - September 21, 2018

- Developing a “Stress Breathalyzer” for Peanuts - April 13, 2018

- Peanut Nodule Analysis to Assess Crop Health - August 18, 2017