Picture: UF/IFAS agronomy students dig up peanut plants for a nodule sample at the Suwannee Valley Agricultural Extension Center near Live Oak, FL

David Hensley and Diane Rowland, UF/IFAS Agronomy Department

One of the primary benefits of growing legumes like peanut is their ability to convert nitrogen in the atmosphere to a form that is available for use throughout the plant. They do this by forming a symbiosis (a mutual “partnership”) with bacteria known as Rhizobia. When Rhizobia become associated with peanut roots, the plant and bacteria form a structure known as a nodule that houses the bacteria and creates the most beneficial conditions for the bacteria to thrive. The nodule is also the site where the fixed atmospheric nitrogen is delivered to the plant. Most of a legume’s nitrogen needs are supplied by the Rhizobia in its root nodules, and when nodules degrade either during the season or when the crop is harvested, some of that fixed nitrogen may become available to the following crop. However, one barrier to this process is if nitrogen happens to be high when peanut is planted, either through residual nitrogen left from the previous crop or if nitrogen is added to peanut directly. When nitrogen is high, this tends to decrease the symbiosis with Rhizobia, and thus the formation of nodules.

Current research at the University of Florida (UF/IFAS) is looking at this nodulation process closely, characterizing the different stages of development that nodules pass through. This knowledge may help growers better gauge how the symbiosis between peanut and the bacteria is progressing during the season, as well as estimate the stress level being experienced by the crop. To do this, graduate student David Hensley in the laboratory of Dr. Diane Rowland has been studying closely how nodules initiate, grow and become active, and finally degrade through the course of a season. Using a digital, automatic color image analysis process, David is able to use scanned images of root nodules removed from peanuts to determine the total number and average size of the nodules, and by cutting the nodules open, can determine their internal color. These three traits together are indicative of how effective the symbiosis is between the peanut and Rhizobia and how well the process of fixing nitrogen from the atmosphere is progressing.

Peanut nodules are carefully removed from sampled roots from the field. The nodules in the container will be scanned and dissected.

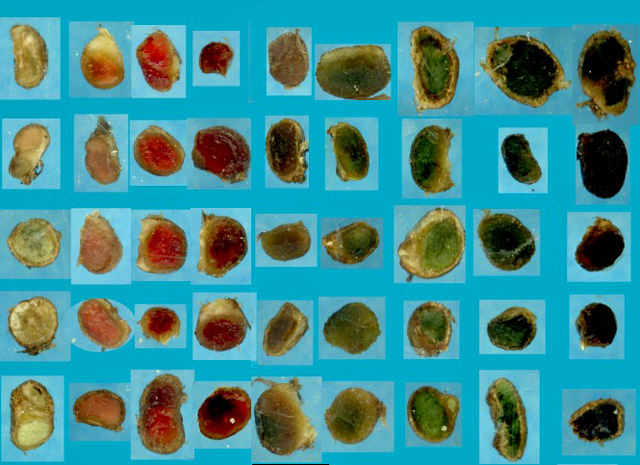

The internal color of the nodule dictates its activity level. Nodules which are deep red in color are active, indicating that conditions are optimal for Rhizobia to perform their nitrogen-fixing function. Nodules with lighter, whitish internal color do not yet (or possibly never will) have active Rhizobia, and greenish nodules have begun to naturally age and will cease to fix nitrogen. Dark, blackish nodules, on the other hand, have begun to decay due to damage or possibly stress. By assessing the relative presence of these colors, the effectiveness of the root nodules can be determined at any point during the growing season.

From left to right, examples of nodule internal color representing not yet active rhizobia, increasingly active, fully active, and darkening to green and black, representing senescence and decay. These individual nodules are only a few millimeters wide, and are taken from scanned images used in UF/IFAS digital color analysis.

This color analysis system, that David Hensley developed, may help growers in determining the overall health of the nodulation of their peanut crop. By assessing the color classes and the number of nodules within each color class, information about how healthy the nodules are in a field can be noted. Nodules respond to stress in the environment by stopping nitrogen fixation, or even by decaying faster than in the best field conditions, so this assessment can give an indication to the grower about the level of stress experienced by the peanut.

This provides growers with one more tool in scouting for stress and diagnosing possible problems the crop may be facing. Ultimately, nodule color may be an early warning system, since this symbiosis is one of the first responders to drought and other crop stresses. These color assessments can help researchers and eventually growers understand these stress conditions, as well as the processes occurring at the end of a nodule’s life cycle. Monitoring these processes, which are crucial to the release of nitrogen from root nodules into the soil, will also help quantify the nitrogen benefits from rotations that include peanuts.

- Rapid Response Team Deployed to Investigate Peanut Collapse - September 21, 2018

- Developing a “Stress Breathalyzer” for Peanuts - April 13, 2018

- Peanut Nodule Analysis to Assess Crop Health - August 18, 2017