Don Shurley, Professor Emeritus of Cotton Economics

Don Shurley, Professor Emeritus of Cotton Economics

Contamination from plastics is a hot-button topic in the US cotton industry right now. It should be. It’s a serious problem. Major culprits include plastic wrap from round modules, shopping bags from stores, and plastic used as ground cover in the production of previous crops in a field.

High quality fiber is one reason foreign mills have beat a path to our door in recent years. As an industry, anything that impacts the demand and market share for our cotton—especially overseas, needs to be resolved. The industry is being vigilant in addressing this problem. Groups have visited foreign mills to observe and discuss the problem. Also, the National Cotton Council will soon roll out an intensive educational effort.

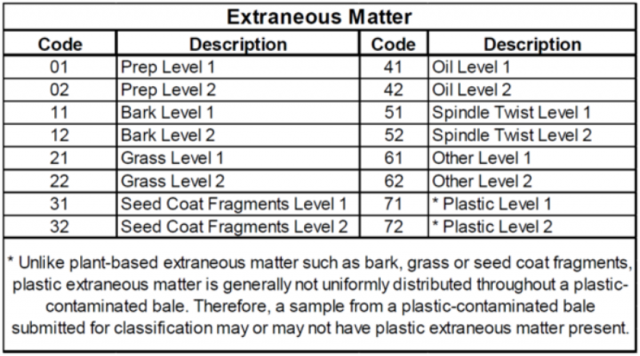

Beginning with this year’s 2018 crop, the USDA-AMS Cotton Program is implementing new extraneous matter codes, 71 and 72, for plastic—“71” means type 7, level 1 (light) and “72” means type 7, level 2 (heavy). Producers will begin to see these new 71 and 72 codes on their bale analysis classing reports, if plastic is detected in the sample. For 2018 loan value purposes, FSA will treat plastic as “Other” (codes 61 and 62). Discounts for plastic are severe. The loan value discount for level 1 is 460 points or 4.6 cents/lb—about $23 per bale. The cash/spot market discount for a level 1 is currently mostly 375 to 550 points or, again, roughly $23 per bale.

For 2018 loan value purposes, FSA will treat plastic as “Other” (codes 61 and 62). Discounts for plastic are severe. The loan value discount for level 1 is 460 points or 4.6 cents/lb—about $23 per bale. The cash/spot market discount for a level 1 is currently mostly 375 to 550 points or, again, roughly $23 per bale.

Prior to this year, any bale sample found to contain plastic was coded as “Other”—a 61 or 62 (see the table above). “Other” could also be anything else not otherwise in the above table. But, now that plastic will have its own code, such a bale may be discounted even more severely. Further, such a bale could be rejected from the market place entirely.

The severity of the plastics problem is not understated. Therefore, an issue for the industry is this—it appears that classing data does not reflect what we feel is the true severity of the problem. If bale sampling and classing were detecting any plastic to a great extent, classing data would show it. If classing doesn’t detect the problem (if there’s plastic in the bale), then coming up with new classing codes wouldn’t necessarily be a solution except to say that if plastic is detected, it will now be coded and better known as such.

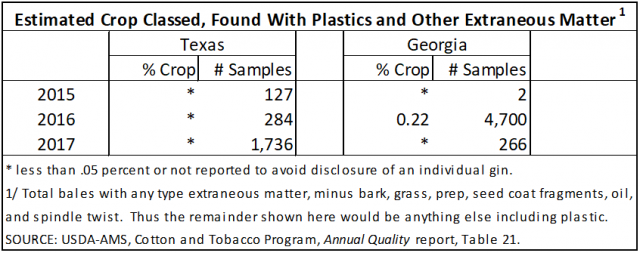

Let’s look back 3 years at both Texas and Georgia classing data as examples. Prior to 2018, if plastic was found in the sample, it was coded as a 61 or 62 and included in the “Other” category. In 2015, ’16, and ’17 if I take the total bales classed that contained extraneous matter of any sort and then subtracted everything but the “Other” category, then by definition the number of remaining samples classed must be the ones with any other type of contamination—plastic plus anything else not accounted for. The numbers in this table would then be the maximum possible number of bales that, when sampled, were found to contain plastic. I am told that in some years, samples actually containing plastic were considerably less than this.

The numbers in this table would then be the maximum possible number of bales that, when sampled, were found to contain plastic. I am told that in some years, samples actually containing plastic were considerably less than this.

For Texas, 2017 was the Hurricane Harvey year and a big jump in 61s and 62s, but still less than 0.05 percent. In Georgia for 2016, 4,700 running bales or 0.22% classed 61 or 62, but it’s believed most of this number was actually due to whitefly damage.

Unlike plant-based extraneous matter, plastic is generally not uniformly distributed in the bale. There may be plastic in the bale, but not in the sample. The plastic may not be realized until that bale gets run in the mill. THIS is the problem. If bales with plastic keep showing up, the mill may avoid that gin or origin all together.

Since classing may not necessarily catch the problem, even with the new coding, the only real solution is that producers and gins must be vigilant to adopt practices to keep plastic out.

—

- 2025 Weather Summary and 2026 1st Quarter Outlook - January 16, 2026

- 2025 Average Farmland Rental Rates, Lease Agreements, and Worker Wages Summary - January 16, 2026

- Friday Feature:1954 How to Dial Your Phone - January 16, 2026