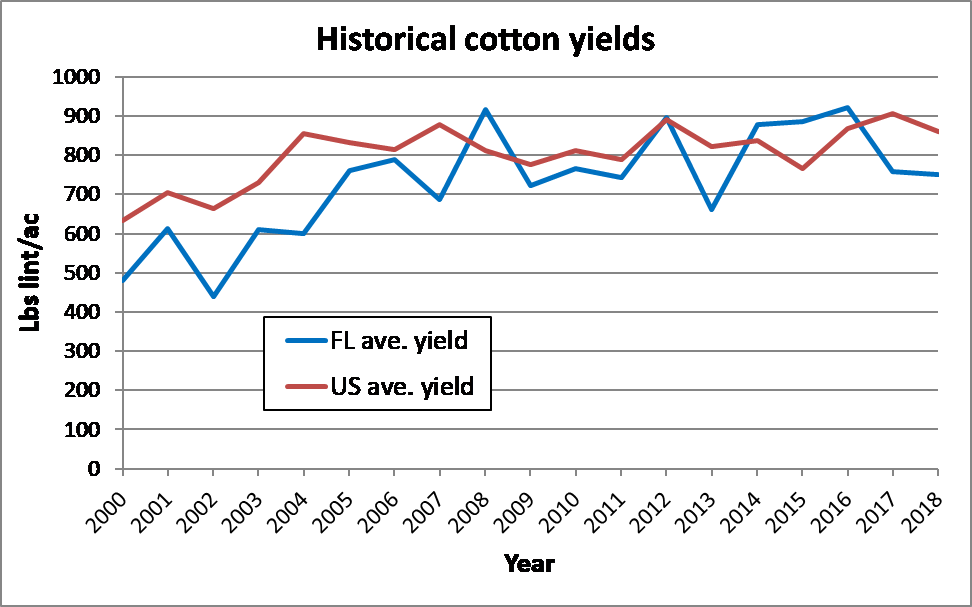

Every year, I see more potassium (K) deficiency in cotton. This isn’t surprising, since yields have increased with modern cultivars and yield expectations (Fig. 1). The bolls we’re asking plants to carry is a lot higher than they used to be. Keep in mind that K is particularly needed during boll set and fiber elongation (along with stomatal regulation and resulting evapotranspiration). In fact, cotton is one of the few crops where demand for K is greater than N.

Figure 1. Average cotton yield in Florida and the US since 2000. In that time, Florida yields have increased 50% from 500 lbs/ac to 750 lbs/ac. Increased demand for nutrients, particularly K, is a result.

Typically, I start getting calls about K problems after boll set, when demand for K is at a peak. During boll set, the bolls are a huge K sink, pulling K from leaves, so this is when you’ll see the biggest problems (Fig. 2). During peak demand at boll formation, K demand can be upwards of 3 lbs K2O per acre per day, so keeping up with this demand is a challenge.

The problem is also common during periods of drought because there is not enough K in soil water for the plant to take it up, even if there is sufficient soil test K. When boll set coincides with drought, big trouble occurs (Fig. 2). Don’t be fooled – just because you are on tight dirt, doesn’t mean you won’t have problems.

Figure 2. Severe K deficiency in cotton. This was from a field in Escambia County, Florida, where the soils have higher clay content, CEC, and moisture holding capacity than many cotton growing areas east of there. This grower applied 70 lbs K2O/ac when his soil tests called for 125 lbs. There is nothing you can do, once you get to this point. Do not shortchange yourself on K in cotton – pay attention to your soil test reports, and understand them.

—

Understand your soil test report

Soil testing labs in the Southeast typically split their recommendations into three (or more) categories: low (L), medium (M), and high (H), as in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Soil tests are split into three (or more) categories: low (L), medium (M), or high (H). The fertilizer recommendation will be the same within a category, regardless of your values being on the high end or low end of a category.

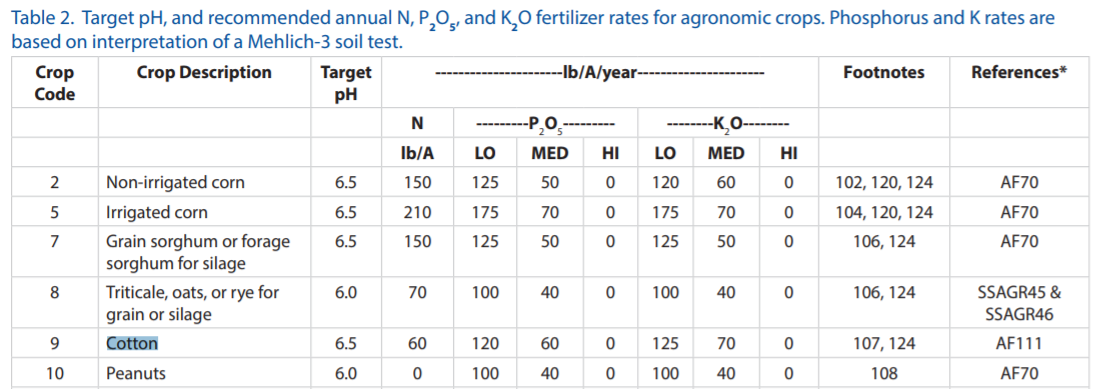

Within any of these, the recommended fertilizer rate is the same. In other words, a soil test showing 0 ppm K will have the same recommendation as one with 25 ppm K (Table 1).

Table 1. Credit: Mylavarapu, R., Wright, D., Kidder, G., 2015. UF/IFAS Standardized Fertilization Recommendations for Agronomic Crops. Nutrient Management of Vegetable and Row Crops Handbook. UF/IFAS, Gainesville, FL, pp. 93-100.

If your test comes back at 25 ppm, the recommendation will be 125 lbs K2O/ac (Table 2). If it comes back just 1 ppm higher (that’s just 2 lbs K2O/ac difference), the recommendation will be 70 lbs K2O/ac.

Credit: Mylavarapu, R., Wright, D., Kidder, G., 2015. UF/IFAS Standardized Fertilization Recommendations for Agronomic Crops. Nutrient Management of Vegetable and Row Crops Handbook. UF/IFAS, Gainesville, FL, pp. 93-100.

As an aside: Why does a soil test difference of 2 lbs/ac (1 ppm) change the recommendation by 55 lbs/ac (70 vs 125 lbs K/ac)? The answer to that is because it’s easier to categorize soil test values into a few recommendations rather than apply an equation for a more precise recommendation, which is probably something that’s been grandfathered in from days before computers were as powerful as they are now. This is probably an area for improvement in our soil testing labs (and something I’d like to work on).

So ask yourself: Am I at the low end of the soil test range or the high end (Figure 3 and Table 1)? If I’m at the high end, I’m probably safe with the K recommendation. If I’m at the low end of the range, I would consider adding more K. (Remember, K doesn’t have the environmental concerns as N and P, so adding some more K comes at a much lower environmental risk than additional N or P.)

—

So what can I do to avoid potassium deficiency in cotton?

- Consider irrigation. Yes, this is expensive, but irrigation solves a lot of problems. More soil moisture means more K in the soil water, so plants can take it up. If you can’t install irrigation, cover crops are even more essential.

- Consider cover cropping. More soil cover means less evaporation from the soil, which conserves soil moisture. For this to work, you’ll need a persistent cover crop with a lot of biomass. Clover or tillage radish won’t persist long enough to protect against soil evaporation in August. (I like rye with 40 lbs N/ac, personally.) Cover crops can be a poor man’s irrigation. And cover cropping is less expensive than irrigation!

- Don’t shortchange your K fertility. Especially on sandy soils, you may need to split your K applications. Look at your soil test report – are you on the low end of the recommended range? If so, consider adding some more.

- Deep K probably won’t work. Getting creative and placing K deep behind a subsoil shank, where soil moisture is greater, probably won’t work. Some colleagues of mine in Alabama tried it. I give them a lot of credit for trying.

- Foliar applications probably won’t work. Peak K demand can be upwards of 3 lbs per acre per day. If you’re in a deficient situation, there’s very little chance that you’ll be able to foliar-apply enough to keep up with demand. You best bet is to avoid this situation – see #1, 2, and 3 above. (That said, foliar nutrient applications are probably good if you’re managing 3+ bale cotton – but that’s another topic for another day.)

- Breeding? If any breeders are reading this, I’d like to take the opportunity to bend your ear. Can we take advantage of early-season luxury K uptake to satisfy late-season K demands? I’ve spoken to one industry breeding program about this, who didn’t say this was a crazy idea. But it could be just that.

- Four Early-Season Lessons from 2020 Peanut Production - April 9, 2021

- Sprayer Calibration Tables – Calibration Made Easy - October 30, 2020

- Stand Issues – Should You Replant Your Peanut Field? - May 15, 2020