A photo of the Spring 2020 watermelon foliar diseases management trial at the UF-IFAS-NFREC in Live Oak. Credit: Susannah Da Silva, UF/IFAS

Susannah Da Silva, Mathews Paret, Bob Hochmuth, Fanny Iriarte, Ben Broughton,UF/IFAS North Floirida Research and Education Center, Pam Roberts, UF/IFAS Southwest Florida Research and Education Center, and Bill Turechek, USDA ARS

Approximately 6500 acres of watermelons are produced in North Florida annually. The plants are transplanted from late February to late March and harvested during the major market window, which is roughly from Memorial Day through July 4th. The production cycle starts with seed companies in the U.S and internationally, producing high quality seeds in field production around the world. A series of good practices including sanitation of equipment, scouting for diseases and insects, clean soil and water, exclusion of specific pathogens, use of fungicide and insecticide spray programs, routine diagnostic testing and seed treatments to minimize the risk plant pathogens in the seed are practiced.

These steps are followed by producers procuring the seed, as well as transplant producers growing plants in greenhouses with overhead irrigation systems, under high humidity conditions in Florida, Georgia and other states in the U.S. In addition to these practices, transplant producers include sanitation of seedling trays and routine aeration of the greenhouses to manage humidity, thus minimizing survival and spread of plant pathogens. The rigorous quality standards followed in seed and transplant production are critical to reduce the risks of plant pathogens in commercial watermelon production.

While clean seed and transplant production is the critical first step, management of diseases during field production in North Florida can be extremely challenging for watermelon producers. In the recent years there has been a significant impact from gummy stem blight, downy mildew, and powdery mildew; three highly destructive diseases of watermelon. The biology of the pathogens causing these diseases, and the wide range of conducive environmental conditions in which they could survive and spread, plays a huge role in this. In addition, lack of disease resistant commercial watermelon varieties and development of pathogen resistance to many groups of fungicides limit management options.

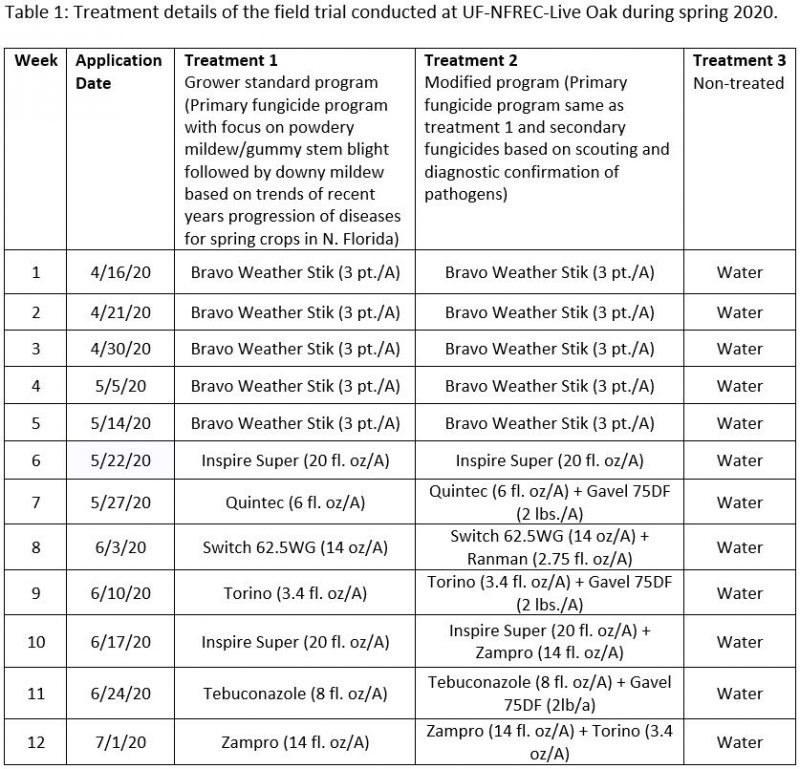

The 2020 Florida Watermelon Fungicide Spray Program outlines options for management of these diseases including a fungicide program tailored for different foliar pathogens. For example, in that document a primary program for foliar fungal diseases can be found similar to Treatment 1 listed in Table 1 below. While symptoms of gummy stem blight, downy mildew and powdery mildew are distinct, they can be confused during early stages of lesion development and when multiple lesions merge together, which is common. Thus, diagnostic confirmation in a lab is critical in making the appropriate secondary fungicide choices, in addition to the primary fungicide program targeting specific diseases.

–

A field trial conducted at UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center-Live Oak during the spring of 2020 compared the grower standard spray program (Treatment 1) with a modified program that used scouting and diagnostic confirmation to add a secondary fungicide to the grower standard spray program (Treatment 2), with both treatments compared to the water only control (Treatment 3) from Table 1 above.

–

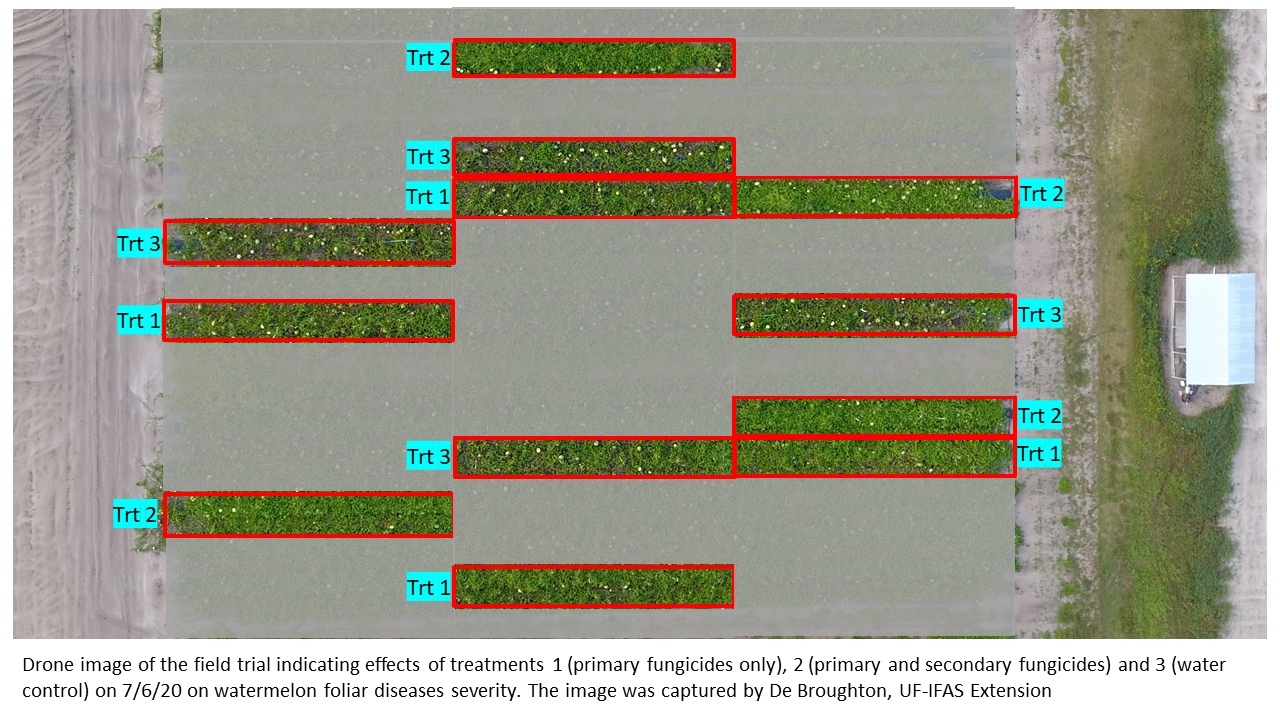

The study showed that the standard grower spray program (Treatment 1) focused on powdery mildew/gummy stem blight as key target diseases that did not take field scouting and diagnostics into perspective had very high disease severity compared to a modified program (Treatment 2) that used the primary fungicides in Treatment 1 and secondary fungicides based on early diagnostic confirmation of downy mildew in late May. The secondary fungicides used for management of downy mildew were Gavel 75 DF, Ranman and Zampro.

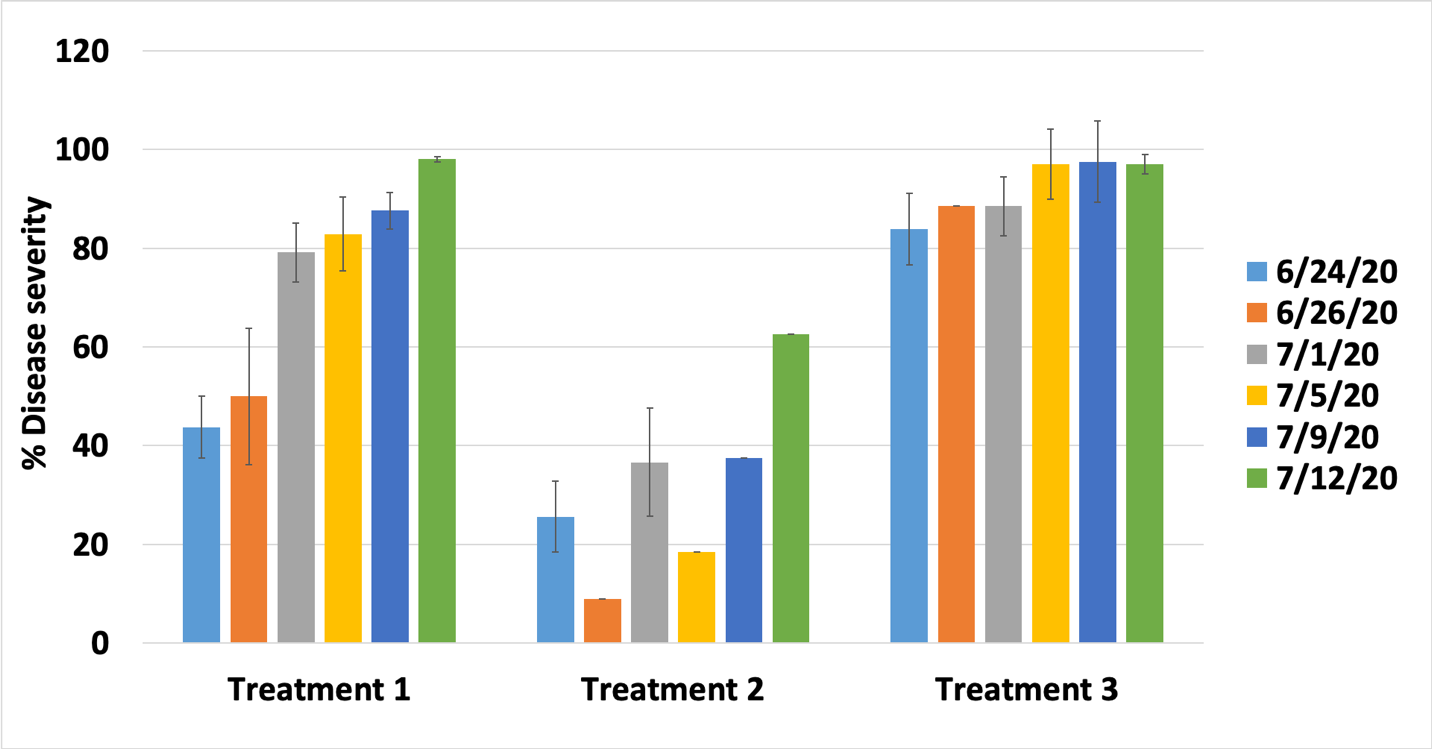

Looking at data from the final weeks in the study (Figure 1 below), on 7/5/20 (yellow bar), four days after the final application day, Treatment 2 had an average disease severity of 19% compared to 83% for Treatment 1 and 97% for water control. Subsequent assessments on 7/9/20 (blue bars) and 7/12/20 (green bars) also indicate the positive impact Treatment 2 had on long-term protection of plants from foliar diseases.

Fig. 1. Progression of disease severity (%) of all foliar diseases (downy mildew, gummy stem blight, and powdery mildew) under two different spray programs and water control, from 6-24-20 to 7-1-20, and beyond the final application date from 7/5/20 to 7/12/20. The error bars represent standard error of mean.

–

The authors would like to note that if the primary program selected for this experiment was for downy mildew instead of powdery mildew/gummy stem blight, the outcome could have been different for the grower standard program. This is based on the fact that this trial had early downy mildew incidence and more downy mildew severity than gummy stem blight and powdery mildew. Irrespective, the study demonstrates how field scouting and diagnostics play a significant role in improving a watermelon grower standard program with timely use of secondary fungicides in addition to primary fungicides. This study is being replicated at UF/IFAS SWFREC, in Immokalee, and USDA-ARS, in Fort Pierce.

–

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge USDA-AMS-FDACS Specialty Crops Block Grant Program Award 026708 for funding this project, and the Florida Watermelon Association for support of this research. We also like to acknowledge De Broughton for collecting the drone imagery, and the farm crew at UF-NFREC-Live Oak and the fungicide companies who donated chemicals for this study. The principal investigators of this project were Dr. Pam Roberts, Dr. Bill Turechek, Dr. Mathews Paret, and Bob Hochmuth.

- Mathews Paret Promoted to University of Florida Plant Pathology Department Chair - July 28, 2023

- Field Performance of Plant Protectants against Bacterial Leaf Spot on Watermelon - February 11, 2022

- Using Scouting and Diagnostic Confirmation to Improve Watermelon Spray Programs in North Florida - September 25, 2020