Saundra TenBroeck, UF/IFAS State Extension Horse Specialist

Summertime brings many positives for horse owners: longer days, shorter hair coats, and lower feed bills, utilizing pasture instead of hay. Some of the challenges that arrive with hot/humid days of summer include keeping your horse cool and hydrated, replacing electrolytes, preventing sunburn, increased disease challenges from biting insects, pasture weeds, and potential allergies.

–

Sweat evaporation is the horse’s primary means of dissipating heat, but with high humidity, it is difficult for horses to cool down because evaporation is hampered. UF/IFAS Archive

–

Keeping cool

Thermoregulation is the maintenance of body temperature within a narrow range. When horses exercise, the cellular process that releases the energy needed for muscle contractions produces heat as a by-product. Heat must be removed, or muscle function is hampered (fatigue). Evaporation of sweat is the horse’s primary means of dissipating heat, but with high humidity, it is difficult for horses to cool down because evaporation of sweat is hampered.

Recommendations:

- Take it easy during summer months

- Ride in the early morning or evening

- Cool down at the end of your ride

- Hose your horse with cool water after the ride (neck, chest, between legs)

- Turn horses out during the cooler time of day.

- Make sure horses have access to shade.

- Provide fans to increase air flow.

- Transport during the cooler part of the day.

–

–

Hydration

Fluid Loss from Sweat increases as temperature and humidity increase. In cool to moderate conditions a horse will lose 6-8 liters of fluid per hour but in hot and humid conditions, a horse can lose up to 15 liters of fluid per hour. Fluid loss increases as exercise duration increases. Example: A thoroughbred doing a warm-up and ~2-minute race can lose 6 liters of fluid, while a 50 mile endurance race will elicit a loss of 50 liters of fluid.

–

Electrolytes

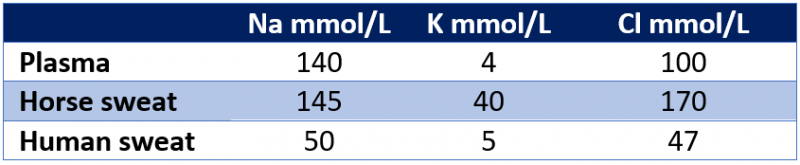

In addition to fluid, horses also lose electrolytes (Na, K, Cl) in sweat. Have you ever heard the saying, “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink?” There is a physiological explanation for that. Sweat comes from plasma (blood). In horses, similar amounts of water and electrolytes are lost in sweat, so the concentration of electrolytes in the plasma of the horse remains relatively unchanged after exercise. Contrast that with humans in which more water is lost in sweat than electrolytes, so the plasma concentration of electrolytes increases. The trigger for thirst is elevated plasma Na. Since the Na concentration in plasma does not change, the horse doesn’t feel thirst in the same way a human athlete would.

Recommendations for keeping your horse hydrated:

- Provide free access to clean, cool water at all times.

- Check hydration by tenting the skin on the neck or checking the gums for capillary refill time.

- Replace electrolytes lost in sweat by providing free choice salt and/or electrolyte supplements.

- NOTE: Some horses are classified as anhidrotic which means they do not sweat properly. This can be life threatening if not monitored and managed.

–

Sunburn

Prevent sunburn by applying sunscreen to areas of pink skin (typically the nose). Fly masks and fly sheets also provide protection from the sun. For stalled horses, keep them up during the day and turn out from evening to dawn during the summer months.

–

Noxious weeds

Though warm, wet weather allows our pasture grasses to rebound, weeds are a consistent challenge to pasture productivity and horse health. Though most toxic weeds are not appetizing to horses, if adequate forage is not available, horses may consume things they normally wouldn’t. Learn to identify noxious weeds and remove them from your pastures. Frequent mowing, rotational grazing, strategic application of herbicide, and managing soil fertility and pH are all important parts of pasture management.

–

Aedes albopictus, the most common day-biting mosquito in much of Florida. Photo by Le Munstermann of Yale University.

Disease challenge

Insects vector many diseases, cause economic losses and are generally a nuisance. Each summer rainfall event is typically followed by a large hatch of mosquitos. Mosquitos vector most blood borne diseases including EEE and West Nile. Your vaccination program should consider mosquito prevalence as well as potential travel. Disease prevention is best accomplished by increasing disease resistance (vaccinate) before the disease challenge is present.

–

Allergies

Some horses are allergic to bug bites. Fly sheets/ masks, insect repellents, pesticides, fans and selective turn out times can mitigate fly challenges.

Pasture heaves have been identified in many Florida horses grazing Bahia pastures infested with an endophyte fungus. Late summer and early fall these horses develop lung inflammation resulting in elevated respiration rate, coughing and intolerance to exercise. Removing the horse from pasture and providing preserved, dust free forage is the best way to manage a horse with this problem.

–

Take Home Message

Summertime brings opportunities and challenges. Work and/or haul your horses in the cooler part of the day. Vaccinate prior to travel and mosquito season. Keep clean, fresh water and minerals available at all times. Use fans, fly repellents, fly masks, and sheets as needed. Identify problems and adjust management to mitigate risk.

–

References:

The Scoop on Horse Sweat: Learn what’s normal, what’s not and how to keep your horse hydrated and healthy when the weather turns hot. Elaine Pascoe with Duncan Peters, DVM, MS, for Practical Horseman magazine

Horse Health After an Immune Challenge. Stacey Oke, DVM, MSc for the Horse

Managing Summer Pasture-Associated Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, an Asthma-like Disease of Horses. Lais R. R. Costa; Jill R. Johnson; Cyprianna H. Swiderski; Department of Clinical Sciences at Mississippi State University and Equine Health Studies Program at Louisiana State University

- Dr. Saundra TenBroeck is Looking Forward to Looking Back after 40 Years of Service - October 10, 2025

- End of Life Issues – Euthanasia:A Horse Owner’s Final Act of Care - October 4, 2024

- Economic Impact Study Indicates the Florida Equine Industry Remains Strong - April 12, 2024