Marcelo Wallau, Forage Extension Specialist UF/IFAS

This past week I was invited by a colleague from Costa Rica, Dr. Luis Villalobos, to provide a virtual presentation on pasture management for an audience of students, producers, and consultants from multiple places around Central and South America. We had a very interesting conversation, and I would like to share it here as a resource for our Spanish-speaking population. The video is available at the “Escuela de Zootecnia” from the “Universidad de Costa Rica” Facebook page.

Grazing management is always a very “intensive” topic to be discussed (no pun intended), especially with new management gurus popping up here and there. I always get asked “What is the best grazing system?”, or “Should I move my cattle three times a day or every three days?” etc. What matters most is that forage growth (i.e. pasture production) and grazing behavior (pasture harvest) principles are followed. Then you can adjust your grazing management as you see fit. But, it is important to understand those core ideas to get the most out of it. And, indeed it is possible to obtain an “optimal” (a word I don’t frequently like using) level of pasture and animal productivity.

–

Stocking Rate

Recycling an article entitled, “What is the right grazing management?” that Dr. Jean Savian (INIA Uruguay) and I wrote for Progressive Forage last year, we first need to think about how much forage we can produce and how much forage is needed. If that balance is negative, i.e. we need more forage than we can produce, there is no grazing management that will fix it. You will need to buy feed or remove cattle. This leads us to the concepts of carrying capacity and stocking rate, well explained by my colleague Dr. Matt Poore, NC State, in his article entitled, “Managing Your Stocking Rate.” There are, indeed, management tricks that can help to increase the carrying capacity of your existing pasture, but you can hardly focus on rotating cattle more frequently, etc. without first addressing some other issues such as weed encroachment, soil fertility, and seasonal overstocking that I shared in the article published recently, “Effective Management of Warm-Season Pastures During the Spring Transition.” But let’s talk about grazing management, which is the topic of the talk aforementioned. I like to think about pasture management from the animal behavior perspective; How can we present the animal with a pasture structure that allows for grazing without limitations? By without limitations, I mean that every time the animals lowers their head to take a bite, it is able to get a full bite that will enable it to harvest all or most nutrients required in the least amount of time.

Imagine two scenarios: a recently planted growing pasture, or a pasture which you are returning to graze after a resting period. On a growing pasture, in the beginning, we have tender, high-nutritive value forage. However, the amount of biomass is very limiting. This reduces the size of the bite and the animal cannot harvest the necessary amount of forage in a day (Figure 1, left). Very good quality but not enough quantity. As the pasture grows, we reach the midpoint where we have the best compromise between quantity and quality. The canopy is dense, allowing for full big bites of fresh forage, and the animals can eat sufficient forage in less time (Figure 1, right). In other words, the animal harvests only the best (leaves). As we move forward, and the pasture becomes more mature, we see more stems, then dead leaves and seedheads appear. At this point, the quality drops, and the animal starts sorting more, which means more time grazing to achieve the required daily intake and more forage “wasted” by sorting and trampling.

Figure 1. Heifer grazing a very short canopy (left) limiting bite mass and resulting in extended grazing time to harvest necessary nutrients; and (right) cows grazing am intermediate (i.e. not overly mature) bahiagrass canopy, being able to take a deep bite, and harvest more forage and faster. Credit: Marcelo Wallau, UF/IFAS

–

Rotational Grazing

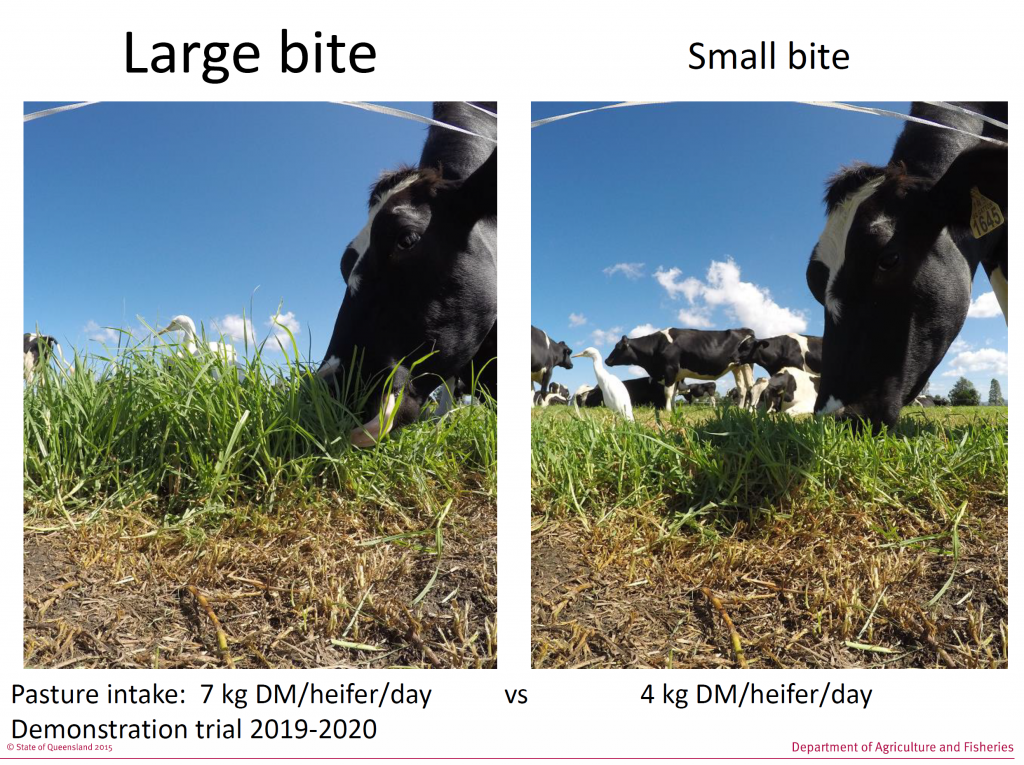

In a second scenario, considering a pasture that has been well managed, and we are back to graze it at the top of that exponential growth phase. Now, let’s divide this pasture canopy in three layers: top, middle and bottom. The top part of the canopy has the most leaves, and the animals will move along the pasture harvesting mostly that top layer. As animals move into the second layer, which is composed of a mixture of stems and leaves, quality declines some, but there is still a good amount of biomass allowing for big bites. Then animals move to the bottom layer, which is composed basically of stems and dead leaves, with lower density of forage (sparser). This effect is exacerbated when we have very long regrowth intervals on actively growing pastures, where the canopy is overly mature, full of seedheads and dead material. At this point, the animal not only has low-quality material to eat, but struggles to harvest that forage, and this has a large impact on performance. Borrowing a slide from a colleague, Dr. Marcelo Benvenutti, Queensland, Australia, we can see in the photos below (Figure 2) that as we leave the animals on a pasture to graze that second layer, to get “just a little bit more”, we are limiting intake tremendously! As a rule of thumb, as you look at the pasture and you see that most of that top layer has been grazed, the animals are already about halfway through the second layer. It is time to rotate to fresh pasture!

Figure 2. Heifer grazing the “first layer” of a Kikuyu canopy (left), resulting in a dry matter intake of about 15.5 lbs per day, and recurrent grazing on the same pasture (second layer) which reduces intake to about 9 lbs of dry matter per day. Credit: Marcelo Benvenutti, State of Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

–

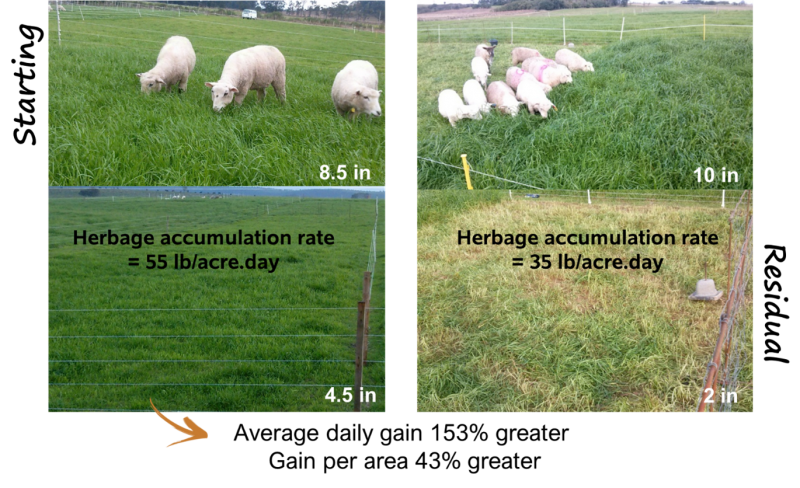

So, how does that translate into pasture productivity and animal performance? Figure 3 below presents two grazing management approaches, a more frequent and lenient (fast rotation and 40% of initial biomass removed) vs. a “traditional” rotational system, where we target harvesting efficiency (80% removal). After grazing, the large amount of residual leaf area on the lenient management (left) permits a fast regrowth (higher daily herbage accumulation rate), which, at the end of the season, also results in more total biomass produced. Furthermore, since animals are only “eating the best”, performance is higher and compensates for the lower stocking rate. In this example, it was possible to get almost 60% more forage production, 153% greater individual animal performance and 43% greater animal gain per area using a lenient grazing approach. There is a lot more to discuss here, but we will leave it for another opportunity. Stay tuned in to the UF Forage Team Facebook and Instagram accounts for updates and materials. For more information, contact your local extension agent, or email me at forages@ifas.ufl.edu.

Figure 3. Sheep grazing Italian ryegrass on rotational systems, a lenient and more frequent approach (40% removal; left) and a traditional rotation with longer regrowth interval and 80% biomass removal (right). Source: Jean Savian, INIA Uruguay.

- UF/IFAS 2025 Top Rancher Challenge Showcases Youth and Adult Talent - July 11, 2025

- Cow Talks: Special Guests Discuss the Impact of H5N1 Avian Influenza on Agriculture - April 25, 2025

- Why is this weed here? Weed Management in Pasture Systems - February 28, 2025