Marcelo Wallau, Forage Extension Specialist, Agronomy Department, Nicolas Caram, PhD student, Agronomy Department, and Brent Sellers, Weed Specialist, Range Cattle Research and Education Center

With warm temperatures and recent rains, bahiagrass and bermudagrass pastures have broken dormancy and started greening up (Figures 1 and video). Folks get excited and many see this as a sign of relief, “No more feeding hay!”. Well… we might not be quite there yet, and pasture management decisions will have season-long impact. Especially grazing management, fertilization, and weed control.

Figure 1. Side by side, spring green up of Pensacola bahiagrass pastures, with rhizoma perennial peanut (left) and without (right), in Gainesville, FL, on March 8th, 2023. Neither pasture has received nitrogen over the past 3 years.

–

–

What is happening

This early bahiagrass and bermudagrass growth is, in fact, quite slow. Plants are using their reserves that were accumulated last fall to kickstart the season, slowly putting up new tissue (new leaves) that will then produce energy. Days are still short, nights are somewhat cold (low temperatures are forecasted for next week), and growth is slow. As a matter of reference, the bahiagrass growth that is happening now is likely in the range of 5 to 10 lbs of dry matter (DM) per acre per day, whereas in the summer, depending on fertilization, growth would be anywhere between 40 and up to 60 lbs DM per acre per day (Figure 1). Put in perspective, an 1100-lb cow would be grazing somewhere between 22 and 27 lbs of DM per day. If we consider harvesting half of that growth (yes, just half, we need to leave adequate leaf area behind to keep the grass growing – otherwise we are overgrazing), that means we need between 5 and 10 acres to feed that cow without compromising the pasture. Beyond that, the amount of forage the cow will be able to harvest per bite is quite small, meaning that it will spend more energy grazing to consume adequate fill. Alternatively, in the peak of the summer, we will need basically 1 acre per cow. So, how can we manage this?

–

Managing the Spring Transition

It is very important to understand forage seasonality, because how we manage it will influence season-long productivity. Many producers are feeding hay on top of those same bahiagrass pastures that are greening up. That fresh growth is like candy for cows that have spent the winter eating “cow hay”. They will graze every blade of it if we don’t take precautions. As cows remove that early growth, plants need to dig deeper into their reserves for extra growth. This slows down the growth rate, reduces total seasonal production, depletes plant reserves, and opens more space for weeds.

So, what can be done? The main thing is to keep cows off the fresh growth until there is sufficient biomass to be grazed (about 1400 lbs of DM per acre, or at least 6-8 inches of forage). This probably means we will be feeding hay a little longer. Although it adds expense, it will ensure the productivity and persistence of the pasture. This can be accomplished simply, by fencing off (temporary fence should be sufficient) a feeding area or restrict access to one sacrifice pasture, while giving a chance for the remaining areas to grow.

The situation is similar with bermudagrass. In general, bermudagrass tends to come on slower in the spring compared to bahiagrass, but that may not be the case with some new varieties. Both Mislevy and Newell, recently released by UF researchers, are already showing quite a bit more growth than Tifton 85 (Figure 2).

–

Other Management Decisions

Now is the time to create a plan for weed control and fertilization. Both, however, are weather dependent. The NOAA seasonal precipitation outlook (Figure 3) shows good chances of below-average rainfall for the period Mar-Apr-May. Late spring is normally dry, which means this year is likely to be dryer than normal. While early-season weed control is often recommended, it is important to take current weather conditions and forage growth into consideration. In general, the response of weeds to herbicides is optimum under good growing conditions, and drought stress can negatively impact herbicide activity. If weeds are wilting at any point during the day, it is best to delay herbicide applications until weeds resume active growth following rainfall. There are also some situations where forages can also be more susceptible to unintended herbicide damage or delayed green-up during the spring transition. In terms of pasture herbicides, early is good, but don’t get too far ahead of yourself. Most pasture products primarily have postemergence activity on weeds – make sure the weeds are leafed out and ready to spray before you make an application. This slight delay will generally get you through the forage transition as well.

Figure 3. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAAA) seasonal precipitation outlook for Mar-Apr-May 2023. Source: Climate Prediction Center

–

Spraying when weeds are small provides more efficient and economical control and reduces competition thereby enhancing forage growth. Before deciding on what herbicides to use, find out what weeds are present and what are the most problematic (e.g., which ones are the main target). While there are likely winter annual weeds present in pastures right now, it’s probably a little late to build a herbicide program around them. They are soon to die off with hot weather and will likely have very little impact on summer pasture productivity. On the other hand, it is time to start gearing up to control real pasture performance robbing weeds like tropical soda apple and hit some summer annual weeds (that have already flushed with the uncharacteristic warm weather) before they have a chance to compete with your pasture. If you have questions about specific weed species and recommended herbicides, check out “Weed Management in Pasture and Rangeland” or contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agent.

In terms of fertilization, spring is generally a good time for a first application of a complete fertilizer – nitrogen (N) plus recommended phosphorous (P) and potassium (K) from the soil analysis. Early fertilization can get pastures growing faster, which provides for an earlier grazing season and ensure a good stand of plants for the growing season. The only concern is what type of weather we will have ahead of us. Before deciding on fertilization application, keep an eye on the 2-week forecast, and make sure there is rain coming. If we don’t get a good rain until mid-April (for North and Central Florida), chances are that we will need to wait until late May or June for more regular rains to receive the full benefit of the nitrogen application. If uncertain, perhaps fertilizing part of the pasture might mitigate the risks.

As an example of the early fertilization effect, note the difference in growth of the two Pensacola Bahiagrass pastures in Figure 1 above. The right panel is bahiagrass monoculture, without fertilizer; the left panel is a 35+-year-old stand of bahiagrass and rhizoma perennial peanut. The legume adds nitrogen to the system via biological N fixation, which is recycled via plant and root turnover, root exudates, and animal excreta (during grazing). There seems to be much more growth already on the pasture with the legume compared to the grass monoculture. Moreover, the legume introduction could determine greater growth and animal performance, with lower economic and environmental costs compared to a bahiagrass monoculture fertilized with N.

The UF/IFAS recommendations suggest three approaches for nitrogen fertilization for bahiagrass pastures for grazing:

- Low – 50-60 lbs N/A in spring.

- Medium – 100 lbs N/A in split applications, spring, and summer.

- High – 160 lbs N/A in split applications, spring, and summer.

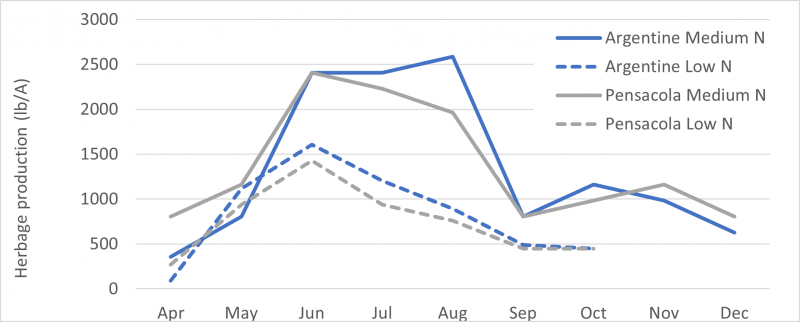

Most farmers opt for the low input system or even no fertilization. But the “cheap” strategy can end up costing more on weed control, supplemental feeding, and lower animal performance. Proper fertilization can increase bahiagrass production 2 to 4 times. Figure 4 (adapted from Mislevy et al., 2003 and Vendramini et al.,2015) illustrates the difference between the “low” and the “medium” input approach. Note that after the early peak of production, the “low” fertilization drops down, while we continue to have high production throughout the summer when adding that second application of the N fertilization.

Figure 4. Herbage production for Argentine (blue lines) and Pensacola (gray lines) bahiagrass under medium (100 lb N/A; solid lines; Mislevy et al., 2003) and low (53 lb N/A; dashed lines; Vendramini et al., 2013) nitrogen fertilization in Ona, FL. (From Ask IFAS – Bahiagrass: overview and pasture management ).

–

Beyond N, make sure P and K levels are sufficient and fertilize according to soil analysis. Fertilization should be based on a soil test. Bahiagrass pasture decline is often seen when those nutrients are neglected. The good news is that fertilizer prices are going down. We are not yet at the same price level as 2 years ago, but we are down $200 (25%) per ton at local retailers compared to this time last year. It might be time to reconsider picking up your fertilization program.

Last, keep in mind that good fertility management and weed control cannot offset poor grazing management. This is particularly true in cases of over stocking/over grazing. So, the first step, which has no costs, is adjusting the stocking rate to avoid overgrazing and planning the overall forage and feeding management to take the most advantage of this early onset of the growing season. Only after grazing management is addressed will it be possible for increased fertility and weed management to generate an economic return.

If you have any questions or would like to brainstorm some strategies on how to plan your fertilization and weed control, reach out to us at forages@ifas.ufl.edu and consult with your local extension agent.

- Cow Talks: Special Guests Discuss the Impact of H5N1 Avian Influenza on Agriculture - April 25, 2025

- Why is this weed here? Weed Management in Pasture Systems - February 28, 2025

- What to Look for When Selecting Hybrid Corn Varieties for Silage? - January 31, 2025