Dealing with pinkeye in cattle is a common and frustrating battle for the cattle industry. While the main issue may seem to be impairment of vision, major financial impact is found in an overall decline in cattle performance. A 1993 study estimated pinkeye costs U.S. cattle producers $150 million annually. This is a result of decreased milk production, weight gain, and the cost of treatment.

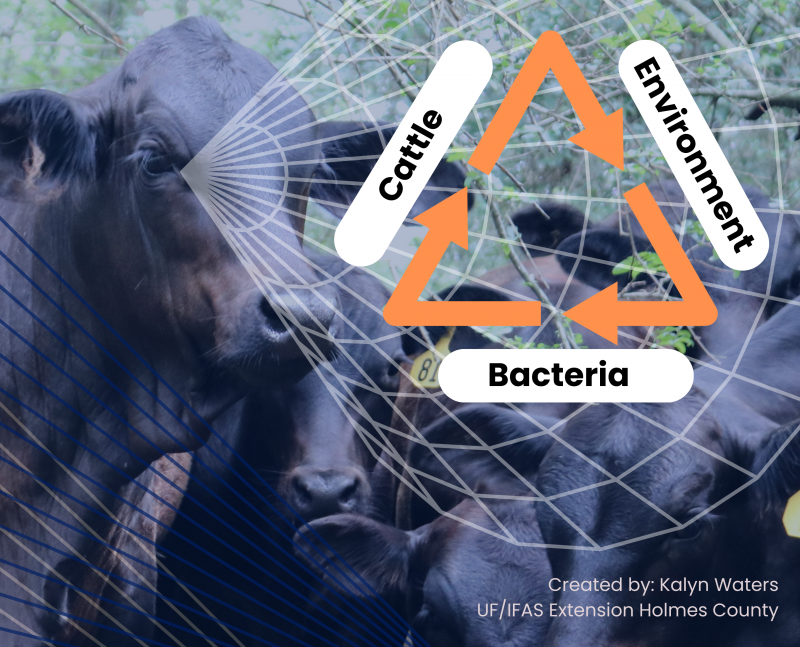

You can think of pinkeye as a three-part issue: 1) the bacteria, 2) the cattle, and 3) environmental triggers.

–

1) THE BACTERIA

Moraxella bovis (M. bovis) is the primary infectious agent that causes pinkeye in cattle. Cattle carry the bacteria in their nasal cavities and the inner surface of their eyelids and it can be present in cattle with no clinical signs. Typically, these cattle have already been exposed and recovered. In happy and healthy circumstances, the bovine eye can compensate and overcome M. bovis. For the bacteria to result in infections generally there is an underlying assault or injury to the cornea. Inoculation time is typically 2-3 days, with the peak of the outbreak occurring in the third or fourth week.

–

2) THE CATTLE

Age, immune strength, and stress all play into cattle’s ability to overcome pinkeye. Younger cattle are typically at a heightened risk. Over time cattle develop an acquired immunity with protective antibodies on the eye surface. In addition, cattle that are genetically inferior, on a suppressed plane of nutrition, or are stressed are at a higher risk of contracting pinkeye.

–

3) ENVIROMENTAL TRIGGERS

The first two factors (bacteria and the cattle) can be out of our control in most situations. Where we have more control as producers is managing the environmental triggers for pinkeye. There is a laundry list of environmental factors that can result in irritation or injury to the cornea that will allow for pinkeye to take hold in a herd. These include sunlight, grass/weed seeds, hay, flies and basically anything else that can cause injury or irritation to the eye.

When producers take all three factors into considerations, the best way to tackle pinkeye management in the middle of a summer outbreak might be mechanical. Taking steps to control environmental triggers can be a solid management strategy when paired with strong genetics, nutrition and potentially a vaccine. Mechanical control would include plenty of shade to limit UV insult and keep cattle from tightly bunching during hot parts of the day. Additionally, keeping weeds and tall grasses mowed to limit physical eye irritation that allows for M. bovis to incubate. Other steps that may add to control would be limiting dust in working pens by watering before penning cattle and working, and to provide effective fly control.

By working to limit environmental factors that make cattle susceptible to pinkeye infection, producers can help limit the financial impacts of pinkeye. Working closely with a veterinarian is also key in the battle against this seemingly simple yet costly infection.

- Horn Fly Control In Cattle - June 20, 2025

- Tips for Introducing New Chickens into Your Coop - April 25, 2025

- Tips for a Great Chicken Coop - April 11, 2025