Whether we are watching a NCBA Cattlemen to Cattlemen episode covering a successful commercial operation or reading about a well-established, multigenerational seedstock operation, one management practice seems to be a common thread for success…”culling”

Removing females from your herd that are not performing in their environment while receiving adequate management support is critical to being a profitable cattle producer. Females can be culled from a herd for numerous reasons spanning from production issues such as failure to become pregnant, phenotypic issues such as bad udders, or soundness issues.

Think of it this way: Cow A breeds this year, Cow B does not. Why would you keep Cow B? It’s easy to justify Cow B’s lack of performance. She was young, it was a hard winter, or she weaned a heavy calf. However, Cow A was subject to the exact same management and performed, yet Cow B did not. Cull Cow B and get another Cow A!

In addition, financially, in a commercial setting, it is nearly impossible for Cow B to ever overcome the loss of production value from that year. In 2016, the average annual operating cost per cow was $700. If retaining a 5 year old cow that is expected to wean 5 more calves in her lifetime (weaning 500 pound calf at $1.40), she would need to wean an additional 100 each year to pay for her “open” year, and in the words of Silas “Si” Robinson “That ain’t happening, Jack”!

In many cases, young cows are retained if they are open, with the justification that “we have too much in her to get rid of her at this point.” This is in reference to the cost of replacement heifer development; however, salvage value on a young cow is much higher than an older cow. In addition, as mentioned above she would need to wean an extra 71 pounds a year for the next 7 years to pay for her “open” year, and will likely continue to under perform in her environment.

With the added value of a purebred/seedstock calf, producers are more likely to be able to overcome the cost associated with retaining an open cow. But then we must ask ourselves, “Should seedstock producers be keeping open cows?” Ideally, cows who are sub-fertile would be culled from a herd, regardless of their ability to recoup the cost of their missed calf. While the short term math is simple, allowing subfertility to exist within a herd, long term, will be extremely expensive. More concerning, a seedstock producers who is willing to allow sub-fertile cows to continue to contribute to their genetic foundation, likely is not producing highly fertile/profitable genetics that should be introduced into your herd. Thus, it’s important to know the culling strategies of your seedstock producer as it is key in making sound genetic decisions.

–

Genetic Progress

Genetic Progress

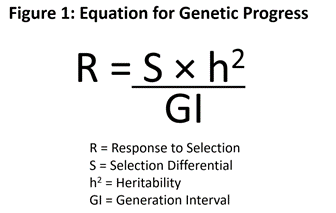

Having an understanding of how genetic progress is calculated helps drive home the importance of culling sub-performing cows from our herd. Genetic progress (figure 1) is a function of selection pressure, heritability and generation interval. Each component plays a different role in the genetic progress of your herd. However, progress cannot be made, nor production be maintained if one component is missing.

–

Section Differential

Defined as the variance in the average genetics of an animal selected for breeding and the average genetics of the remaining animals in the herd. The tighter the selection pressure, the great genetic standard that is maintained. For example: selecting 20 replacement heifers from 100 vs. selecting 45 replacement heifers. When you select a smaller proportion of the population, you are able to make more critical selection decisions, keeping better heifers.

–

Heritability

Heritability

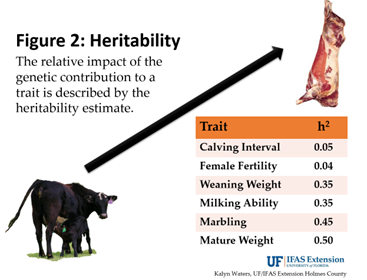

Heritability is the proportion of measured difference between animals that can be attributed to genetic differences between animals and will be passed on to progeny. The higher the heritability of a trait, the greater the proportion that this trait will be passed on to the offspring from both parents, and therefore, the greater the genetic progress that will be achieved. In general, the closer to the end point (carcass) a trait is the more heritable it is, whereas traits that are expressed at the beginning of the production chain, such as maternal traits, are less heritable (Figure 2). Keep in mind that maternal traits are strongly influenced by moderate to highly heritable traits that is why culling influences fertility and certain cow families tend to thrive under certain management conditions, while others struggle.

–

Generation Interval

As the lone denominator in the equation for genetic progress, generation interval has the greatest impact on genetic progress. Defined as the average age of the parents of a herd at the time of offspring birth, a short generation length means that animals selected for breeding are mated in the herd at a younger average age. Reducing the generation length will generally increase the rate of genetic progress. However, when making mating decisions, we know that younger animals have lower accuracy in their EPDs.

Research from the University of Missouri in 2012 shows that slight changes in management can result in major increases in production and that focusing on decreasing generation interval, while increasing selection interval is the greatest way to move the genetics of your herd forward.

- Increasing accuracy by 20% = 16.7% increase in genetic progress

- Increasing selection intensity by 20% = 20% increase in genetic progress

- Decreasing generation interval from 5 to 4 years of age (20%) = 25% increase in genetic

In summary, culling sub-fertile or unproductive females from your herd is one of the most important management tools for cow/calf producers. In addition, if a cow does not produce a calf every year, she will never be a profitable female in your herd again. Through an understanding of genetic progress and management practices, producers can use culling to maximize the efficiency of their herd.

–

*Adopted from article originally published by Progressive Cattlemen and written by Kalyn Waters

- Horn Fly Control In Cattle - June 20, 2025

- Tips for Introducing New Chickens into Your Coop - April 25, 2025

- Tips for a Great Chicken Coop - April 11, 2025