Saundra Tenbroeck, State Extension Horse Specialist, UF/IFAS Animal Science Department

Geriatric horse that was euthanized to stop the suffering from chronic diarrhea and significant weight loss. Credit: Saundra TenBroeck, UF/IFAS

One of the more difficult topics to address, relative to horse ownership/management, is end of life issues. Harvest of horses for human consumption is not currently practiced in the United States, so death by natural causes or euthanasia are the options for sick, injured or elderly horses. Horse owners must plan for the inevitable.

–

Is it always best to wait for a horse to die of natural causes?

Euthanasia, derived from a Greek word meaning “good death,” is the ending of life in a way that minimizes distress and pain. Euthanasia as an end to suffering is strongly associated with animal welfare, making the actual moment of death as peaceful and painless for the animal as possible (Arluke and Sanders, 1996). Since horses are property, owners have the legal right as well as the responsibility to make the decision on the timing and method of death (Cudworth, 2015). Circumstances that might warrant euthanasia include extreme pain; incurable, progressive disease; incurable, transmissible disease (EIA); inoperable colic; chronic lameness (founder). Some of the circumstances that may require an owner to make the decision to euthanize include foals with congenital or genetic defects; severe traumatic injury (long bone fractures); dangerous behavior; undue financial burden of caring for a sick or incapacitated horse; debilitation in old age (dental wear).

–

Considerations

–

-

What is the likelihood of recovery?

– -

What are the chances of the horse returning to service?

–

-

Is the horse suffering? (Appetite is the primary consideration as well as weight loss)

–

-

How much can the owner handle during recovery? (Long term vs. short term care)

–

-

What is the owner’s ability to commitment the time needed for care and/or do they have adequate facilities to allow recovery?

–

-

What are the alternatives?

–

-

How does the horse respond to pain, respond to treatment, his will to survive?

–

If you have a mortality insurance policy, read it carefully, inform the company; may need a second opinion. Determine is the horse meets the criteria for coverage. Is the condition chronic or incurable? Does the immediate condition suggest hopeless prognosis? Will the horse require continuous pain medication for the rest of its life? Is the horse dangerous to himself or others?

–

If euthanasia is chosen, what are the options?

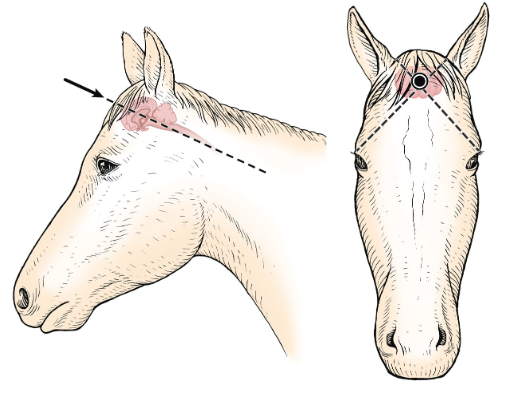

Horses may be euthanized by gunshot or penetrating captive bolt. Not between the eyes, but on the intersection of 2 lines each drawn from the outer corner of the eye to the top of the opposite ear. Credit: Procedures for Humane Euthanasia, Iowa State Extension

The technique chosen must cause immediate loss of consciousness followed by cardiac and respiratory arrest, ultimately resulting in loss of brain function. The AVMA considers three methods “humane”.

Overdose of intravenous barbiturates is the most common method for equine euthanasia by veterinarians (AVMA). Unfortunately, animal remains contain potentially toxic barbiturate residue that threatens wildlife, domestic animals as well as a contaminate to soil and water. Disposal of remains must be conducted in accordance with federal, state and local regulations. Use of these drugs invoke legal responsibilities for veterinarians and owners to properly dispose of carcasses. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act may carry civil and criminal penalties, with fines in civil cases up to $25,000, in criminal cases up to $500,000, and incarceration for up to 2 years

Penetrating captive bolt and gunshot are less commonly used but highly effective and acceptable methods. These methods should only be used by people who are well trained. Done correctly, this method causes massive brain destruction and immediate death with a carcass that is safe for any method of disposal. Few veterinarians are trained in these two methods.

–

When the life force is gone, a carcass remains. What are the acceptable outlets for disposal and is cost recovery an option?

Some ranchers have adequate land and may let nature take over. The carcass will be consumed by buzzards, coyotes and other carnivores as well as fire ants. Barbiturate residues can be fatal to wildlife so this would only be an option if the if firearm method is used.

-

Commercial rendering is available in some places, but availability is declining for chemically euthanized horses.

–

-

Incineration may be an option but is often cost prohibitive.

–

-

Burial is an option but environmental regulations in your state/county may prohibit it due to concerns over ground water contamination.

–

-

In some locations, there are people who will collect animals that have died or that are euthanized by gunshot and sell the meat to Zoos or wild carnivore reserves.

–

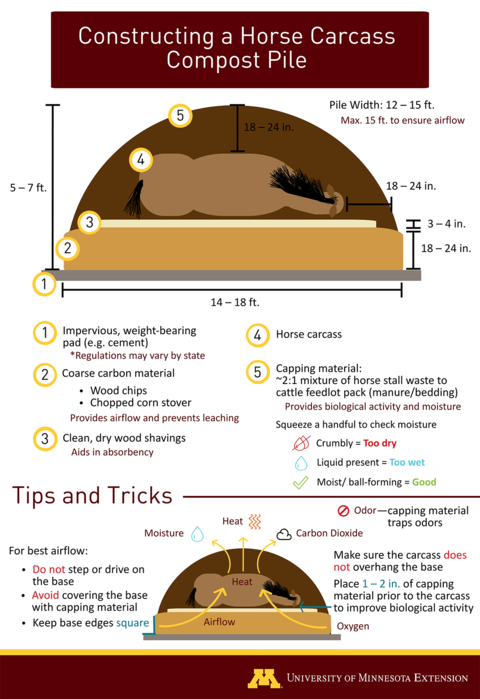

Mortality composting is an economical, environmentally safe and bio secure practice. University of Minnesota documented a > 94% reduction in sodium pentobarbital after 6 months of composting. Though residues remain, equine mortality compost piles show promise for carcass disposal. (Lochner et al. 2022) See the info-graphic to the right, developed by Minnesota Extension. More detailed information, including an instructional video are available at: Constructing and managing a horse carcass compost pile.

Mortality composting is an economical, environmentally safe and bio secure practice. University of Minnesota documented a > 94% reduction in sodium pentobarbital after 6 months of composting. Though residues remain, equine mortality compost piles show promise for carcass disposal. (Lochner et al. 2022) See the info-graphic to the right, developed by Minnesota Extension. More detailed information, including an instructional video are available at: Constructing and managing a horse carcass compost pile.

–

Take Home Message

In the essay “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten” Robert Fulghum states “Goldfish and hamster and white mice and even the little seed in the Styrofoam cup – they all die. So do we.” As horse owners we must consider that inevitability. Failing to face the decision to euthanize a horse to relieve pain and discomfort could be considered neglect. In this sense, “death becomes an act of care that starts long before the final moment of euthanasia.” (Srinivasan, 2013)

–

Recommendations:

–

-

Consider life-long commitment before buying and/or breeding.

– -

Investigate carcass disposal options relative to euthanasia method and make a plan.

– -

Make decisions with your head as well as your heart.

_

–

References:

Arluke, A and Sanders, C; Regarding Animals; Temple UP, Philadelphia (1996)

AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition

California Cattle & Horse Euthanasia Guidelines

Cudworth, 2015, E. Cudworth, Killing animals: sociology, species relations and institutionalized violence, Sociol. Rev., 63 (2015), pp. 1-18

Krueger BW, Krueger KA. US Fish and Wildlife Service fact sheet: secondary pentobarbital poisoning in wildlife. Available at: cpharm.vetmed.vt.edu/USFWS/.

Lochner, H., K. Martinson, A. Bianco, M. Hutchinson, M. Wilson, L. Johnston, and K. Dentzman. Owner and Veterinarian Perceptions of Equine Euthanasia and Mortality Composting. Submitted to the Journal of Equine Veterinary Science on December 1, 2020.

Lochner, H., M. Hutchinson, M. Wilson, L. Johnston, A. Bianco, L. Johnston, J Prigge and K. Martinson. Characteristics and Sodium Pentobarbital Concentrations of Equine Mortality compost Piles in the Upper Midwest. J Eq Vet Sc. 114 (2022)

Schuurman, N., A good time to die: Horse retirement yards as shared spaces of interspecies care and accomplishment. J of Rural Studies 57(2018) 110-117.

Shearer, J Anatomical Sites for Livestock Euthanasia, Iowa State University Extension;

Srinivasan, K. The biopolitics of animal being and welfare: dog control and care in UK and India Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr., 38 (2013), pp. 106-119

Turner, T. When All Else Fails, Alternative Methods of Euthanasia; Vet Clin Equine 37 (2021) 515-519.

Constructing and managing a horse carcass compost pile

- Dr. Saundra TenBroeck is Looking Forward to Looking Back after 40 Years of Service - October 10, 2025

- End of Life Issues – Euthanasia:A Horse Owner’s Final Act of Care - October 4, 2024

- Economic Impact Study Indicates the Florida Equine Industry Remains Strong - April 12, 2024