José Dubeux, Igor Bretas, Luana Queiroz, Kevin Trumpp, Camila Sousa, Cleber de Souza, North Florida Research and Education Center – Marianna

Introduction

The Florida Panhandle and neighboring states had a historical snowfall event along with freezing temperatures (14° F) the week of January 21st, 2025. Many livestock producers had planted cool-season forages for grazing, and they had to face the challenges of managing the herd and the pastures during that period. The most common questions we have received were: Are my forages recovering after this snow? How should I manage the grazing animals? Which forage cultivars are more cold-tolerant than others? Snowfall is not a common event in the region, explaining the reasons for concern. In this article, we discuss how cool-season forages respond to temperature change, the potential insulating role of snow protecting plants from freezing temperatures, how to manage the herd and the pastures during the snow event, and the importance of spreading the risks by diversifying the forage species.

–

Growth pattern of cool-season forages as a function of temperature

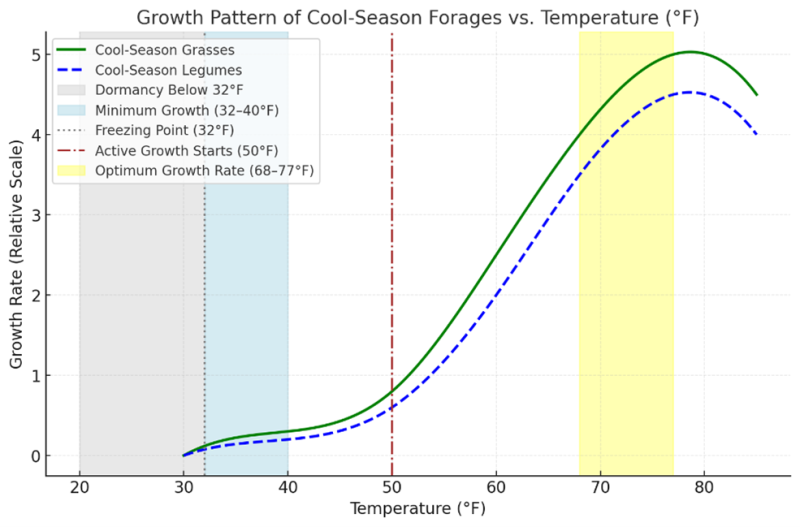

In the Southeastern U.S., cool-season forages are planted in the fall for grazing during warm-season grass dormancy. While they tolerate short periods of subfreezing temperatures, their growth is most vigorous within the optimal temperature range. Cool-season forages begin active growth when soil temperatures reach 50° F, with growth accelerating in the optimal range of 68–77°F. Below 50°F, growth slows significantly, but minimal growth can still occur between 40–50°F. Growth does not entirely stop below 40° F, as some cellular activity allows for limited growth, particularly during warmer daytime conditions. Near 32° F, most forages enter dormancy, halting visible growth while roots and crowns remain metabolically active. Below freezing, active growth ceases completely, and plants rely on stored energy for survival, with cold tolerance varying by species (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A conceptual model based on established growth patterns of cool-season forages described by Moser & Hoveland, (1996). Cool-season grasses and legumes respond similarly to temperature changes.

–

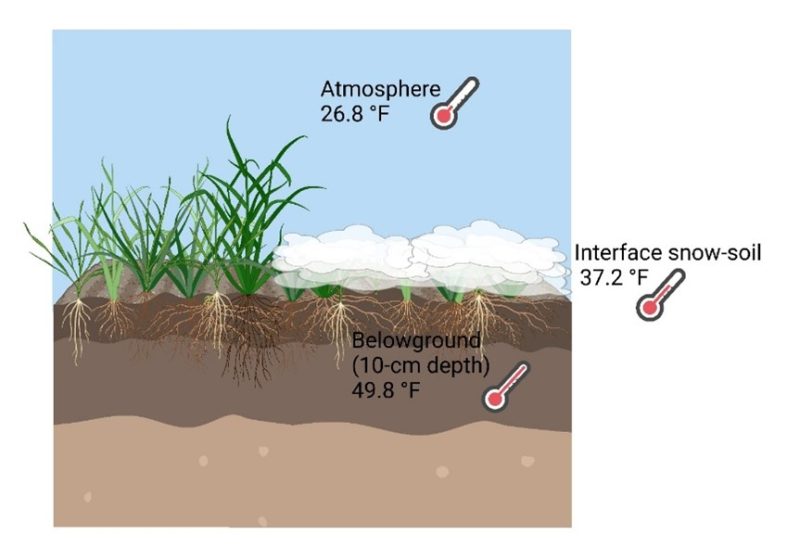

Despite the growth interruption of below freezing temperatures, snow insulation might protect cool-season forages from freezing temperatures and wind chill by acting as a natural insulator (Sheaffer and Drewitz, 2023). Snow insulation buffers soil and plant crown temperatures, shields against freezing winds, retains moisture, and moderates temperature fluctuations, preventing sudden freeze-thaw damage. The extent of its protection depends on snow depth, duration, and the forage species involved. While snow can be beneficial, prolonged extreme cold or insufficient snow cover can still harm plants, particularly less cold-tolerant species. Proper pre-winter management ensures better forage survival under snow. In fact, our team placed a thermometer to measure the temperatures above the snow (air), in the snow-ground interface, and belowground in the recent snow event in Marianna, FL (Figure 2). As indicated in the figure, as we moved down the thermometer, the temperatures got warmer, showing the insulation effect of the snow cover and the soil.

Figure 2. Effect of the snow cover on soil temperature. Measurements taken on January 22, 2025, Marianna, FL. Created with BioRender. Trumpp, K. R. (2025). https://BioRender.com/d97m596

–

Cold-tolerant forage species and snow insulation effect

Several species are commonly selected for winter forage production in the Southeastern U.S. In fact, farmers and producers usually consider different characteristics when deciding the species they will plant on their land, and these are related to the use such as grazing, hay, or as a cover crop. On the other hand, one of the most important forage characteristics is the tolerance to low temperatures. Cold is a stressor that affects the land cover and plant distribution, the forage accumulation, and the overall survivability. The main morphological symptoms of cold stress in forage crops include chlorosis (yellowing), leaf wilting, leaf rolling, lack of vigor, or tissue necrosis (localized death of living tissue) (Adhikari et al., 2022).

Common species utilized and adapted to this region are small grains like cereal rye (Secale cereale L.), wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), oats (Avena sativa L.), triticale (Triticosecale Wittm.), and black oats (Avena strigosa Schreb.). These species are commonly planted in monocultures or mixtures. Other alternatives are annual ryegrass and legumes, such as cold-tolerant diploids and tetraploids ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) and adapted clovers (Trifolium sp.) varieties (Mullenix & Rouquette, 2018). Rye is one of the most used small grains, especially for grazing conditions. Rye and triticale are more cold-tolerant than oats and black oats, and typically produce more forage than wheat in Florida. Wheat is also less susceptible to freeze injury than oats and black oats.

In areas where legumes are possible, legume-grass mixtures are preferred over pure legume stands. From the viewpoint of winter survival, the complementarity of species helps provide a more uniform soil cover. Grasses provide an extra winter cover, helping collect snow, which works as insulation to the soil against freezing and thawing, enhancing the legume survival (Smith, 1964). Annual clovers such as the arrowleaf (Trifolium vesiculosum Savi), ball (Trifolium nigrescens Viv.), crimson (Trifolium incarnatum L.), and red (Trifolium pratense L.) have a good cold tolerance. When plants are injured, their growth is reduced, and the leaves usually turn yellow. Therefore, including different forage species and diversifying the system works as insurance for farmers. This provides greater stability against weather variations, as one species could be more tolerant to a stressor and will compensate for the damage or loss from other species.

We monitored the evolution of a pasture with cover crops composed of oats and crimson clover for seven days after the snowfall event in Marianna, Florida, in January 2025. The cover crops were visually affected by the low temperatures. Oats showed necrosis at the leaf tips on the 5th day after the snowfall event (Figure 3), and this damage was less severe in oat fields that received nitrogen fertilization. Considering that temperatures reached 14°F, we consider that the snow cover actually helped to reduce the damage.

–

We also observed plots planted with oats intercropped with legumes or oats intercropped with ryegrass. The legumes showed no visible signs of damage, while oats exhibited necrosis and leaf rolling in all planting scenarios (Figure 4). This evaluation highlights the importance of intercropping in winter for pasture resilience under extreme weather conditions.

–

Management Practices

Effective management practices during and following a snowstorm can significantly affect grazing systems and may require adjustments to short-feeding strategies. It is valid to recognize that snow cover provides insulation to forages (Nelson et al., 2012), often creating a more stable environment than fluctuating temperatures and strong winds. Several important considerations must be considered when managing a grazing system during such conditions. For example, the application of fertilizer on frozen ground is generally ineffective and may result in nutrient loss through runoff (Schneider et al., 2018). Additionally, in regions experiencing severe winter conditions, implementing feeding strategies may require more time, highlighting the need for well-structured early grazing plans. One potential approach during periods of snow cover is the temporary feeding of hay. Another effective strategy to consider is low-cost bale grazing, which has demonstrated success in sustaining beef cow-calf operations in northern states (USDA-NRCS, 2023; Undi and Sedivec, 2022). Establishing a designated sacrifice area for livestock can be advantageous in promoting pasture recovery when applicable. In cases where such an area is unavailable, it is beneficial to vary hay/bale-feeding locations and mineral trough placements. This approach not only enhances nutrient distribution but also helps alleviate overcrowding in specific pasture areas and mitigates nutrient loss during snowmelt runoff (Smith et al., 2011). In summary, managing grazing effectively during snowstorms relies on understanding the impact of snow cover and adjusting feeding and fertilization strategies accordingly. By planning ahead and adapting to winter conditions, producers can secure feed for livestock while protecting their pastures, thus ensuring a more resilient grazing system during challenging weather scenarios.

–

Take-Home Message

Diversifying the cool-season forage species helps to increase the resilience of pasture systems in extreme weather events. Snowfall might help to protect against extreme low temperatures, but conditions vary depending on the snow depth, duration of the event, and forage species involved. Feeding hay during the pasture recovery phase might speed up the regrowth while sustaining livestock health. Warmer temperatures are expected in the next few weeks, which should accelerate pasture recovery.

–

References

-

Adhikari, L., Baral, R., Paudel, D., Min, D., Makaju, S. O., Poudel, H.P., Acharya, J. P., Missaoui, A. M., 2022. Cold stress in plants: strategies to improve cold tolerance in forage species. Plant Stress, 4, 100081.

– -

Moser, L. E., & Hoveland, C. S. (1996). Cool-Season Grass Overview. In L. E. Moser, D. R. Buxton, & M. D. Casler (Eds.), Agronomy Monographs (pp. 1–14). American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America.

– -

Nelson, C.J., Redfearn, D.D. and Cherney, J.H., 2012. Forage harvest management. Conservation outcomes from pastureland and Hayland practices: Assessment, recommendations, and knowledge gaps, pp.205-256.

– -

Schneider, K.D., A. Thiagarajan, B.J. Cade-Menun, B.G. McConkey, and H.F. Wilson. 2018. Nitrogen Loss in Snowmelt Runoff from Non-Point Agricultural Sources on the Canadian Prairies. In: Lal, R. and Stewart, B.A., editors, Soil Nitrogen Uses and Environmental Impacts. 1st ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL : CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018. | Series: Advances in soil science. p. 73–94

– -

Sheaffer, C. & Drewitz, N. (2023). Let it snow! Minnesota Crop News. University of Minnesota Extension.

-

Smith, A., J. Schoenau, H.A. Lardner, and J. Elliott. 2011. Nutrient export in run-off from an in-field cattle overwintering site in East-Central Saskatchewan. Water Science and Technology 64(9): 1790–1795. doi: 10.2166/wst.2011.747.

– -

Undi, M., and K.K. Sedivec. 2022. Long-term evaluation of bale grazing as a winter-feeding system for beef cattle in central North Dakota. Applied Animal Science 38(3): 296–304. doi: 10.15232/aas.2021-02248.

– -

United States Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2023. Bale Grazing: Success as Cattle Feed Themselves for Better Soils and Winter Ranch Life.

- Grazing Cover Crops is a Triple Win! - August 15, 2025

- How are My Cool-season Forages Recovering from the Snowfall and Low Temperatures? - January 31, 2025

- Integrated Crop-Livestock Systems Improve Soil Health - July 26, 2024