Chaein Na and Diane Rowland, UF/IFAS Agronomy Department

University of Florida researchers conducted an extensive field trial recently to investigate the hidden half of the corn plant, namely the roots. An extensive root system is beneficial for nutrient scavenging and exploration of deep water sources in the soil. This is important for many regions in Florida, where nutrient leaching from agricultural areas causes numerous environmental concerns, plus increased fertilizer costs when supplemental applications must be made after heavy rains. Although the importance of the root system to plant growth and development should not be ignored, the great difficulty involved in studying and measuring roots in the field has led to a general lack of information and understanding at the field scale. However, the recent development of systems that can take images of crop roots in the field without disturbing the plant has opened up a new underground world.

Figure 1. Before mini-rhizotron tube was inserted, a GiddingsTM soil drilling rig creates a hole for the tube.

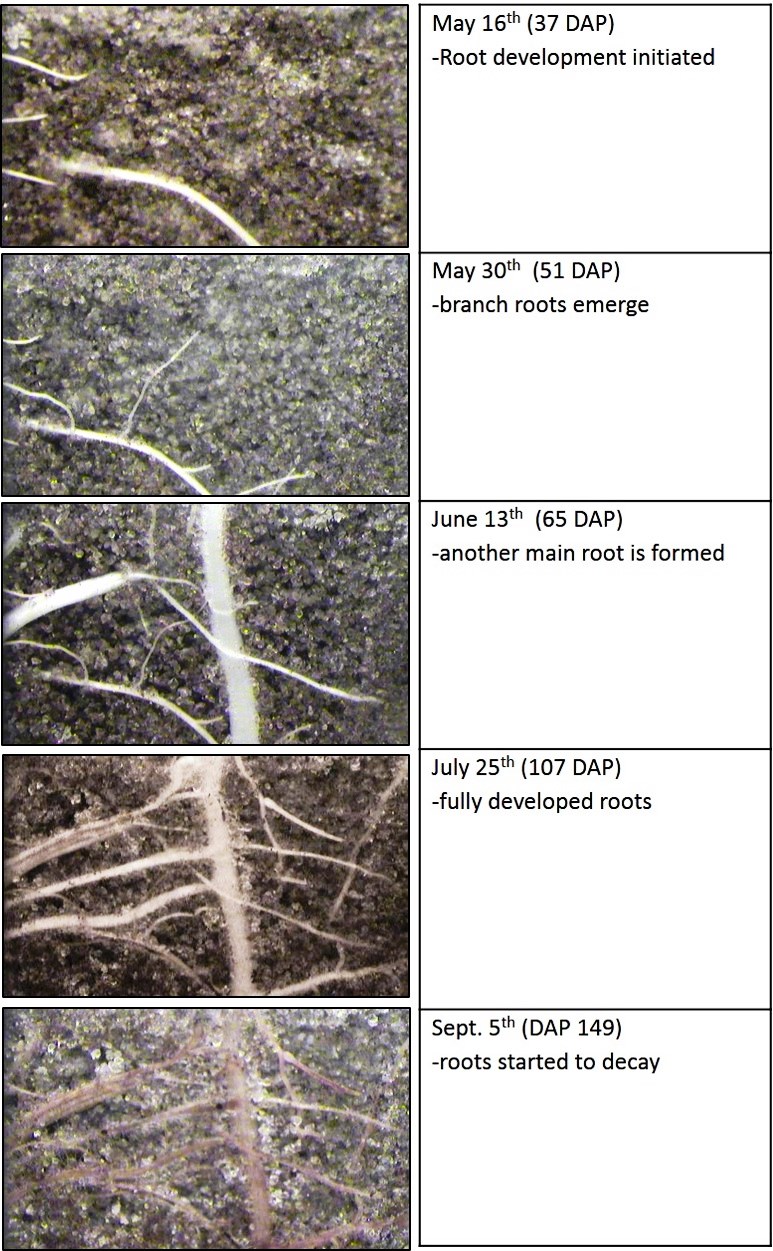

Silage corn is a major feedstock for the Florida dairy industry, but like most crops, there is almost no information available about its root architecture and how it develops over the season. Recently, a field trial was set up at the Plant Science Research and Education Unit (PSREU) near Citra, Florida to investigate seasonal root development in silage corn. A commercial hybrid, ‘Agratech1023VIP’, was sown April 10, 2014. Transparent 6 foot long tubes (mini-rhizotrons) were inserted in the row at a 45 degree angle to the soil surface at three weeks after planting (figure 1). As the roots of the plant developed, they grew over the tube which allowed digital pictures to be taken of most of the root system down to almost three feet (figure 2). A locking mechanism on the tube allows the camera to capture images at the same locations over time, so corn root images were collected on five dates – May 16th, 30th, June 13th, July 25th and Sept 5th (figure 3).

Figure 2. Root image is being captured; Dr. Na is monitoring captured images (left), Mr. Carter Lambert, a UF student, is inserting camera in to the tube accordingly (right).

Some interesting facts were found: the depth of the root system was over 20 inches by 30 days after planting (DAP) and reached the end of the tube (about 3 feet) by 60 DAP. The total root length produced averaged just 2 tenths of an inch of root for every square inch of soil in May but increased to over 3 inches of root for every square inch of soil by July (100 DAP). This root length was not equally distributed over the three feet of soil depth monitored, but the bulk of the root system was concentrated in the top 16 inches of soil throughout the season. Just like the plant above the soil, the roots clearly began to decay by September as the crop dried down prior to harvest.

Figure 3. Example of seasonal development of corn roots in same location: 7 inches from the soil surface.

Using this type of information about corn root system development, growers can more precisely plan fertilizer and irrigation applications to avoid nutrient leaching in Florida. Also, by assessing differences in cultivars for root system growth, growers can tailor choices to match field conditions. Clearly, the presence of deep roots in this cultivar by 60 DAP indicated it has the potential to access deep nutrients and water that might be beneficial during the grain filling period of silage corn.

- Rapid Response Team Deployed to Investigate Peanut Collapse - September 21, 2018

- Developing a “Stress Breathalyzer” for Peanuts - April 13, 2018

- Peanut Nodule Analysis to Assess Crop Health - August 18, 2017