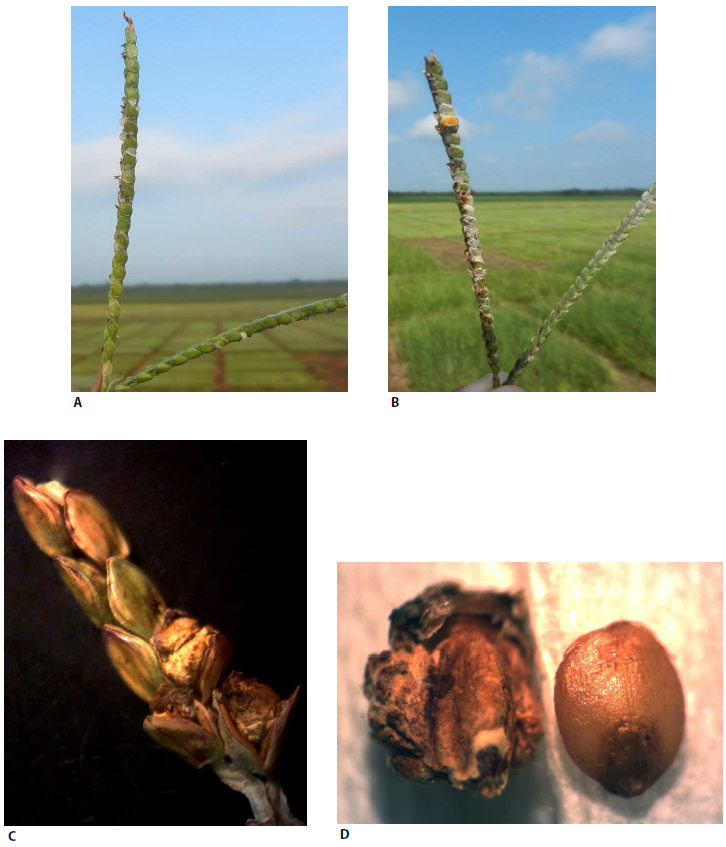

Ergot infected Argentine bahiagrass seedheads on the left and center, normal seedhead on the right. Photo credit: Doug Mayo

Several calls have come in to the Jackson County Extension Office recently from producers regarding something unusual in their “Argentine” bahiagrass fields. A parasitic fungal disease called ergot (Claviceps paspali) is growing on the seedheads (racemes) of Argentine bahiagrass, in fields that have been allowed to reach maturity for seed production or delayed hay harvest. The weather conditions lately have certainly been favorable for fungal disease: cloudy days, high humidity, and frequent rainfall. If you have Argentine bahiagrass pastures, you should be familiar with the symptoms of this fungal disease, so you can monitor it and manage accordingly. There are two major concerns with ergot: 1) ergot spores contain a toxin that affects livestock and 2) ergot decreases seed production. The fungus actually prevents flower fertilization and seed formation, so the main issue for seed producers is just a mild to serious loss in overall yield. Ergot toxicity from bahiagrass is very rare, but could become an issue under the right conditions.

Ergot Identification

Argentine bahiagrass is much more commonly infected with ergot than the “Pensacola” cultivars (Tifton-9, TifQuik, UF Riata). The “Pensacola” cultivars on the other hand are more susceptible to dollar spot (Sclerotinia homoeocarpa), which is a fungal disease of the leaf tissue. Ergot spores are spread by wind, insects, or animal movement. The fungus first infects the bahiagrass flowers and then grows in place of the seed.

Ergot frequently infects grasses in the genus Paspalum (bahiagrass) in the southern United States. The infection cycle begins with sexual spores (ascospores) spread by wind or possibly insects. The fungus infects the pistil of the flower at the time of flowering by colonizing the styles of susceptible plants, and a few days later the content of the ovary is replaced by fungal tissue. The sign of ergot infection appears at flowering (anthesis) when a sugar-rich honeydew (exudate) is produced on infected flowers (florets). The honeydew makes seed heads feel sticky, and the exudates contain the asexual spores (conidia) that are responsible for initiating secondary infections (Fig. 1 A and B). Disease development is correlated to environmental conditions of high humidity, cloudy days, and warm temperatures, after which the disease cycle ends by forming a mass of dark fungal tissue (sclerotium) that replaces the seed and forces the glumes apart (Fig. 1 C and D). Additionally, ergot-infected seed contains alkaloids that are poisonous to animals. Ergot Resistant Tetraploid Bahiagrass and Fungicide Effects on Seed Yield and Quality

FIGURE 1 Ergot (Claviceps paspali ) in ‘Argentine’ bahiagrass: (A) early stage of honeydew development at anthesis; (B) dried honeydew in approximately 40% of the seed head and saprophytic fungi growing in a seed head postanthesis; (C) seed head at the time of harvest with three florets whose seed was replaced by ergot (note how the fungal tissue forced the glumes apart) while the other florets were not affected by the fungus; (D) normal caryopsis fully developed, right, and caryopsis replaced by ergot, left. Source: Ergot Resistant Tetraploid Bahiagrass and Fungicide Effects on Seed Yield and Quality

Toxicity

Ergot toxicity is not a common issue with grazing livestock, but is something worth monitoring in Argentine bahiagrass fields, at this time of year. The fungus only affects the seedheads, so the rest of the plant is nontoxic. With normal, rotational or continuous grazing, the percentage of mature seedheads in a given pasture is fairly limited. The greatest concern is turning livestock in to graze a pasture with a high percentage of mature seedheads in mid to late summer. This might be an issue in a field where seed production or hay production was abandoned and instead utilized for grazing. Or perhaps a pasture that has not been utilized for several weeks, that has become more mature than normal in a rotational grazing system.

The key to livestock poisoning is the amount of toxic spores that are consumed. The old adage, “The solution to pollution is dilution” is certainly true with livestock. The key is to avoid long, continuous exposure, or feeding toxins in a high percentage of the diet.

Intake of ergot bodies should be <0.1% of the total diet, and concentrations of ergot alkaloids should be <100 ppm in the total diet. Ergotism can be controlled by an immediate change to an ergot-free diet. Merck Vet Manual

The NRCS Bahiagrass fact sheet contains the following statement:

Caution: Seed heads of the cultivar ‘Argentine’ are often infected by ergot (Claviceps paspali). Pregnant mares can experience abortion problems, if they eat large quantities of infected seed heads. Also, ingestion of infected seeds can produce toxic effects in cattle. USDA NRCS – Plant Materials Center

Animals consume ergot by eating the spores (sclerotia) present in contaminated feed. All domestic animals are susceptible, including birds. Cattle seem to be the most susceptible. The responses of animals consuming ergot are usually quite variable and are dependent on variations in alkaloid content, frequency of ingesting ergot, quantity of ergot ingested, climatic conditions under which ergot grew, the species of ergot involved, and the influence of other impurities in the feed such as histamine and acetylcholine. Two well-known forms of ergotism exist in animals, an acute form characterized by convulsions, and a chronic form characterized by gangrene. A third form of ergotism is characterized by hyperthermia (increased body temperature) in cattle, and a fourth form is characterized by agalactia (no milk) and lack of mammary gland development, prolonged gestations, and early foal deaths in mares fed heavily contaminated feed. Which form of ergotism is manifested depends on the type of ergot consumed and the ratio of major toxic alkaloids present in the ergot: ergotamine, ergotoxine,and ergometrine. Claviceps purpurea, the common cause of ergot in North Dakota, is usually associated with gangrenous ergotism. Claviceps paspali, an ergot of Paspalum species of plants (bahiagrass & dallisgrass), is most commonly associated with central nervous derangement. The responses of animals consuming ergot are usually quite variable and are dependent on variations in alkaloid content, frequency of ingesting ergot, quantity of ergot ingested, climatic conditions under which ergot grew, the species of ergot involved, and the influence of other impurities in the feed such as histamine and acetylcholine. Ergot as a Plant Disease

Symptoms of Bahiagrass Staggers

The same ergot fungus (Claviceps paspali) that affects Argentine bahiagrass also effects dallisgrass, that is more common in other parts of the South. The following is a description of the symptoms of egrot toxicity from the same fungus that also affects Argentine Bahiagrass.

Clinical signs of Dallisgrass Staggers involve the animal’s nervous system. In the very early stages of the disease, the only sign seen may be trembling of various muscles after exercise. As the disease progresses, muscle tremors worsen so that the animal becomes uncoordinated and may show continuous shaking of the limbs and nodding of the head. When forced to move, this severely affected animal may stagger, walk sideways, and display a “goose-stepping” gait. Incoordination can be severe enough that the animal will fall down when attempting to walk. Some animals may be found down and unable to stand. Diarrhea may also be noted in some affected animals. Death can occur in severe cases, especially in scenarios where cattle are naïve to grazing dallisgrass. There is no cure for ergot poisoning, but removing cows from infected pastures when symptoms are first noticed usually results in uneventful recovery in three to five days. Mowing seedheads to prevent animals from grazing them helps prevent the problem from occurring. Ergot toxicity from dallisgrass hay is very uncommon since the total intake of hay forage dilutes any ergot contained in the hay. Ergot Poisoning and Dallisgrass Staggers

Management of Ergot in Bahia

—

Information sources used for this article:

Ergot Resistant Tetraploid Bahiagrass and Fungicide Effects on Seed Yield and Quality – Rios, E., Blount, A., Harmon, P., Mackowiak, C., Kenworthy, K., and Quesenberry, K. 2015. Plant Health Progress doi:10.1094/PHP-RS-14-0051.

Ergot as a Plant Disease – NDSU – Marcia McMullen, Extension Plant Pathologist & Charles Stoltenow, Extension Veterinarian

Ergot Poisoning and Dallisgrass Staggers – Dr. John Jennings, Extension Forage Specialist – University of Arkansas

Bahiagrass Plant Fact Sheet – Houck, M., 2009. USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Louisiana

Ergotism – Merck Veterinary Manual

- Ranch Record Keeping for Annual Analysis & Innovation - January 23, 2026

- Friday Feature: 2026 Farm Dog of the Year - January 23, 2026

- 2025 Weather Summary and 2026 1st Quarter Outlook - January 16, 2026