Amanda Masholie, Sustainable Ag & Small Farms Agent-Walton County

As a highly adapted grazing animal, horses encounter challenges when high quality forages are not the foundation of their diet. Many horses kept in confinement develop behavioral issues such as cribbing; where they chew and grasp the stall or fence while sucking air. Cribbing is induced by stress, boredom, and inadequate forage access. Cribbing is a very bad habit in horses that leads to unwanted health challenges and decreased economic value of the animal. This is why turn-out and access to a high-quality forage system is essential.

Forage is a vital fundamental component of keeping horses, and horse owners must understand the significance of pasture management. To be successful with any type of grazing animal, one must learn to be a grass farmer first!

Horses have very significant forage intake needs to meet their basic nutrient requirements. A single horse will ideally consume approximately two percent of their body weight per day in forage. Pasture must be viewed as a major nutrient source by horse owners. The average 1000-pound horse can collectively consume and waste approximately three tons of forage dry matter during a six-month grazing season (LeMaster, Cassie W. 2025). It is not unreasonable for healthy mature horses to be maintained on quality pasture alone during the pasture’s growing season. This allows grain and hay to be reduced which leads to significant cost savings for the equine owner and prevents obesity and overfeeding of their equine partners.

Grazing systems are vital to proper care and management of horses and should be adapted based on the land area, water source, and other resources available to the horse owner. Florida’s climate is such that quality forages can be grown nearly year-round; however, farm planning and management are key to making this happen.

–

TYPES OF GRAZING SYSTEMS

Two common types of grazing systems seen in equine operations are continuous and rotational grazing systems:

Continuous grazing systems are the most common practice, where horses are housed on a single pasture for extended periods of time. This system has disadvantages, as it’s difficult to manage grazing intensity and duration. Horses are selective grazers and prefer young immature plants. They will repeatedly return to the same areas of pasture to graze tender new growth. Selective grazing, and the preference to avoid manure piles creates areas of overgrazing. In turn, underutilized taller mature forage patches will develop within the scope of the forage system. Consistent overgrazing leads to thinning the forage stands, which allows for weeds to take over, further reducing forage productivity and presence. If pastures are not properly managed, forage availability is greatly reduced. Continuous grazing can work in situations where there is an adequate supply of pastures land that will support the number of horses grazing, but additional intense management may be required in times of drought, diminished forage growth, and to battle the nature of the equine species as selective grazers.

Rotational grazing requires a more intensely managed system, where larger pastures are subdivided into smaller paddocks. Horses are moved between paddocks during the grazing season to allow periods of forage rest and re-growth. The rest and re-growth periods lead to increases in forage production, improves pasture use, and provides more forage mass for horses to graze (Sollenberger et al. 2018, Vendramini and Sollenberger 2020). The resting period which is absent in continuous grazing lets forages develop stronger root systems and grow new leaf structure and surface area.

It is vital to accept that horses are selective grazers, but when concentrated on smaller areas, they graze more uniformly. In a rotational grazing system, as the number of paddocks increase, so does the efficiency of forage utilization as there is less waste. (Bennett, Laura 2025)

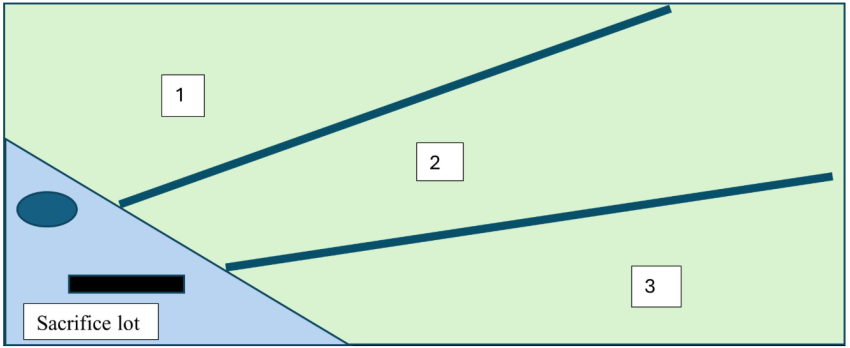

An example of a three-paddock layout with a sacrifice lot in the corner that allows access to water and feed troughs. Credit: Laura Bennett, UF/IFAS – Rotational Grazing Management for Horses

–

IMPLEMENTATION

To implement rotational grazing, you must divide the large pasture into smaller paddocks with access to a common management area (sacrifice lot) which contains shelter, water, minerals and feed sources. Horses should always have access to the sacrifice lot no matter what paddock they are grazing.

To use this system, the farm manager must identify paddocks that are ready to be grazed, which will be indicated by forage heights of 6 to 8 inches for bahiagrass. The horses are then allowed access only to that one paddock and with the remaining paddocks closed off. The horses are allowed to graze that paddock until forage height is 3 to 4 inches tall (take half-leave half rule). Once that desired forage height is reached, the next paddock with 6 to 8 inches of forage height is opened and the horses are moved which allows the previous paddock to be rested for at least two weeks or until forage regrowth reaches 6 to 8 inches in height.

After horses are moved, the paddocks can be mowed at a height above 3 inches to maintain uniformity and to help control weeds. Dragging of the pastures should also be incorporated into the paddock rotations especially during summer months. Managers can drag paddocks with a harrow or length of chain-link fence to break up manure piles. Breaking up the manure piles helps promote more even grazing in future rotations and also gives the sun time to kill parasite larvae. Parasite control is most effective when temperatures are above 90 degrees Fahrenheit and there is no precipitation. After dragging, managers should allow the sun about seven days to kill the parasite larvae. (Bennett, Laura 2025).

–

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

In conclusion, equine forage systems are best managed using rotational grazing, which involves moving a group of horses between several managed paddocks on a regular basis. Measuring forage height is the best tool for determining speed of rotation because it accounts for environmental conditions (temperature and rainfall) and soil fertility. After the forages are grazed to the ideal height, the paddock is rested. During the resting period the paddock is managed as needed with mowing, aeration, dragging, fertilization, and/or herbicides and then allowed to regrow. The most important part of this system is the grass recovery period which takes place while the horses are on other paddocks in the system. Rotational grazing can meet the needs of horse farm managers in the same way it works well for many other types of grazing livestock. No matter how you lay out your paddock system, the key is allowing recovery time for forages to re-grow. Successful horse owners and managers must learn to become a grass farmers. Rotational grazing systems are an excellent management strategy to maximize the efficiency of the forage system for selective grazing equine.

–

References:

Bennett, Laura 2025. “Rotational Grazing Management for Horses VM268, 2/25” EDIS.

LeMaster, Cassie W. 2025. “Rotational Grazing for Horses”.

Sollenberger, L.E., J.M.B Vendramini, J.C.B. Debux, and M. Wallau 2018. “Grazing Management Concepts and Practices: SS-AGR-92/AG160, rev 5/2018.” EDIS 2018 (4).

- Considerations for Horse Owners Responding to Recent EHV-1 Outbreak - November 21, 2025

- Agricultural Conservation Easement Webinar – December 4 - November 21, 2025

- Equine Health Alert: Mosquito-Borne Viruses Are Concerning To Florida Horses - September 12, 2025