Brett Capra, University of Florida, Senior in Animal Sciences & UF/IFAS Extension Intern with Kalyn Waters, UF/IFAS Extension Holmes County

Florida cattle ranchers are really grass farmers. The cattle are the cash crop, but managing the soil fertility and forage yield are key to efficient cattle production. Credit: Kalyn Waters, UF/IFAS

In the Southeast, every rancher is also a “grass farmer!” Our primary resource we depend on is forage. However, Florida pastures don’t usually have a lot of natural nutrients in the soil. When animals heavily graze continuously, the soil can lose even more nutrients, especially nitrogen (N), which makes it harder for the grass to grow. By learning how to recycle nutrients back into the soil, you can improve pasture growth, keep your soil healthy for the long run, and spend less money on off-farm purchased fertilizers.

–

Plant Litter

Plant litter (such as dead grass and leaves) is an important way to return nutrients to the soil, in addition to the urine and manure produced and spread by the grazing animals. This system is how nutrients are nutrients are recycled and can affect which plants grow best in your pasture. In well-managed pastures, animals eat about 70% of the grass they produce, leaving around 30% behind as litter. If animals graze too heavily (intensive grazing), there’s usually less litter left, but the litter tends to have a higher nitrogen content than forages with limited grazing.

Tropical grasses, common to Florida, break down slowly because they have a high carbon (C)-to-nitrogen(N) ratio. Because tropical grasses have a lower protein content (Less N) with a higher percentage of fiber (C), the litter decomposes more slowly than than annual forages such as ryegrass. When you have a high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, the litter decomposition process actually competes with pasture grass roots for soil nitrogen—a problem called nutrient immobilization, which can lead to reduced pasture growth over time.

One way to improve the C:N ration in your pasture soils are to incorporate warm-season annual forage legumes into your grass pastures. Legumes convert airborne N into a form usable by plants. Dr. Gerald Wayne Evers, Texas A&M, explains this process in his article called, Nitrogen Fixation. “A legume plant’s ability to use nitrogen from the air is the best known benefit of growing legumes but the least understood. Approximately 79% of the air is nitrogen gas. However, it is not in a form that plants can use. In reality it is not the plant that removes nitrogen from the air but Rhizobium bacteria which live in small tumor like structures called nodules on the legume plant roots. These bacteria can take nitrogen gas from the air in the soil and transform it into ammonia (NH3) that converts to ammonium (NH4) which can be used by the plant. This ammonium is the same form as in ammonium nitrate (34-0-0) and ammonium sulfate (21-0-0) fertilizer. The nitrogen fixation (N2-fixation) process between the legume plant and rhizobia bacteria is referred to as a symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationship. Each organism receives something from the other and gives back something in return. Rhizobia bacteria provide the legume plant with nitrogen in the form of ammonium and the legume plant provides the bacteria with carbohydrates as an energy source. The rate of N2-fixation is directly related to legume plant growth rate.”

Because of this symbiotic relationship, legumes also improve the quality of the forage consumed by livestock and the litter created which boosts the productivity of your forage grasses. However, keeping legumes in your pasture can be challenging, because grazing animals will selectively graze them at a higher rate than the grasses, so they work best in a rotational grazing system. Legumes also typically require a higher pH and phosphorous (P) and potassium (K) levels than grasses to mature and produce seed for next year’s crop. In addition, legumes are broad-leafed plants and not grasses, so herbicides used to control broad leafed weeds will often injure of kill the annual forage legumes as well. Balancing weed control in a mixed forage system is complicated, but forage legumes can be reintroduced from seeds to pastures once weeds are under control.

–

Grazing

Manure and urine (excreta) from grazing animals are the major way nutrients are recycled back to the soil. Nutrients taken in by livestock, whether from grazing or supplemental hay and feed, are excreted based on where they spend most of their time. These nutrients are cycled back at a surprisingly high rate, with approximately 70-80% of the nitrogen (N), 60-85% of the phosphorus (P), and 80-90% of the potassium (K) in being excreted back to the soil. The problem is, animals don’t spread those nutrients evenly across the pasture. Cattle often hang out in certain spots like shady areas, near water, or by the gate watching for the next round of supplemental feed. So, congregating areas receive higher amounts of nutrients, while other parts of the pasture with actively grown forages receive less. One way to control this better is by utilizing rotational grazing. The more frequently cattle move through smaller paddocks the better the excreta distribution across the farm. With more even nutrient distribution, more of the forages in the pasture benefit.

–

Hay or Forage Harvesting

The sun sets on a successful day of bailing hay. Producers will need to replace nutrients in the soil that are lost when bales are removed from the field and fed in other locations. Credit: Kalyn Waters, UF/IFAS

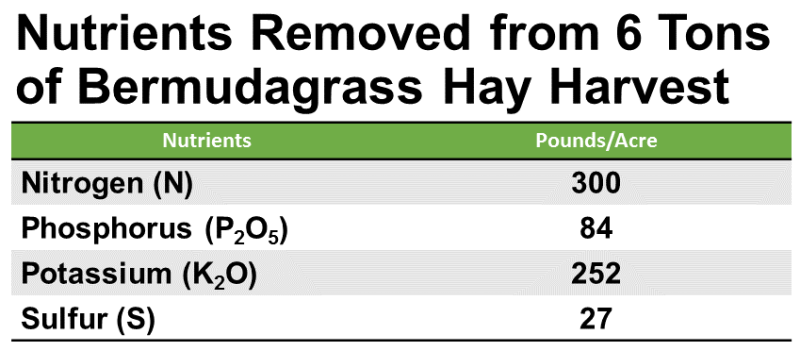

Grazing, animals excrete a good portion of the nutrients back into the soil, but hay harvest hay is a different story. The forage, and all the nutrients it contains are removed from the field entirely. The only nutrient recycling comes from a limited amount of leaf litter. That means you’re mining nutrients like N-P-K out of the soil with each hay harvest. Table 1 below from the publication, Bermudagrasses in Georgia, shows how much N-P-K is removed from harvesting 6 tons of Bermudagrass hay over a growing season.

Source: Table 1: UGA publication – Bermudagrasses in Georgia

–

Unlike grazing, haying requires a more active approach to keeping the soil healthy and productive. Unless you replace what’s lost through commercial fertilization or organic soil amendments like manure or chicken litter, the soil can be depleted fairly rapidly. Soil nitrogen and potassium move or leach through the soil with rainfall. To help manage nutrient leaching, we utilize split applications through the season in the spring and after all but the last hay harvest. In the example provided for the Bermudagrass hay above, if you expect to make four hay cuttings each year you would divide that into four applications of 75#N – 21#P – 63#K – 7#S. Since hay yields varies considerably year-to-year based on rainfall and management, annual soil testing is recommended for hay fields to ensure that adequate major and micro-nturients are replenished in the soil each year.

When soil fertility drops, your forages won’t grow or persist well, and that can hurt your bottom line. You can improve soil fertility and health in your pastures by adjusting your grazing methods, changing stocking rates, strategic fertilization, and planting warm-season legumes in your pasture. These changes help your grass grow better, and keep your pastures productive for the long haul.

–

For more information, use the following publication link:

Nutrient Cycling in Pastures – Range Cattle Research & Education Center – University of Florida – Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

- Big Doe Contest Returns for 2025: A Growing Thanksgiving Tradition - November 14, 2025

- UF/IFAS Extension Panhandle Cattlemen’s College Announces Scholarship Opportunity for Florida Youth – Application Deadline September 15 - August 29, 2025

- Foot Rot Prevention and Treatment for Cattle - August 15, 2025