As the hot days of summer seem to be winding down, we look ahead at ensuring cattle have adequate nutrition in the late fall and winter months. Winter feeding represents one of the largest expenses for cow-calf operations, making accurate hay planning essential. Determining the right amount of hay involves understanding hay quality, quantity, testing, variety, and balancing with supplementation. A practical approach to planning for your hay needs can help alleviate issues later in the season.

Hay quality directly impacts how much cattle consume and the nutrients they receive. High-quality hay provides more energy and protein per pound, reducing the need for costly supplements. Conversely, low-quality hay can lead to weight loss, poor body condition, and reproductive issues if not properly balanced.

–

Key factors influencing hay quality include:

- Forage species (e.g., legumes like perennial peanut vs. grasses like bahia or Bermuda)

- Maturity at harvest (immature forage = higher digestibility)

- Storage conditions (weathered hay loses nutrients)

- Harvest management (rain damage reduces energy and protein)

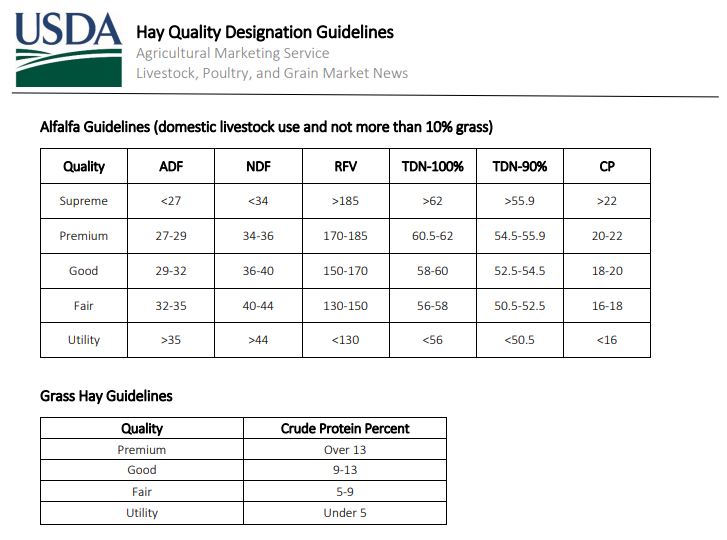

Forage quality is typically expressed in terms of the percentage of Crude Protein (CP) and Total Digestible Nutrients (TDN). For example, Mississippi State University explains that beef cows in late gestation require about 8–10% CP and 55–60% TDN. If hay falls below these levels, supplementation is necessary.

–

Hay Testing

The only way to know hay’s nutrient content is through laboratory analysis. Using “book values” or last year’s results can lead to costly mistakes. Here’s how to test hay properly:

- Sample by lot: A lot is hay from the same field and cutting.

- Use a hay probe: Core 10–15 bales per lot from the round side of round bales or the end of square bales.

- Send to a certified lab: Request analysis for Dry Matter (DM), Crude Protein (CP), ADF/NDF (fiber), and TDN.

- Interpret results: Compare hay nutrient values to cattle requirements for their stage of production.

–

Testing allows producers to:

- Match hay to animal needs (e.g., best hay for lactating cows or growing cattle)

- Identify supplementation needs

- Reduce feed costs by avoiding unnecessary supplements or wasteful hay distribution.

Determining the amount of hay to feed through the winter can be more of an art than a science. Several factors will influence the calculation of hay needs. These include bale size, herd size, hay quality, and cow production cycle. Our colleagues from West Virginia University provide an in-depth look at hay calculations in the publication: Matching Hay to the Cow’s Requirement Based on Forage Test, but for simpler terms, we look at the following scenario.

Cattle typically consume 2–2.5% of body weight in dry matter daily. For a 1,200-pound cow:

- Dry Matter Intake (DMI) = 1,200 × 0.02 = 24 lbs/day

- If hay is 85% DM, as-fed intake = 24 ÷ 0.90 = 28 lbs/day

–

For 20 cows over 150 days:

- 28 lbs × 20 cows × 150 days = 84,000 lbs (42 tons)

- Add 15–20% for storage and feeding losses: 42 × 1.20 = 50 tons

–

Bale weights vary by size and density:

- 4×4 round bale: 400–600 lbs

- 4×5: 700–1,000 lbs

- 5×6: 1,200–1,700 lbs.

When it comes to types of hay, it’s fairly standard across certain areas of the country. The Southeastern United States typically relies on grass varieties of hay, while the central plains and western states are able to grow legume hay more frequently. Each variety has it’s pros and cons, but can generally be implemented in to a feeding plan based on need. Here is a brief explanation of the different types of hay.

- Legume hays (perennial peanut, alfalfa, clover): High in protein and energy; ideal for lactating cows or young stock.

- Grass hays (Bahia, bermudagrass): Moderate in protein and energy; suitable for dry cows, frequently need supplementation for lactating cows.

- Mixed hays: Offer a balance but require testing to know nutreintcontent

–

Even good hay may not meet all nutrient requirements, especially for energy during late gestation or very cold weather. Supplementation strategies include:

- Protein supplements: Needed when hay CP < 8%. Options include soybean meal, cottonseed meal, or high-protein byproducts.

- Energy supplements: Needed when TDN is low. Use fiber-based feeds like soybean hulls or corn gluten feed rather than high-starch grains to avoid reducing forage digestibility.

- Minerals and vitamins: Always provide a balanced mineral mix; deficiencies in magnesium, copper, and selenium are common in winter diets.

Tools like the UF Hay Balancer spreadsheet can help producers calculate the most cost-effective supplementation plan based on hay test results. More information on how to use the UF Hay balancer can be found in the article, Introducing the New UF Hay Balancer Decision-Aid for Cattle Ranchers.

–

Key Takeaways

- Test every hay lot—don’t rely on guesswork.

- Calculate hay needs based on cow weight, feeding days, and storage losses.

- Match hay quality to animal requirements by stage of production.

- Supplement strategically to fill nutrient gaps without overspending.

Proper planning ensures cattle maintain body condition for higher reproduction rates through the winter and early spring while controlling feed costs.

–

References

Mississippi State University Extension. (n.d.). Hay testing and understanding forage quality.

–

Oregon State University Extension. (2025). How to test hay for nutrient content.

–

Rayburn, E. (2013). Matching hay to the cow’s requirement based on forage test. West Virginia University Extension.

–

Schriefer, G., & Radunz, A. (n.d.). Hay analysis guide for beef cattle: Determining winter feed needs. University of Wisconsin Extension.

–

Little, C. (2019). Supplementing poor-quality hay. Ohio State University Extension.

–

DiLorenzo, N. (2018). Introducing the UF hay balancer decision-aid for cattle ranchers. University of Florida IFAS Extension.

–

Mullenix, K., Thompson, G., & Elmore, J. (2021). Supplementation strategies for cow herds during the winter. Alabama Cooperative Extension System.

- 2026 Santa Rosa CountyRow Crop Production Meeting – January 22 - December 19, 2025

- Hay Quality and Quantity Considerations for Winter Feeding - September 5, 2025

- Managing Lice on Cattle - February 28, 2025