Mauro Venturini, Daniella Heredia, Maria Camila López, Angela Gonella Diaza, North Florida Research and Education Center, and Kalyn Waters, UF/IFAS Extension Holmes County

Introduction

Stress is defined as a physiological response to a threat. Stress and the associated adverse effects impact the economic sustainability of the beef industry. Stress responses involve endocrine, paracrine, and neural systems, and further work is needed to clarify, in detail, the consequences of the different types of stress on the reproductive abilities of beef cattle. Stress negatively impacts the consumption of feed, digestibility, metabolism, and the immune system, or a combination there of. Additionally, stress has direct effects on reproductive performance, such as hormone secretion, the diameter of the ovulatory follicle, and consequently, the pregnancy rates. Moreover, it was demonstrated that stress impairs the maintenance of pregnancy, affecting the uterine environment, embryo development, and maternal recognition of pregnancy (David W. et al., 2019). Thus, stress is considered one of the most important factors of embryo loss after reproductive diseases.

Figure 1: Several studies have shown that stress has a direct negative impact on reproductive performance. Animals with excitable temperaments tend to have reduced heat signs and a reduced pregnancy per artificial insemination.

–

Artificial insemination (AI) is a reproductive biotechnology that allows the enhancement of genetic gain and productivity. Additionally, the use of estrus synchronization allows the restart of ovarian cyclic activity, which increases the proportion of cows getting pregnant early in the breeding season and consequently concentrates the calving distribution, which greatly benefits cow-calf operations’ profitability (Gonella et al., 2021). However, achieving good results during an artificial insemination program depends on many factors that producers must try to control, and if stress affects the reproductive process, clearly, cows experiencing stress will have lower response from an artificial insemination program. Therefore, it is important to implement actions to avoid stressors before starting the breeding program. Consequently, there is an increasing interest in understanding the factors that produce stress in cattle, known as stressors, not only to ensure animal welfare but also to preserve the potential productivity of cowherds.

Stressors can be physical, such as heat, noise, transportation, and food restriction, or physiological, such as weaning, social isolation, or mixing of new groups of individuals, and handling. Depending on the duration of the stressor, it can originate an acute reaction, which prepares the organism for quick responses, or a chronic reaction, starting an adaptation process to minimize the magnitude of strain produced by the stressor, which can reduce physiological functions tied to overall productivity (Chen Y. et al., 2015). Producers also need to consider another important factor: temperament, which refers to animals’ reactivity to humans and the immediate environment (Brown E. et al., 2017). Temperament directly influences stress levels, and more temperamental animals tend to experience an increased response to stressors. Moreover, temperament has a strong genetic component (Fordyce G. et al., 1988), which explains the importance of culling for this trait.

–

Management Stressors

Stress related to management is generally associated with the movement, manipulation, and/or transportation of animals. While these activities are certainly necessary to meet a variety of management objectives, the associated stress must be considered and limited to the extent possible. Good, calm and quiet, animal handling practices and good working facilities optimize animal welfare and reduce stress (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Facilities must be in proper condition to guarantee animal welfare and avoid stress. A. A group of cows being handheld during an artificial insemination program. Cows are calm, and quiet handling is used to avoid stress. B. Heifers During a study at NFREC, groups are assigned during the adaptation period to allow animals to establish social bonds and hierarchy before the insemination program. C. Bad facilities increase the risk of accidents and the stress that animals must suffer during each handling.

–

Nutritional stressors

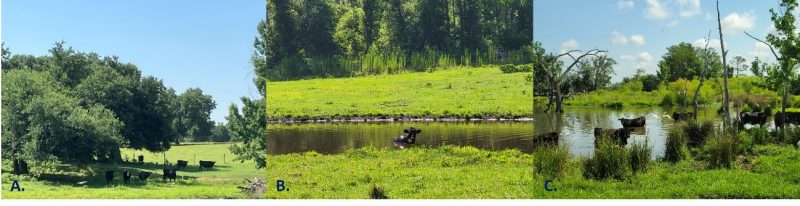

Stress from poor nutrition is a common issue in beef cows (Fernandez-Novo A. et al., 2020). Nutritional stress can be eliminated by ensuring animals have proper access to feed before starting the breeding program. Nutrition is important after AI as well, since subpar nutrition can affect the embryo’s survival and development. For example, a negative energy balance interrupts the normal hormonal cascade that produces ovulation and consequently reduces fertility (Fernandez-Novo A. et al., 2020). In addition, keep in mind that water is also a critical nutritional component, providing animals with access to clean water is very important too (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Poor nutrition is also a cause of stress for cattle. So, animals must have good access to quality food (A) and water (B and C.) during the whole year.

–

Social Stress

Cows can also experience social stress. In fact, several studies have shown that aggressive temperament in heifers can lead to lower pregnancy rates and delay puberty. Moreover, the social system of cattle is highly hierarchical, and this hierarchy influences feed intake, social behavior, relationships between cows, and group creation. Therefore, it is not a good idea to mix animals and create new groups during the artificial insemination program.

–

Environmental stressors

Temperature, humidity, and wind are among the weather stressors that can impact cattle health. Mitigating these stressors can require protecting against extreme environmental conditions (Figure 4). Heat stress, for example, has been associated with lower conception rate and changes in estrus behavior (fewer mounts per cycle and a longer interval between mounts).

Figure 4: Extreme temperatures can affect reproductive performance. Avoid artificial insemination or even natural breeding during the hottest months. However, even if the breeding season is over, it is important to guarantee animals have access to heat mitigation alternatives such as shade (A.) or water (B and C) .

–

Summary

Stressors have a negative impact on reproduction, affecting not only the pregnancy rate but also the embryo’s survival. For that reason, any measure that reduces the stress on animals helps to improve the reproductive results and, consequently, benefits the profitability of the cow-calve operations.

–

References

- Brown E.J., Vosloo A. The involvement of the hypothalamopituitary-adrenocortical axis in stress physiology and its significance in the assessment of animal welfare in cattle. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2017;84.

– - Chen Y., Arsenault R., Napper S., Griebel P., Models and Methods to Investigate Acute Stress Responses in Cattle. Animals. 2015;5:1268-1295.

– - David Wolfenson, Zvi Roth, Impact of heat stress on cow reproduction and fertility, Animal Frontiers, Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2019, Pages 32–38

– - Fernandez-Novo, A., Perez-Garnelo, S.S., Villagra, A., Perez-Villalobos, N., & Astiz, S. (2020). The Effect of Stress on Reproduction and Reproductive Technologies in Beef Cattle-A Review. Animals: an open-access journal from MDPI, 10(11), 2096.

– - Fordyce G., Dodt R., Wythes J. Cattle temperaments in extensive beef herds in northern Queensland. Factors affecting temperament. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1988;28:683.

– - Gonella, A., Ojeda-Rojas, O.A., Bittar, J., Binelli, M. Analysis o the USDA’s 2017 cow-Calf Management Practices Results: Part 1 – Calf Crop and Calving Distribution: AN375/AN375, 11/2021.

- Heat Stress and its Impact on Cattle Reproduction - March 14, 2025

- Fall is Here.Time for Pregnancy Testing Cattle! - September 13, 2024

- How Stress Impacts Cattle Reproduction - March 15, 2024