Marcelo Wallau, Forage Extension Specialist, UF/IFAS Agronomy

Temperatures are forecast to drop significantly this weekend, and we have received several calls about the cold-weather effects on cool-season forages. In fact, despite the La Niña year, which is traditionally characterized by a warmer than average and drier than average winter, we have experienced multiple frosts in North Florida and the Panhandle. Since November, this is the sixth strong cold front to drop temperatures below freezing on one of our research areas. Often, temperatures bounce right back. But this time, temperatures have stayed low for multiple days and have not risen much during the day.

Issues with cold weather are not news. We had a severe cold snap right after Christmas in 2023 that killed many oat pastures (reported here), and snow and low temperatures in 2025, as reported by my colleague Jose Dubeux. So, what is special about 2026? This has been an unusual year, with an extremely dry late summer and fall, resulting in delayed planting and poor development of cool-season forages. We are still in severe drought status, and multiple areas of the state have been designated as “natural disaster”. Moreover, the first frost we got was November 11 and 12, very early in the development of some of those forages.

Many producers are concerned, reporting lower-than-expected performance from their forages. This week, our team checked multiple cool-season pastures across several counties, both irrigated and dryland, at high and low-fertility sites. In general, forages are indeed struggling. We also saw issues on multiple sites where we run a variety of trials, not only related to weather, but also to management.

Figure 1. Rye pasture in North Florida, late-January. Heavy grazing, lower than average rainfall, and cold weather are limiting productivity.

–

Large swings in temperature, as we often see in Florida, can increase the susceptibility to damage. Warmer temperatures will promote growth, and the resulting new tissue is more susceptible to sudden freezes. However, if temperatures are consistently low, plants can acclimate, or “harden,” and become more tolerant of low temperatures. It is hard to predict the extent of the cold temperature damage in cool-season forages. More than just temperature, prolonged exposure can cause greater damage. The maturity stage, fertility level, and plant moisture level all affect the response. The field layout, irrigation, fertilization, and related practices can also influence the outcome.

Cool-season forages grow best at temperatures between ~65° and 75° F. Temperatures below 45° F will stop growth. The critical temperature at which irreversible damage begins depends on the plant growth stage and the exposure duration. The two most sensitive stages are the seedling (before tillering) and the early reproductive phase. During the entire vegetative stage, the growing points (the meristems) are protected below ground, as soil temperatures fluctuate less than air temperatures. However, the new plants (seedlings) are quite tender, and take time to harden, and can get damaged from frosts, or even killed if exposed to prolonged cold (as we saw in 2023). As plants grow and form a closed canopy, they provide insulation for the entire canopy against cold temperatures.

Later, prior to reproduction, the growing point is elevated (jointing), and reproductive structures start forming (bolting and flag leaf stage). Freezes can then injure that elevated growing point. Further along, when the reproductive phase starts (late boot or heading stage, when pollination starts), cold temperatures can kill the antlers, stigmas, or, later, small embryos, and produce “blank” or “bleached” seedheads (Figure 3C). During early reproduction, temperatures below 30° F for more than 2 hours can result in sterile florets. An article written by the University of Nebraska’s cropping systems specialist, Robert Klein, shows the effect of freeze injury in different stages of wheat.

Figure 2. Oat in vegetative stage with growing points below soil surface (A), and in early reproductive stages with gowing points being elevated above soil surface (B). (C) shows a comparison between two plants in vegetative (left) and reproductive (right) stages, with the flag leaf already showing signs of cold injury.

–

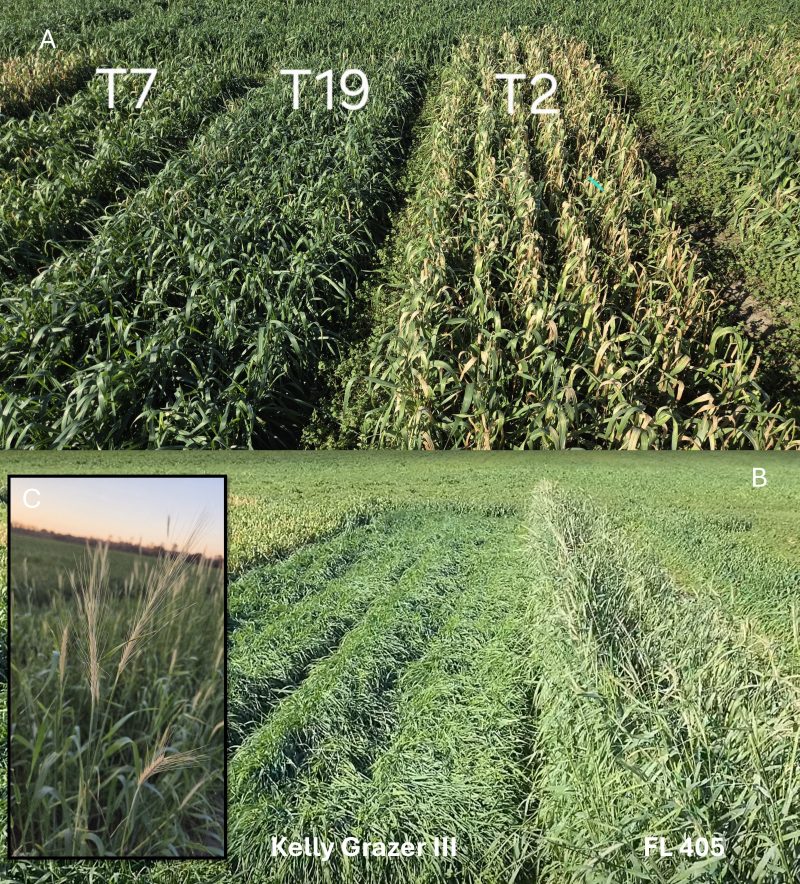

There is a large variation in cold tolerance between species and varieties. In general, rye is more cold-tolerant than triticale and ryegrass, while oats are often the most sensitive, along with wheat. But varieties also matter (Figure 3). On the variety level, growth habit and maturity are most influential. In Florida, we often select early-maturing varieties for early grazing or to cut for silage before corn planting in March. However, early maturity increases the risk of cold damage, as those forages are entering the reproductive stage while frost risk remains high. We can choose materials that are either more cold-tolerant or are early maturing, but not both. To mitigate this issue, producers can mix early maturing species and varieties with those that are more cold-tolerant, acknowledging that canopy growth stages will be uneven. This is not an issue for grazing, where extending the grazing season is desirable, but it can be for silage and hay production.

Figure 3. Triticale with different cold tolerances, where T2 had greater injury from cold than T19 or T7 (A). Differences in maturity in rye, where FL405 is a very early maturing material, and Kelly Grazer III is late (B). The early January frosts resulted in bleached seedheads for FL405 (C).

How to define if the damage was significant?

- At first, plants will be lying down, appearing limp or flaccid, as the cell rupture will compromise plant structure. They will be dark green and mushy. Often, the damage is on the tips and top leaves, but severe cold weather can affect all the canopy.

– - Look for twisted leaves (new or flag leaves are more sensitive), normally showing 2-3 days after the frost.

– - After 2-3 days, leaves will appear chlorotic (yellow-white); next, in around a week, they will die and appear necrotic (brown).

–

Making decisions

- If cold damage is significant, where you see mushy leaves, and the canopy laying down, consider harvesting or grazing shortly after, to avoid greater losses.

– - Especially for dairies that are banking on a single cut, if the damage is extensive, the oats and triticale may not recover in time before the end of February for silage harvest.

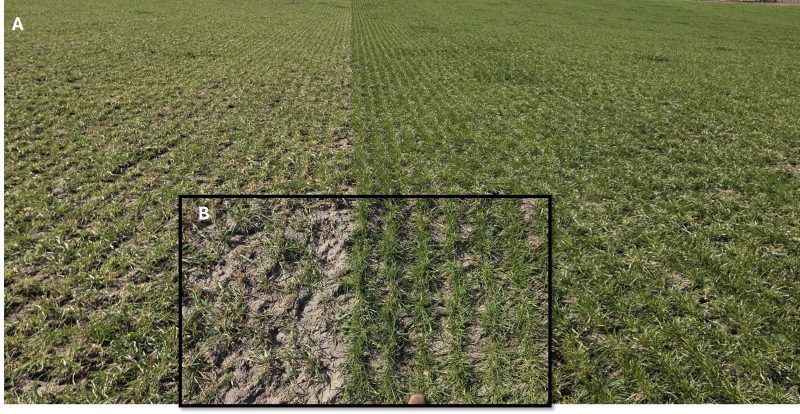

– - In grazing systems, especially if ryegrass is planted together, grazing off the frozen plants will open the canopy for more growth. Do not overgraze; you will expose growing points and limit regrowth (Figure 4). The goal is to remove only the damaged tissue.

– - If small grains are already jointing (elevating the growing point) or bolted (entering reproductive phase), the damage is likely irreversible, and those plants will not grow much more afterwards.

– - Can irrigation help? A soil near field capacity (i.e., moist but not excessively so) is ideal but will not prevent canopy damage. For forages that are still in the vegetative stage, with growing points low (often below ground surface), this might be an effective practice. Moist ground cools off more slowly than drier soil. However, running irrigation just prior to the frost might in fact enhance the potential damage, by creating a humid micro-climate that could hold lower temperatures longer. This strategy differs from frost protection used in many fruit crops, where water is used to keep plants above freezing, and, if temperatures are sufficiently low, ice will form around leaves or fruits and insulate them from further cold. This will not be a feasible strategy for forages, as they require constant irrigation across the area.

– - If pastures have recently been fertilized with nitrogen (< 1 week), there can be an accumulation of nitrates in tissue. If that is the case, hold grazing off. Haying will not reduce nitrates (although ensiling can), but cold-damaged forages can then be diluted with other forage or feed sources.

Figure 4. Overgrazing is detrimental to pasture growth and animal performance. The pasture on the right has a mixture of ryegrass, while the pasture on the left has only small grains. Ryegrass is lower growing and was able to avoid excessive grazing. Note on (B) the amount of exposed ground, meaning less radiation is captured by the plants, which results in slow regrowth. Overgrazing also exposes the growing points, which can be more damaged by the cold weather than a taller, denser canopy.

–

Planning for the future

-

-

Figure 5. Horizon 306 oat is a later-maturing and more cold-tolerant oat. The front half of the plot received limited irrigation, and had more cold damage and susceptibility to diseases (barley yellow dwarf virus) than the back, where water and nutrients were not limited

What can we do to have better pastures for the future, considering such variable weather?

– - Consider using forage mixes. Oats are more sensitive to cold weather, though they are among the highest-yielding and offer high nutritional value. Adding another small grain, such as triticale, and ryegrass can extend the grazing season and provide an additional layer of resilience, given triticale’s disease resistance and cold tolerance. However, this year even triticale (especially the early varieties) have suffered from the cold weather.

– - Manage pastures to establish well and quickly. Lack of nutrients or water will cause plants to grow slowly, with prolonged exposure. Weak plants are more susceptible to stressors, including abiotic (cold) and biotic (insects and diseases). Figure 5 shows the same variety in the same plot, but with limited irrigation in the front half. Where growth was slower, plants sustained greater frost damage and were more prone to barley yellow dwarf virus.

– - Fertilization and irrigation (if available) can help plants get up and going quickly. Once well established, they are more tolerant of stressors.

-

- Cold-Weather Effects on Cool-Season Forages in 2026 - January 30, 2026

- Variety Choice Matters – Results from the 2025 Spring Corn Silage Variety Trial - January 9, 2026

- 2025 Southeastern Hay Contest Sets New Records - October 24, 2025