by Larry Williams | Aug 2, 2018

Paper wasp, Photo Credit: UF/IFAS Extension

I respect the fact that wasps can sting when threatened or disturbed. But I also respect the fact that they are beneficial.

Every time I’ve been stung by wasps, I either accidentally disturbed a nest that I didn’t know was there or I intentionally disturbed the nest and paid the price.

Paper wasps are common in Florida. They frequently construct and attach their paper-like nests to building eaves or the ceilings of porches. The adults seek out caterpillars, which they sting and paralyze. They then take the caterpillars back to their nest and place them in individual cells as food for the developing larvae.

I’ve witnessed the paper wasp as it stings and carries away a caterpillar from my vegetable garden. They are busy insects and are doing us gardeners a favor by reducing the population of caterpillars in our landscapes and gardens.

There are other beneficial wasps in Florida. Mud daubers, for example, build their mud-like nests on the sides of buildings close to human activity.

Mud dauber, Photo Credit: UF/IFAS Extension

The mud dauber is not as aggressive as the paper wasp. It rarely stings people. It stings and paralyzes spiders. The mud dauber lays an egg on each paralyzed spider and seals it inside a chamber in its earthen nest. Upon hatching, the wasp larva feeds on the body of the spider. An emergence hole is made as the young wasp leaves the mud nest.

It may not be wise to tolerate all wasp species living in close proximity to your home. Even though yellow jackets, a type of wasp, could be considered beneficial, they are too aggressive and too likely to repeatedly sting to have as close neighbors. I also would be concerned with any type of wasp or bee nest existing in close proximity to individuals with a known allergy to insect stings.

Just because an insect has the ability to sting, it’s not all bad. Wasps can serve a beneficial purpose. But you’ll have to decide for yourself how close to you they can build their nests. The front porch may be too close.

Posted as part of the “Best Of” series, from August, 2014

by Larry Williams | Apr 16, 2018

Cold injury to lawn. Photo Credit: Larry Williams

Patience, warmer soil temperature and correct lawn management will solve many spring lawn problems.

Many spring dead spots in lawns are caused by something that happened the previous growing season or winter. For example, a late application of a high-nitrogen fertilizer can decrease winter survival. It’s best to not fertilize our lawns after early September.

An insect or disease problem during fall many times goes unseen as the grass is beginning to go dormant. The following spring, as the lawn begins to green up, evidence of a fall pest is clearly visible by brown dead, grass. The pest may not be present or active during spring.

Poor maintenance practices may be to blame for spring dead spots. Over-watering, shallow watering (watering frequently for short periods), mowing too low, too much fertilizer and herbicide injury can result in poor lawn performance come springtime.

Regardless of cause, problem areas within lawns are slow to recover during spring due to frequent cool night temperatures. Frequent cool nights keep the root zone cool.

Cool soil temperature doesn’t allow rapid root regeneration in spring, which inhibits top growth in your lawn. Cool soil also decreases availability of some needed nutrients. For example, poor availability of iron because of cool soil is a common cause for bright yellow areas within lawns, especially in centipedegrass. Cool soil also decreases availability of phosphorus and potassium, which can result in reddish-purple grass blades, intermingled throughout the yard. As soil temperature increases, availability of nutrients improves and the yellow and purple areas turn green.

Have patience with your lawn and follow good maintenance practices this spring. Provide ½ to 1 inch of water when the grass shows signs of wilt. Fertilize and lime based on the results of a reliable soil test. And, mow at a high setting. Good lawn maintenance info is provided at the YourFloridaLawn website.

Consistently warmer nights will allow the soil temperature to warm, which will improve turf root growth, nutrient availability and lawn recovery. During many years in North Florida, it’s well into the month of May before our lawns begin to recover.

If the lawn has not made a comeback by late spring or early summer, it may be time to consider reworking and replanting the dead areas or maybe consider replacing them with something other than grass, if practical.

by Larry Williams | Mar 21, 2018

Tawny mole cricket adult.

Credit: L. Buss, UF/IFAS, IPM-206

The best time to treat for mole crickets is June through July, but don’t treat at all if mole crickets have not been positively found and identified in the affected lawn areas.

Don’t worry about the adults that are seen flying around lights in the evenings or about the mole crickets found dead in swimming pools this time of year. They are in a mating phase and are doing very little to no damage to lawns during late winter and spring.

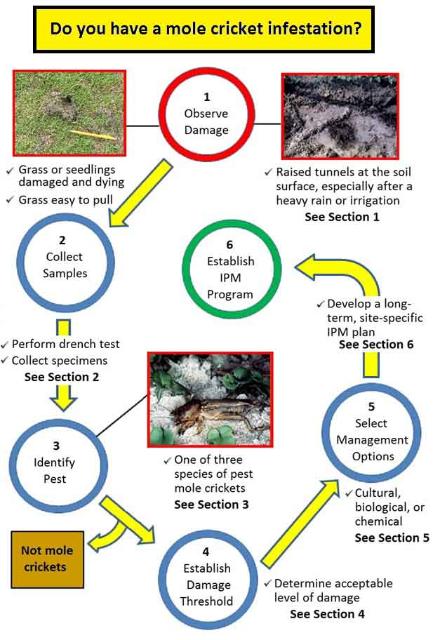

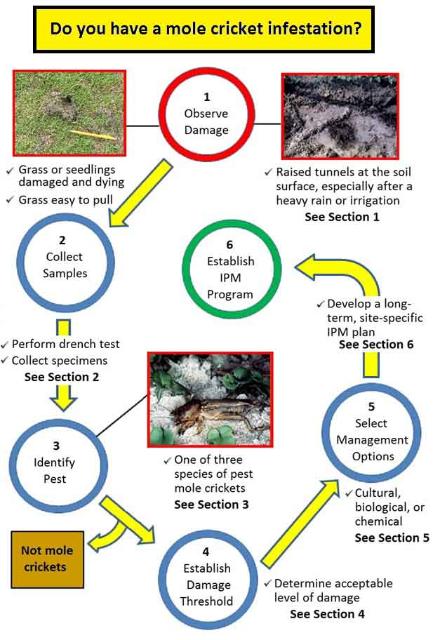

We can take advantage of the fact that there’s only one generation per year in North Florida. The eggs will have all hatched by mid to late June. At that time, you’re dealing with young mole crickets that can’t fly and that are much more susceptible to the insecticides designed to kill them. Mole crickets spend winter as adults in the soil. In late February and March, adults emerge and begin mating. Shortly after mating, males die and females fly to suitable areas for egg laying. Mated females deposit eggs in tunnels. After depositing her eggs the female dies. Attempting to control adult mole crickets during this mating period a waste of time, money and product. Plus, adult mole crickets are difficult to control and can easily fly out of treated areas. See this excellent graphic from the Mole Cricket IPM Guide for Florida.

IPM-206: Mole Cricket IPM Guide for Florida

Figure 1. Pest mole cricket management: observe damage, collect samples, identify specimens, establish a damage threshold, select management options, and develop a long-term IPM program. Graphic sourced from Edis Publication IPM-206: Mole Cricket IPM Guide for Florida

You can easily determine if mole crickets are the cause for your lawn problem by flushing them out with a soap and water mixture.

Mix 1½ ounces of a lemon scented liquid dishwashing soap in two gallons of water in a sprinkling can or bucket. Pour the soapy water over an area approximately four square feet and count the number of mole crickets that emerge. It only takes several minutes for mole crickets to crawl to the surface after the soap treatment if they are present. Repeat the process around the yard where you suspect mole cricket problems. If you flush an average of two to four crickets are flushed out per site, control may be needed.

There are a number of insecticides on the market to control mole crickets. But before using any product, first identify the problem as mole cricket damage by using the soap flush technique. Then choose a lawn insecticide that lists mole crickets on its label. And finally read the label carefully for use directions, application techniques, irrigation requirements and precautions.

For more information on mole crickets, including recommended insecticides and other non-chemical control options, contact the UF/IFAS Extension Office in your County.

by Larry Williams | Feb 26, 2018

Cold injury to lawn caused by early fertilization. Photo credit: Larry Williams

February can be a confusing month for North Florida gardeners. Winter isn’t over. So don’t let spring fever cause you to make some gardening mistakes. Let’s take a look at some dos and don’ts of February gardening.

Despite colder temperatures that we can experience this month, it’s still okay to plant trees and shrubs from containers. The roots are better protected in the ground and will quickly grow outward to establish as compared to being exposed to cold temperatures above ground, confined in a container. But be cautious about planting cold sensitive tropical plants too soon while freezing weather is likely. Bare-root trees and shrubs (those with no soil attached to the roots) should be in the ground promptly. This includes bare-root nut and fruit trees, pine and hardwood tree seedlings and bare-root roses. Dormant season planting allows time for establishment before hot weather arrives.

February is a good time to transplant or move trees and shrubs that are in the wrong place. Consider moving plants that require pruning to force them to “fit” into small or confined spaces. Move them to an appropriate location where they can grow to full size. Then you can plant something new and appropriately sized for replacement.

Late February is a good time to prune overgrown shrubs such as ligustrum and holly. These plants usually respond well to severe pruning and can be pruned almost to the ground, if necessary. But remember, they will eventually regrow to their larger size. Prune to shape and thin broadleaf evergreens and deciduous flowering trees such as oleander, crape myrtle and vitex. Avoid severely pruning narrow leaf evergreens such as junipers because they have few buds on old wood from which to form new growth. Mid-February is a good time to prune bush roses, removing dead or weak canes. Leave several healthy canes and cut these back to about eighteen inches. Delay doing much pruning on early spring-flowering shrubs such as azalea and spirea until shortly after they flower. Pruning these plants now will remove present flower buds before they can open. Prune deciduous fruit trees such as peach, plum, apple, etc.

If your lawn has had a history of problems with summer annual weeds such as crabgrass, apply a pre-emergent herbicide. This should be done February 15 to March 1 when day temperatures reach 65° to 70°F for 4 or 5 consecutive days. A second application may be needed eight weeks later. Many people fertilize their lawns too early. Wait until April to fertilize to prevent lawn injury and for the most efficient use of the fertilizer.

by Larry Williams | Dec 1, 2017

Tulips at the U.S. Botanical Garden in Washington, D.C. Image Credit: IFAS Gardening Solutions

Q. I’ve seen the beautiful tulips of Amsterdam and would like to grow some here in North Florida. So I ordered some tulip bulbs. Can I plant these in North Florida?

A. Tulips are treated as annuals in Florida. We have two problems with tulips this far south. First, they do not receive enough cold weather to meet their requirements to bloom. Secondly, it gets hot quick enough in the spring to cause the foliage to die prematurely, which does not allow the tulip plants enough time to store sugars in the bulb to resume growth the following year. As a result, the bulbs become smaller and weak and flower poorly if at all the following year. At best you may get one to three years’ worth of blooms out of a tulip in our area no matter what you do. Most tulips will only bloom once in our area and then they are spent. Florida doesn’t provide the right kind of weather for tulips. We may have cold weather for a few nights. Then it warms again. This goes on all winter. Tulips need consistently cold weather in order to initiate flower buds.

You can provide an “artificial cold winter” by placing the bulbs in a refrigerator for about 8 weeks prior to planting. This requires purchasing the bulbs ahead of time in order to provide this chilling treatment and still have time to plant during late fall to mid-winter (late November to mid-January). Some nurseries sell pre-chilled bulbs, most don’t. The above treatment will meet their requirements for flowering but does nothing to offset the fact that it gets warm too quickly in the spring for tulips.

The few people that grow tulips in Florida either buy pre-chilled bulbs or place them in the refrigerator, plant them, enjoy their blooms the following spring and then throw them away. They treat them like annuals.