by Mark Tancig | Jan 29, 2026

Most folks are familiar with the concept of supply and demand and how it affects cost. The more numerous a product, the lower the cost. The cost also reflects value, so the more abundant something is, typically the lower the value. This idea of abundance being tied to little value can also be applied to the amazing world of nature around us. Water, for instance, is usually valued little in areas where it is abundant compared to areas where it is scarce. Unfortunately, when it comes to common native plant species found in our local ecosystems, their sheer abundance leads many to consider them not too valuable. However, sometimes, if we step back and learn about these species, we find that many may be locally abundant, but globally very special. Hopefully, this new found knowledge encourages us to value them a little more!

Saw palmetto is common element of many Florida ecosystems. Credit: Gary Knight, Florida Natural Areas Inventory.

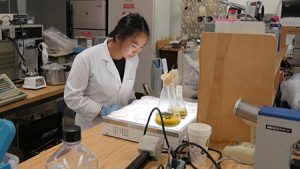

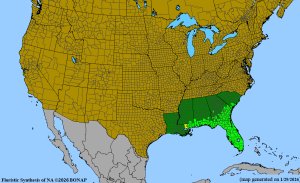

One such example is our very common saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), a plant that is so common in our area that it often goes overlooked and undervalued. How many of you have observed a pine flatwoods loaded with saw palmetto, and gone – “Ehh, it’s so plain and boring?” However, saw palmetto, while locally abundant, is not so plain and boring. Did you know that saw palmetto is found nowhere else on Earth except in our little pocket of the southeastern USA? Its range hugs the Gulf coastal plain from Louisiana to South Carolina, and that’s it.

The limited range of saw palmetto. Credit: Kartesz, J.T. 2026. Floristic Synthesis of North America, Version 1.0. Biota of North America Program (BONAP) [website http://bonap.org/] Chapel Hill, N.C

- Saw palmettos are a native, flowering shrub that do well in ornamental landscapes. They provide a tropical look, and the flowers are very attractive to insects and other pollinators. Just be sure to select the right place for them, as they do expand to 4-10 feet wide so it can become a problem near walkways or in tight spaces.

Saw palmetto does spread wide, so give it plenty of space. Credit: Karen Williams, UF/IFAS.

- While saw palmetto fruits are an important food source for birds and other wildlife, humans also have an interest in them. The fruits are harvested by pharmaceutical companies for medicinal purposes, and extracts of saw palmetto fruits are easily found for sale in health food stores and online. The extracts are mainly marketed as a natural remedy for issues related to enlarged prostate or inflammation, though many physicians and medical groups remain skeptical of any benefits.

The fruits of saw palmetto are valued by wildlife and humans alike. Credit: USDA.

- Saw palmetto clumps can live a long time! As a clonal shrub species (it spreads from runners), it has long been assumed that each clump could be as much as 500 years old. However, recent genetic work has found that saw palmetto clumps living in the Lake Wales Ridge of Florida are at least 1,000 to 5,000 years old, conservatively. This means that there are likely saw palmettos living in south Florida that were around when Aristotle was tutoring Alexander the Great!

Hopefully, you now value saw palmettos just a little bit more than before you started reading this article. Knowing that such a unique plant is right in our backyard, common as dirt, let’s try to find ways to appreciate it and maybe include it in our landscapes, too. Keep in mind that saw palmetto is just one of many locally abundant, but globally special plants that thrive in our local ecosystems.

If you want to start learning more about the plants all around us, you can start by first identifying the species you observe. iNaturalist is a great, free app for your phone that can get you started. Your local extension office is also a resource. Once you have an identification, the Flora of North America and Biota of North America Program websites can give you detailed descriptions and range maps to help you discover the marvelous elements of our local flora.

by Mark Tancig | Dec 18, 2025

Cold hardy citrus are a treat for north Florida gardeners. Credit: Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS

Growing citrus in the backyard is definitely a gardening perk for those living in north Florida. However, our frequent cold snaps are also a source of anxiety for many backyard citrus growers. With weather forecasters excited to highlight dips in temperature, many folks call their local extension office, or head to social media, fretting over what they should do with their citrus. This article is intended to walk you through what to consider when deciding how cold it needs to get before worrying.

First of all, you can really help yourself out by selecting and planting varieties that are known to be cold hardy. In addition to Myer lemon, calamondins, kumquats, grapefruit, and pummelo, other cold hardy citrus varieties include:

- mandarins – satsuma, shiranui, Sugar Belle, Tango and Bingo

- oranges – navel, Hamlin, Minneola Honeybell, and Valencia

Again, the above varieties are known to be hardy, as trees, down to at least temperatures in the mid-20s. Young trees are more susceptible to these temperatures, but once mature, you shouldn’t worry about having to cover them down to the mid-20s. Remember, when covering plants for cold protection, you want the material – whether it be fancy frost cloth or just a simple blanket – to completely cover the tree and drape on the ground. It is the heat leaving the soil that you are trying to capture to keep the tree protected.

When it comes to the fruit, temperatures reaching 26 to 28 degrees for more than two hours may begin to freeze and cause damage. Satsumas, navels, and Meyer lemon fruit have thinner skins compared to grapefruit and so are more likely to freeze. Ripe citrus fruit is more cold-tolerant than unripe fruit due to their sugar content. Unfortunately, if you have unripe fruit, remember that citrus does not ripen off the tree. If you notice frozen fruit after a freeze, salvage any fruit as soon as possible, mostly for juicing, or dispose of in the compost pile.

Citrus fruit showing damage after a freeze. Credit: Mongi Zekri, UF/IFAS

Now, back to the forecasters. They seem to get excited every time we begin to reach anywhere near 32 degrees and begin issuing frost and/or freeze warnings. These are important to consider, but as we now know, just because we’re getting frost or freeze temperatures, it doesn’t mean we’ll lose our citrus. According to the National Weather Service, here’s what all of these advisories mean:

- Frost Advisory – minimum temperature is forecast to be 33 to 36 degrees on clear and calm nights during the growing season

- Freeze Watch – issued when there is a potential for significant, widespread freezing temperatures (32 degrees and below) within the next 24-36 hours.

- Freeze Warning – issued when significant, widespread freezing temperatures (32 degrees and below) are expected.

So, if you hear there is a frost advisory, not much need to worry. If we get all the way to a freeze warning, now we need to pay attention to what the minimum low temperature is forecasted to be. If it’s 28 or below, now we begin to worry about any fruit on the tree. It does have to hold at these low temperatures for several hours before damage occurs, so maybe we’ll be okay. Once we get to the lower 20s, we should probably go ahead pick all of the ripe fruit and hope for the best on any unripe fruit. At these sub-freezing temperatures, we also need to start implementing measures to protect the tree, especially the graft union where the top of the tree has been united with the rootstock, typically indicated by a thickened or swollen like area at the base of the tree. This includes tree covers and soil banking – mounding soil over the graft union through the sub-freezing temperatures.

When covering a tree for cold protection, be sure to drape the cover all the way to the ground. Credit: Jonathan Burns.

Hopefully, this information can help you sleep better during a north Florida cold snap. For more information about citrus and cold damage, there are some great UF/IFAS resources available online. As always, you can also contact your local Extension Office.

by Mark Tancig | Nov 13, 2025

A common site in the garden – multiple hoses pieced together. Be aware of galvanic corrosion! Credit: Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was a nice day in the garden, but when you go to disconnect the hose, it is somehow stuck to the spigot, connector, or other hose. You go and get the pliers, but the hose just doesn’t budge. If this has happened to you, then you now know of the chemical reaction that can occur between aluminum and brass hose fittings. Hopefully, this is just two hoses stuck together, and you can cut them off and replace them with new ends. If the hose is connected to the spigot and won’t budge, you may want to contact a plumber before you create a bigger problem.

While knowing the name of this chemical reaction, galvanic corrosion, doesn’t help you while you curse these hose fittings, it is yet another scientific discovery in the garden. Galvanic corrosion occurs when two dissimilar metals are in electrical contact with each other in the presence of an electrolyte. The metals must be dissimilar in their electrochemical voltage. I know, you just want to disconnect hoses, not learn physics, but this stuff is interesting! Basically, aluminum is pretty reactive, especially when joined up with brass, bronze, copper, and even stainless steel. In the case of our hoses, the water acts as an electrolyte thanks to the calcium present in our delicious and abundant limestone aquifer groundwater. You put all these together and, bazinga, you have the aluminum hose end corroded into your brass hose end so strongly that no pliers will ever unlock them.

This won’t work out well for too long! Aluminum hose end on a brass spigot will lead to galvanic corrosion. Credit: Mark Tancig, UF/IFAS.

So, what do you do to prevent this? The easiest way to prevent galvanic corrosion from ruining your nice day in the garden is to only purchase products with the same material as your spigots. Brass spigots, hose bibs, and hose ends have been the industry standard, while aluminum hose endings seem to be more of a recent occurrence. Aluminum is cheaper, so you can understand why the hose companies would be interested in switching. If you already have two different materials, first check and see if you can get them disconnected. If not, start purchasing new hoses that match the spigot and/or connector. If you can get them disconnected, one method to prevent galvanic corrosion is to just disconnect them regularly to avoid them fusing. Not sure if you’ll remember? You can also use a plastic connector between the hoses to make sure the two metals don’t touch each other or switch out the aluminum hose ends with replacement brass or plastic ends, found at most hardware stores.

A quick fix is to place a plastic connector between the dissimilar metals. Credit: Mark Tancig, UF/IFAS.

Now that you’ve learned about galvanic corrosion, it’s time to get back to gardening. Good luck with those hoses! If you have other gardening questions, please contact your local extension office.

by Mark Tancig | Aug 28, 2025

A healthy coneflower in Leon County’s Demonstration Garden. Credit: Jessica Thrasher

My last Gardening in the Panhandle article was about the many diagnostic services provided by UF/IFAS Extension. In this article, I get to share the results of those services concerning samples recently submitted to the North Florida Education and Research Center (NFREC) Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic (PDC).

Anthracnose in Dogwood (Cornus florida)

Before you get too concerned, this is not the dogwood anthracnose (Discula destructiva) that many of us have heard about from friends and colleagues up north, but one of the more common anthracnose species (Colletotrichum gleosporoides) that infects a variety of fruits, vegetables, and ornamentals.

Typical leaf symptom of common anthracnose disease on a magnolia. Credit: UF/IFAS.

This sample came from a homeowner who brought us a branch from a sick looking dogwood. As many of you know, due to a host of issues, from a short lifespan to living in the southern end of its range in a warming climate, dogwoods have been faring pretty bad lately, with most landscape plantings showing signs of decline or death. While Florida extension agents are informed that it is not the terrible anthracnose from up north, some couldn’t help but think the worst. I was delighted to get a good sample for identifying the disease – one that showed both healthy tissue and diseased tissue – and finally confirm what is causing the common decline symptoms seen in Leon County dogwoods. We bagged up the sample and delivered the next day to the NFREC PDC.

Within a week, the results came back and confirmed the run-of-the-mill anthracnose. This Anthracnose, caused by the fungus Colletotrichum gleosporoides, causes lesions (spots) and/or blights (larger areas of the leaf browning) beginning at the leaf margins that tend to expand and end up causing premature leaf drop. Unfortunately, once we see the damage, typically in the summer, it is too late for any remedy, as the infection begins in the spring. In addition to good practices to encourage good airflow – proper spacing, pruning – and minimize moisture on leaves – irrigate the soil, not the leaves, water in the morning – you will also need to be able to handle some amount of damage. Removing fallen leaves and branches is also helpful to reduce the chance of it cycling back the following spring. Chemical control options include 2-3 applications of preventative fungicide sprays containing chlorothalonil, myclobutanil, mancozeb, or thiophanate methyl early in the spring according to label directions.

Aster Yellows in Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

The deformed blooms of a coneflower with Aster Yellows. Credit: Jessica Thrasher

I’ve had a few questions about Aster Yellows (Candidatus phytoplasma asteris) over the years but have never positively identified the disease in plant material. So, I was somewhat excited to see some of the purple coneflowers in our demonstration garden showing peculiar symptoms. Actually, I was alerted to the strange looking plants by a Master Gardener Volunteer who had been weeding the area. We delivered a sample to the NFREC PDC and in just over a week had results.

Aster Yellows is a disease caused by a phytoplasma and the sample can only be diagnosed with molecular techniques and genetic sequencing. Phytoplasmas, by the way, are a type of bacteria that lack a cell wall and are transmitted plant to plant via insect vectors, typically leafhoppers. Once inside the plant, these phytoplasma can move with plant sap and begin to disrupt the vascular system, causing malformed and discolored flowers, plant deformations, and stunted growth. While members of the Aster family – daisy, sunflower, goldenrod – are common hosts of the disease, Aster Yellows has been found to infect over 300 species in at least 38 plant families. Other species of phytoplasma, also causes lethal yellowing and lethal bronzing of palms and several witch’s-broom diseases.

Since there are not any chemical treatments for Aster Yellows, prevention is key. Once observed, it’s best to remove the infected plants as soon as possible to prevent spreading to other nearby species. In agricultural settings, the leafhopper spreading the bacteria becomes the main target to control using various insecticides. However, in ornamental settings, simply removing the infected plants is the recommended practice.

Stay Observant

Many common diseases are present in every landscape. By ensuring soil and plant health, many of these diseases can be tolerated with little damage. It is important for gardeners and landscapers to be on the lookout for problems so they can be dealt with before they get out of hand. UF/IFAS Extension provides assistance through our county offices and diagnostic clinics to help confirm identification of the pest and provide science-backed control options. If you think you have an issue in your landscape, please reach out to your local county extension office.

Article co-authored by Fanny Iriarte, Diagnostician with NFREC PDC.

by Mark Tancig | May 28, 2025

Extension Agents get used to hearing that the local Extension Office is the community’s best kept secret. As much as we try to let folks know we’re here, many are still unaware of the services we provide. Even amongst the residents that are familiar with us, some of the services available remain unknown, especially our identification and diagnostic services. Here’s a rundown on some of the services available through your UF/IFAS Extension service.

Taking a soil sample. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones

Soil Testing

This is probably our most well-known service, but it’s worth a reminder. For only $3 (pH only) or $10 (pH plus plant macro- and micro-nutrient values) per sample, plus shipping, you can have your soil analyzed in a state-of-the-art facility. To be clear, soil testing only provides a reading of your soil’s chemistry, specifically pH (acidity/alkalinity) and plant nutrient values. It does not provide information on any diseases or potential toxins that may be present in the soil. In addition to the results, you can specify the general type of plant you’re trying to grow (various grass species, vegetables, citrus, general trees and shrubs, etc.) and the report will provide recommendations to adjust the nutrient levels to be sure that plant is able to thrive. Your local agent receives a copy to help answer any questions you may have about the results or recommendations. More about soil and nutrient testing can be found at the Extension Analytical Services Laboratory website.

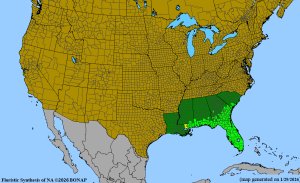

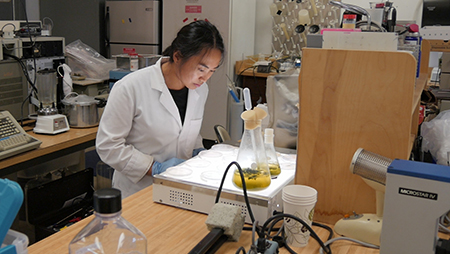

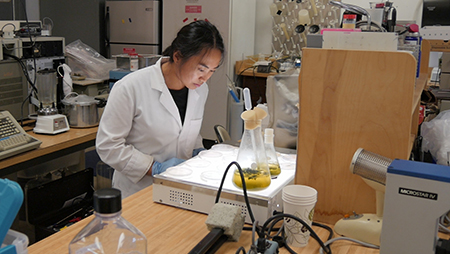

Experts at the Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic can identify diseases present. Credit: UF/IFAS.

Plant Disease Diagnosis

UF/IFAS Extension has a great plant pathology lab on campus, but we also have a great resource close by in Gadsden County at the North Florida Research and Education Center’s (NFREC) Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic. For a modest fee of $30, you can submit a sample of a diseased plant, and the lab manager will use the available methods to confirm the presence of disease and identify the disease-causing organism. Just like with the soil test results, you are provided with a recommendation on how to best treat the disease. The NFREC Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic website has submittal forms, contact information, and directions for collecting a quality sample.

Need help with insect id? The DDIS system can help. Credit: UF/IFAS.

Plant and Insect Identification

While your local extension agent enjoys receiving plant and insect identification, there is an online submittal option available to use as well through our Distance Diagnostic Identification System (DDIS). You can set up an account and then upload photos of plants, insects, mushrooms, even diseased plants, and an expert on UF’s campus will do their best to identify it for you. The DDIS website has more information to help you set up a user account.

The Florida Cooperative Extension Service has many ways to help Florida citizens diagnose their landscape issues using science-based methods conducted by experts in state-of-the-art facilities. The above services are just a selection of the diagnostic capabilities available. To see a complete list, visit the IFAS Diagnostic Services website. You can always contact your local extension office, too, for assistance in identifying plants and insects, as well as diagnosing diseases.