by Mark Tancig | Jun 22, 2017

Recent rains in the panhandle have kept many gardeners indoors. While we’re mostly watching the rain from inside, there are some lawn and landscape tasks to consider.

The most obvious is to turn off any automatic irrigation systems. Although rain shut-off devices are required for all automatic irrigation systems in Florida, many homeowners’ systems are not properly installed, are turned off, or are absent all together. Irrigating during times of adequate rainfall not only wastes a precious natural resource, but it can also be damaging to your turf and landscape plants by creating the perfect conditions for disease, especially fungi.

A rain shut-off device ensures that your irrigation system doesn’t come on during rainy weather. Photo by: Mark Tancig, UF/IFAS.

Something else to consider during all of this rain are potential mosquito breeding sites. Our most irritating mosquito species, those day-biting Asian tiger mosquitoes, love to breed in any small or large, water-holding containers around the house, including birdbaths, plant pot saucers, watering cans, five-gallon buckets, tarps, rain barrels, and the list goes on. The best method of control is to drain these containers every three to five days to prevent mosquito larvae from hatching. Another way to reduce larvae from hatching is to use a Bti product, which come in donut shaped dunks or as crumbles that can be sprinkled in the container. Bti controls mosquito, blackfly, and fungus gnat larvae, but does not harm beneficial insects and animals like birds, bees, butterflies, lizards, and frogs. If mosquitoes from the swamp or wetland behind your lot worry you, remember that those ecosystems have a diversity of insects that prey on mosquito larvae. Those containers in the yard do not have predators and can be a large source of the most aggravating mosquito species. For control of larger areas, including those natural ecosystems, contact your local mosquito control agency for assistance.

Bti bits are a way to prevent mosquito larvae from becoming biting adults. Photo by: Mark Tancig, UF/IFAS.

If you like to play in the rain a little, this is a good time to walk around and observe any runoff issues in the yard (make sure to do this only when it’s safe!). The ideal situation is to have runoff drain away from the house and percolate into landscaped areas. When surveying the yard in the rain, things to look for include areas of standing water (that could be a good location for a rain garden) and areas where erosion may be occurring (consider using berms or plantings to better direct and slow the water). Before doing any major drainage work, always check with your local building department. Some municipalities may require permits to ensure your improvements do not affect your neighbors or others downstream.

Rain gardens can turn a low, soggy spot into an aesthetic addition to your yard. Photo by: Courtney Schoen, TAPP.

If you have any questions about rain shut-off devices, mosquito control, or stormwater runoff, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office for more information. Enjoy the rain; it will be sunny and hot before you know it!

by Mark Tancig | May 25, 2017

One of the main Florida-Friendly Landscaping principles is to plant the right plant in the right place. In Florida, not only does this apply to the zone you’re in, soils you have, and light conditions in your garden, but also ensuring that invasive, exotic plant species are not used. While most of us have heard about invasive, exotic plants – those that invade and disrupt our unique natural habitats – some may not know where or how to find out which plants are, in fact, invasive and exotic. Some of the more famous invasive, exotic plant species, such as kudzu and hydrilla, are familiar to us and we may have an idea of a plant in our garden that is “aggressive”, but how do we know for sure? Since only a handful of the worst invasive, exotic plants are legally prohibited from being sold, how do we know if a plant we are considering purchasing at our local nursery or another plant already in our gardens is an invasive, exotic? A quick internet search for Florida invasive plants gets you various sources of information. How do you choose which to use?

The unique habitats of Florida need our help. Prevent the spread of invasive, exotic species by planting Florida-Friendly plants. Source: Mark Tancig/UF/IFAS.

Fortunately, the researchers at UF/IFAS want you to be able to find the best information in one spot – the UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-Native Plants in Florida’s Natural Areas. This site systematically reviews individual plant species and provides a recommendation as to whether it should be used in North, Central, or South Florida landscapes. Many landscape plants have been reviewed – over 800 – and more are added to the site as reviews are completed. The UF/IFAS Assessment also reviews cultivars of known invasive, exotic plants to ensure that they are sterile and will not revert back to their wild type or hybridize with known invasives, or even closely related native species.

The UF/IFAS Assessment is a simple, convenient source for deciding if a plant should be used in your Florida landscape.

To use the site, simply visit the main web address – assessment.ifas.ufl.edu – and begin typing in your plant name in the search bar. You can begin spelling the scientific or common name and it will start showing possible results as you type. Once you select the plant you’re interested in, it will take you to a new page with photos of the plant, some general information, additional links, and, most importantly, the assessment conclusion for each zone. The conclusion will be one of the following:

- Not considered a problem species at this time,

- Caution, or

- Invasive

Of course, if it’s not a problem, then feel free to use and share that particular plant. If it is a caution plant, then it may be used, but you will want to be extra careful in where you plant it. Those may be better suited as potted plants or planted in areas that are confined, to limit its potential spread. If it’s invasive, don’t plant it.

Caution plants are reassessed every two years while those that are not considered a problem species or are considered invasive are reassessed every ten years.

Another way to use the UF/IFAS Assessment is to filter all reviewed plants by various criteria you’re interested in. If you select assessments on the main page, it will lead you to a list of all reviewed plants. A filter button allows you to choose geographic zone, conclusion type, and growth habit, among some other criteria. This will create a list that can then be exported to a Microsoft Excel table.

As you can see, UF/IFAS is trying to make it easy for you to determine which plants can be used in the landscape without potentially spreading and causing disruption to our unique natural areas.

If you have any questions about individual species that have or have not been assessed, contact your local County Extension Office.

by Mark Tancig | Apr 24, 2017

Source: UF/IFAS.

Impatiens are a very popular annual, bedding plant that provide a nice burst of color in the landscape. The traditional Impatiens (Impatiens walleriana), or touch-me-not, is the one that most gardeners know as needing part shade, but there are also the New Guinea Impatiens (Impatiens hawkeri) that are able to tolerate more sun. In addition to being able to withstand more sunlight, the New Guinea Impatiens also have larger flowers and leaves. Another highlight of the New Guinea impatiens is their increased resistance to downy mildew, a major concern for growers of touch-me-nots, especially in south Florida.

While native to the Old World, Impatiens are not known to invade Florida natural areas but may reproduce by seed. Touch-me-nots are known to spread easily be seed. An interesting fact about Impatiens is their bursting seed pods that can send seeds several feet from the parent plant. This characteristic is what led to the scientific name Impatiens – for impatient – and one of the common names – touch-me-not.

May is a good time to plant Impatiens in north Florida. They prefer slightly acidic soil and should be planted at a 12-18 inch spacing. Impatiens work well as a border planting or in mass plantings. While New Guinea Impatiens tolerate more sun, they still would prefer some afternoon shade. Those growing in full sun will need extra care to ensure they remain well watered. An all-purpose plant food can be applied at monthly intervals for best performance.

Some common varieties of touch-me-nots include ‘Accent’, ‘Blitz’, ‘Carousel’, ‘Dazzler’, ‘Impact’, ‘Impulse’, and ‘Super Elfins’. Common New Guinea Impatiens varieties include ‘Celebration Candy Pink’, ‘Celebration Light Lavender’, ‘Nebulus’, ‘Equinox’, ‘Sunglow’, and ‘Tango’. The newer ‘Sunpatiens’ variety is quite popular and comes in different forms – compact, spreading, and vigorous.

Source: UF/IFAS.

If you have any questions regarding Impatiens, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office or visit our EDIS website at www.edis.ifas.ufl.edu.

by Mark Tancig | Mar 29, 2017

As an extension agent, I’m always curious of what plants folks are using in the landscape. One plant I’ve been noticing more and more of in north Florida, both in containers and in landscape beds, is asparagus fern. Three different plant species go by the name asparagus fern – Sprenger’s fern (Asparagus aethiopicus), foxtail fern (Apsaragus densiflorus), and lace fern (Asparagus setaceus). Property owners should refrain from selecting these plants since they are another example of invasive, exotic species that can spread to natural areas and effect native plant communities.

Native to South Africa, Asparagus species are technically not a fern, but related to lilies, and, yes, asparagus. Its ease of growth has made them a go-to choice for gardeners looking for a hardy, attractive plant. Unfortunately, the red berries that follow the small, white, scented flowers are fed on and spread by birds. The seeds germinate easily and can become established in other parts of the garden or, even worse, a local natural area. The ability of Sprenger’s fern to spread into and disrupt natural ecosystems has earned it a spot on the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council’s List of Invasive Species as a Category I invasive plant. Category I plants are reserved for those plants that have been documented as causing ecological harm to Florida’s ecosystems. Foxtail fern and lace fern should also be used with caution.

Asparagus fern in a storefront planter. Photo Credit: Mark Tancig.

Birds can carry the red berries near and far. Photo Credit: Mark Tancig.

To remove asparagus fern from the landscape, manual or mechanical removal can be effective for small areas. Be careful to dig up all roots. For larger areas, the use of a dilute glyphosate herbicide product will provide control. Retreatment may be necessary.

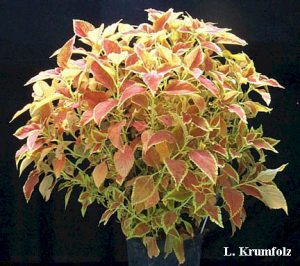

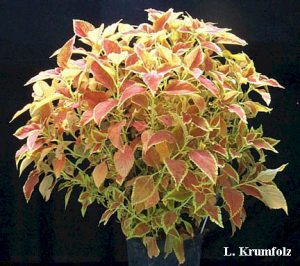

If you’re looking for other alternatives to asparagus fern, try these Florida-Friendly alternatives: Coastal sunflower (Helianthus debilis), coontie (Zamia pumila), Coleus (Plectranthus scutellarioides), or Cast Iron plant (Aspidistra elatior).

Coastal sunflower. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

Coontie. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

Coleus. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

Cast iron plant. Photo Credit: Julie McConnell.

by Mark Tancig | Feb 14, 2017

Daffodil bulbs under trees. Image credit Matthew Orwat

Daffodils are blooming in the UF/IFAS Leon County Extension Demonstration Garden. Daffodils, including paperwhites and narcissus, are in the Amaryllis family and have been cultivated for centuries. The Greeks and Romans admired the beautiful flowers and the plant’s scientific name, Narcissus, is shared with the Greek mythological character who couldn’t stop staring at his reflection. Many old homesites and historical sites in north Florida have daffodil bulbs that have continued to bloom since the early 1900’s. Daffodils can be seen in the winter to early spring and many varieties are hardy in north Florida.

While this is the time for enjoying their flowers, daffodils are planted in the fall. If you’ve caught yourself staring at the beautiful flowers and would like to plant them in your garden, you have time to prepare for next year. Daffodils can be planted once the soil has cooled and do best in sites with mostly sun, but a little shade is okay. Be sure to choose planting areas that don’t collect water. Locations with a slight slope are perfect.

Bulbs can be ordered from catalogs or purchased at local nurseries. Varieties (Division in parenthesis) good for our area include ‘Carlton’ (Large Cupped), ‘February Gold’ (Cyclamineus), ‘Trevithean’ (Jonquilla), ‘Erlicheer’ (Tazetta), and paperwhites (Tazetta).

Once the soil is cool (October to November), bulbs are planted four to six inches deep and should be well watered following planting and, if a dry winter, watered through flowering. Be careful not to overwater, as wet soil promotes rotting of the bulb. After flowering and warmer temperatures, the leaves will begin to fade. Do not remove leaves or flower stalks until completely brown and dry as they provide nutrition to the bulb for storage the next year.

After several years, the bulbs may be divided by digging and lifting the bulbs and separating those that easily break apart from each other. It is best to replant the divided bulbs immediately.

Interesting facts about the daffodil include:

The bulb has the ability to adjust itself in the soil to reach optimal soil depth and temperature.

The term ‘tazetta’ is thought to come from the Italian word for the small cups used for drinking espresso coffee. Next time you stare at the flowers, notice how they resemble a small cup in a saucer.

For more information on growing daffodils in Florida, visit edis.ifas.ufl.edu or contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office.