by Carrie Stevenson | May 27, 2014

Rain gardens can make a beautiful addition to a home landscape. Photo courtesy UF IFAS

Northwest Florida experienced record-setting floods this spring, and many landscapes, roads, and buildings suffered serious damage due to the sheer force of water moving downhill. That being said, we are just entering our summer “rainy season,” so it may be wise to spend extra time thinking about how you want to landscape based on our typically heavy annual rainfall. For example, if you have an area in your yard where water always runs after a storm (even a mild one) and washes out your property, you may want to consider a rain garden for that spot.

Rain gardens work similarly to swales and stormwater retention ponds in that they are designed to temporarily hold rainwater and allow it to soak into the ground. However, they are quite different aesthetically, because they are planted with water-tolerant trees, shrubs, groundcovers and flowers to provide an attractive alternative to the eroding gully that once inhabited the area! Rain gardens are not “created wetlands,” but landscaped beds that can handle both wet and drier soil. Many of the plants best suited for rain gardens are also attractive to wildlife, adding another element of beauty to the landscape.

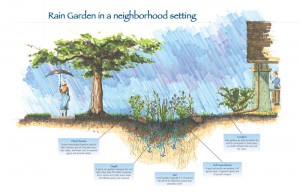

This diagram shows how a rain garden works in a home landscape. Photo courtesy NRCS

A perfect spot for a rain garden might be downhill from a rain gutter, areas notorious for excess water and erosion. To build a rain garden, the rainwater leaving a particular part of the property (or rooftop), is directed into a gently sloping, 4”-8” deep depression in the ground, the back and sides of which are supported by a berm of earth. The rain garden serves as a catch basin for the water and is usually shaped like a semi-circle. The width of the rain garden depends on the slope and particular site conditions in each yard. Within the area, native plants are placed into loose, sandy soil and mulched. Care should be taken to prevent the garden from having a very deep end where water pools, rather allowing water to spread evenly throughout the basin.

Besides reducing a problematic area of the lawn, a rain garden can play an important role in improving water quality. With increasing populations come more pavement, roads, and rooftops, which do almost nothing to absorb or treat stormwater, contributing to the problem. Vegetation and soil do a much better job at handling that water. Excess sediment, which can fill in streams and bays, and chemicals from fertilizers and pesticides are just some of the pollutants treated within a rain garden via the natural growth processes of the plants. Many commercial properties are considering rain gardens, also known as “bioretention” as more attractive alternatives to stormwater retention ponds.

The North Carolina Arboretum used a planted bioretention area to manage stormwater in their parking lot. Photo courtesy Carrie Stevenson

A handful of well-known perennial plants that work great in rain gardens include: Louisiana iris, cinnamon fern, buttonbush, Virginia willow, black-eyed Susan, swamp lily, tulip poplar, oakleaf hydrangea, wax myrtle, Florida azalea, river birch, holly, and Southern magnolia. For a complete list of rain garden plants appropriate for our area, visit the “Rain Garden” section of Tallahassee’s “Think about Personal Pollution” website, tappwater.org or contact your local Extension Office.

by Les Harrison | Dec 2, 2013

Bidens alba is locally know as Spanish Needles because of its stiff prickly structure. It will hitchhike to a new location on anything it contacts.

Hitchhiking was once a common means of low cost transportation. A person would walk to the nearest road and hold out their left fist with the thumb pointed up while attempting to make eye contact with drivers.

In a simpler time hitchhikers were commonly provided a ride to a predetermined spot on the map. In exchange they provided companionship and conversation to the driver.

Change in travel preferences notwithstanding, north Florida still has plenty of active hitchhikers which are seeking a cheap means of travel. The autumn environment stimulates plants with hitchhiking seeds to relocate to new territory open for colonization.

One of the most common hitchhiking seeds locally is Bidens alba. It is known by an assortment of common names including Spanish needles, Beggar’s-tick and Hairy Beggar’s-tick and is a member of the daisy family.

The genus name Bidens means two-toothed and refers to the two projections found at the top of the seed. The species name alba means white which refers to the flowers with white pedals and a yellow center.

This Florida native annual uses the two hooked prongs at the end of the seed to attach itself to anything coming into contact. Each plant produces an average of 1,205 seeds which germinate in the spring.

This weed is common in disturbed areas such as roadside ditches and fence rows with full sun exposure. It is capable of growing to six feet in height, but will take mowing and continue blooming.

The relatively recent interest in wildflowers has encouraged the propagation of this plant for landscaping purposes. Additionally, it is a popular late-season source of pollen for honeybees and other pollinators.

Hackelia virginiana is another hitchhiker currently active in the panhandle. Common names for this weed include Beggar’s Lice, Sticktight and Stickseed and mothers countywide have removed these from their children’s clothing.

The seed pods are approximately 1/8 inch long and are covered with stiff bristly hairs protruding in every direction. Like Spanish needles, anything which brushes against these seeds will carry at least a few to new locations.

The seed pods are green, but will dry to a dark brown. When the outer husk is peeled away, the seed appears as a tiny tan to white bean.

The plant is an erect and has a single stalk about three feet in height. This shallow-rooted plant produces a bloom in mid-to-late summer and seeds in October.

This biennial plant has yet to gain the appreciation of wildflower lovers. It is still considered a weed pest and treated as such.

One byproduct of hitchhiking weeds has been the invention of Velcro. One half of this product resembles coarse fabric and the other side mimics the texture of a cocklebur, a hitchhiking agronomic weed pest.

To learn more about the hitchhiking seeds, visit your local Extension office in person or on the web.

by Julie McConnell | Oct 14, 2013

Swamp Sunflower Photo credit: UF/IFAS Milt Putnam

Fall Blooming Native Wildflowers

Drive along any highway or rural road at this time of year and chances are some color will catch your eye; not so much in the tree tops, but in ditches and right of ways.

Although yellow seems to be the predominant color in the fall, pay attention and you may spot reds, oranges, and even some blues in the wildflower pallet.

Examples of wildflowers that bloom late summer to early fall in the Panhandle:

• Bluestar (Amsonia ciliate), blue flowers, 1-3’

• Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa), orange flowers, 1-3’

• Lanceleaf Coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata), yellow flowers, 1-2’

• Leavenworth’s Coreopsis (Coreopsis leavenworthii), yellow flowers, 1-3’

• Swamp Sunflower (Helianthus angustifolia), yellow flowers, 2-6’

• Rayless Sunflower (Helianthus radula), purple flower, 2-3’

• Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis), red flowers 2-4’

• Lyreleaf Sage (Salvia lyrata), purple flowers, 1-2’

• Goldenrods (Solidago spp.), yellow flowers, 1.5-6’

• Tall Ironweed (Veronia angustifolia), purple flowers, 2-4’

To learn more about these and many other wildflowers read EDIS Publication “Common Native Wildflowers of North Florida.”