by Andrea Albertin | May 4, 2018

Special care needs to be taken with a septic system after a flood or heavy rains. Photo credit: Flooding in Deltona, FL after Hurricane Irma. P. Lynch/FEMA

Approximately 30% of Florida’s population relies on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater. This includes all water from bathrooms and kitchens, and laundry machines.

When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low. In a nutshell, the most important things you can do to maintain your system is to make sure nothing but toilet paper is flushed down toilets, reduce the amount of oils and fats that go down your kitchen sink, and have the system pumped every 3-5 years, depending on the size of your tank and number of people in your household.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

Image credit: wfeiden CC by SA 2.0

How does a traditional septic system work?

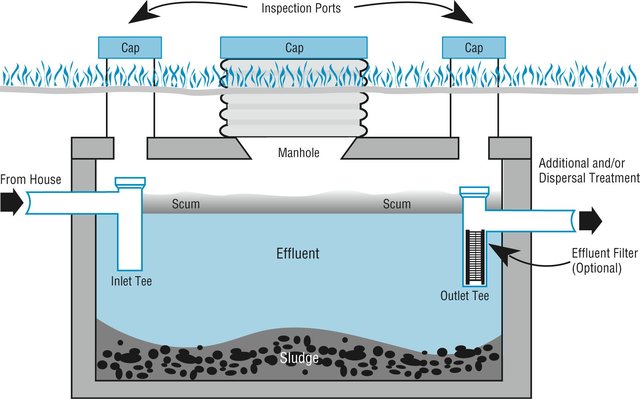

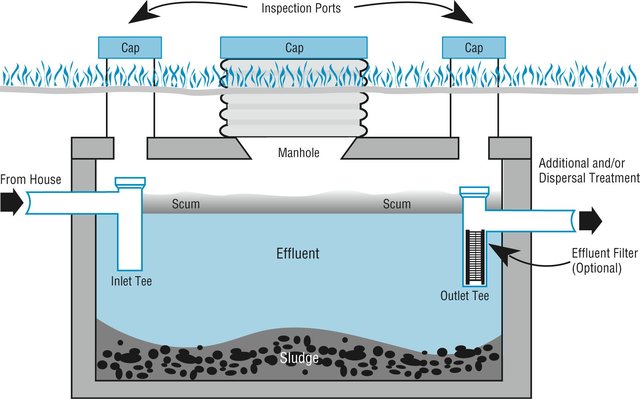

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, made up of (1) a septic tank (above), which is a watertight container buried in the ground and (2) a drain field, or leach field. The effluent (liquid wastewater) from the tank flows into the drain field, which is usually a series of buried perforated pipes. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. Bacteria break down the solids (the organic matter) in the tank. The effluent, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out of the tank and into the drain field where it then percolates down through the ground.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

What should you do after flooding occurs?

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. For your septic system to work properly, water needs to drain freely in the drain field. Under flooded conditions, water can’t drain properly and can back up in your system. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drain field while the soil is water logged. Don’t drive heavy vehicles or equipment over the drain field. By using heavy equipment or working under water-logged conditions, you can compact the soil in your drain field, and water won’t be able to drain properly.

- Don’t open or pump out the septic tank if the soil is still saturated. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened, and can end up in the drain field, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can also cause a tank to pop out of the ground.

- If you suspect your system has been damage, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drain field remains soggy and never fully drains, and/or a foul odor persists around the tank and drain field.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drain field. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain into your septic drain field – this adds an additional source of water that the drain field has to manage.

More information on septic system maintenance after flooding can be found on the EPA website publication https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/septic-systems-what-do-after-flood

By taking special care with your septic system after flooding, you can contribute to the health of your household, community and environment.

by Andrea Albertin | Mar 18, 2018

An estimated 2.5 million Floridians (approximately 12% of the population) rely on private wells for home consumption, which includes water for drinking, cooking, bathing, washing, toilet flushing and other needs. While public water systems are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ensure safe drinking water, private wells are not regulated. Private well users are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water.

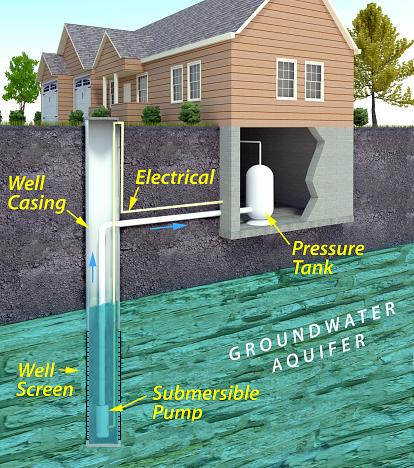

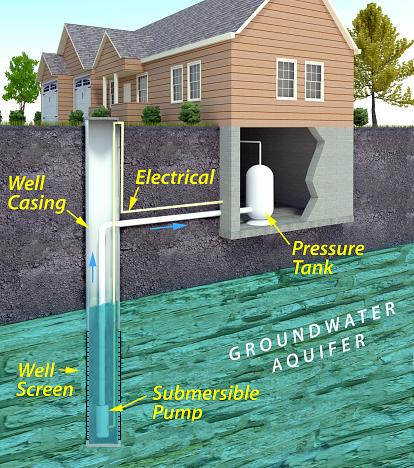

Schematic of a private well typical of many areas in the U.S. Source: usepa.gov

The In Florida, pressure tanks are located above ground since basements are not common. The well casing ensures that water is drawn from the desired ground water source – the bottom of the well where the well screen is placed. The screen keeps sediment from getting into the well, and is usually made of perforated or slotted pipe. The well cap on the surface prevents debris and animals from getting into the well. Submersible pumps (shown here) are set inside the well casing and used for deep wells. Jet pumps are used on the surface and can be used for both shallow and deep wells.

How can well users make sure that their water is safe to drink?

It’s important to have well water tested at a certified laboratory at least once a year for contaminants that can cause health problems. According to the Florida Department of Health (FDOH), the most common contaminants in well water in Florida are bacteria and nitrates.

Bacteria: Labs generally test for Total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically) when a sample is submitted for bacteriological testing. This generally costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

Coliform bacteria are a large group of different kinds of bacteria and most species are harmless and will not make you sick. But, a positive test for total coliforms indicate that bacteria are getting into your well water. Coliforms are used as indicator organisms – if coliform bacteria are in your well, other pathogens (bacteria, viruses or protozoans) that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces. E. coli are one species of fecal coliform bacteria. A positive test for fecal coliform bacteria or E. coli indicate that water has been contaminated by human or animal waste.

If your water sample tests positive for only total coliform bacteria or both total coliform and fecal coliform (or E. coli), the Department of Health recommends that your well be disinfected. This is generally done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your own well can be found

Nitrates: The U.S. EPA set the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for nitrate in drinking water at 10 miligrams per liter of water (mg/L). Values above this are a concern for infants who are less than 6 months old because high nitrate levels can cause a type of “blue baby syndrome” (methemoglobinemia), where nitrate interferes with the capacity of hemoglobin in the blood to carry oxygen. It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that will be drinking well water or when well water will be used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L, never boil nitrate contaminated water as a form of treatment. This will not remove nitrates. Use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply source) until the problem is addressed.

Nitrates in well water come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are is getting into your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, make sure you contact your local health department or a water treatment contractor for more information.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Most county health departments accept samples for water testing. You can also submit samples to a certified commercial lab near you. Contact your county health department for information about what to have your water tested for and how to take and submit the sample.

Contact information for county health departments can be found on this site: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

You can search for laboratories near you certified by FDOH here: https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp This includes county health department labs as well as commercial labs, university labs and others.

You should also have your well water tested at any time when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking your well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well was affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are by no means the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your water and what they recommend you should get the water tested for. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) also maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users: http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html . This site includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 19, 2018

A poultry farm in North Florida used FDACS cost share funds to install solar panels for renewable energy production. Photo source: FDACS Office of Energy

Maximize your farm’s energy savings with FDACS’ free energy evaluations and cost share program

The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) Office of Energy is currently offering free energy evaluations and cost share funds to increase on-farm energy efficiency to agricultural producers in Florida. This includes all types of operations, such as row crop, fruit and vegetable farms, nurseries, livestock and poultry operations, dairies, and aquaculture farms.

What is an energy evaluation and how is it done?

The purpose of the free evaluations (which are valued at $4,500) is to let producers know how they can maximize energy efficiency and ultimately reduce costs on-farm. During these evaluations, members of a Mobile Energy Lab (MEL) walk through the operation with the producer, evaluating all forms of energy use. Since energy use is often linked to water use (irrigation pivots, for example), the team also assesses water use.

MEL teams are made up of energy experts contracted by FDACS from one of three universities: Florida A&M University, the University of Central Florida and the University of Florida. The MEL will be made up of members from the university closest to the farming operation being evaluated.

After the MEL team has finished the on-site visit, it prepares an evaluation and sends it to the producer. The evaluation details energy use and makes recommendations about how to increase efficiency on-farm. These recommendations depend on the operation and what the farmer is interested in doing. They can include switching to more efficient lighting, converting irrigation pumps from diesel to electric, using variable frequency drives (VFDs) on milk vacuum pumps in dairy operations and switching to or adding small-scale renewable energy generation, like solar or biomass, among others.

After a producer decides on changes she or he would like to make, FDACS offers 80% reimbursement (or cost-share) up to $25,000 to implement recommendations made in the evaluation.

An additional advantage of having a free energy evaluation completed by the MEL is that the evaluation can be used to apply for cost share funds from the USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). Producers could potentially receive cost share dollars from both FDACS and NRCS to increase on-farm energy efficiency.

A producer in the Suwanee Valley took advantage of cost share funds to switch from using a diesel irrigation pump (left) to an electric pump (right). Photo source: FDACS Office of Energy

What is the timeframe for applying for energy evaluations and cost share funds?

FDACS offers statewide evaluations and cost share through their FRED Program (Farm Renewable and Efficiency Demonstration). These funds are set to expire September 2018, and so any items or equipment obtained with cost share funds must be purchased and installed by September 2018.

To have enough time to apply for and receive an energy evaluation (which is the first step to obtaining cost share funds), applications for evaluations must be turned in to FDACS by February 1, 2018.

The good news is that a similar program will continue after September. However, it will be in a more geographically restricted area. The Office of Energy received BP RESTORE funds to continue funding energy evaluations and cost share in the Apalachicola and Suwannee River Basins. These funds will be available starting this spring. The office hopes to secure more RESTORE funds in the future to expand the geographic reach of the program.

It’s estimated that dairy farms with 50 cows or more could save 40-55% of milk vacuum pump costs by using a variable frequency drive or variable speed drive (VFD) (shown above) on milk vacuum pumps. Photo source: FDACS Office of Energy

Who is eligible for energy evaluations and cost share funds?

Producers that are eligible for NRCS EQIP funds are eligible for this energy program. As stated by FDACS, this means a producer has to:

- Have control of the land for the term of the proposed contract period.

- Be in compliance with the highly erodible land and wetland conservation provisions described in 7 CFR (Code of Federal Regulations) Part 12.

- Have an interest in the agricultural operation as defined in 7 CFR Part 1400.

- The average adjusted gross income of the individual, joint operation or legal entity, may not exceed $900,000

If you have any questions about these requirements, please contact Takara Waller at the Office of Energy (contact information listed below).

How do you apply for an energy evaluation?

To apply for an energy evaluation, you need to submit an application to the FDACS Office of Energy. Application forms and instructions on how to submit them, as well as more information about the program can be found at http://www.freshfromflorida.com/Business-Services/Energy/Incentives-for-Agriculture-Producers

If you have any questions, Takara Waller from the Office of Energy can help guide you through the process. Her contact information is:

(850) 617-7470 (phone)

(850) 617- 7471 (fax)

Takara.Waller@FreshFromFlorida.com

For more information about NRCS EQIP cost share funds, contact your local NRCS office. Contact information for offices in the panhandle region can be found at https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/fl/contact/local/?cid=nrcs141p2_015022

Your local USDA Farm Services Agency can also provide more information about cost share programs related to energy. Contact information by county is found by selecting (or clicking on) the county of interest on the following map https://offices.sc.egov.usda.gov/locator/app?service=page/CountyMap&state=FL&stateName=Florida&stateCode=12.

Remember: an energy evaluation is the first step in obtaining cost share funds to increase on-farm energy efficiency and savings.

by Andrea Albertin | Jun 3, 2017

The Florida Panhandle received much needed rain this week, helping to alleviate dry conditions in many areas of the region. However, drought conditions persist in the rest of Florida. According to the US Drought Monitor drought conditions range from moderate in north central Florida to dire in the south-central portion of the state. Precipitation is at 25- 50% of normal rates in the Orlando region. In response, city and county governments and Water Management Districts in these areas are increasing restrictions on outdoor residential water use. In homes with irrigation systems, 50% of the water consumed is typically used for irrigation.

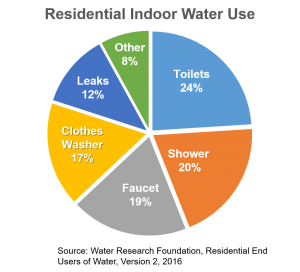

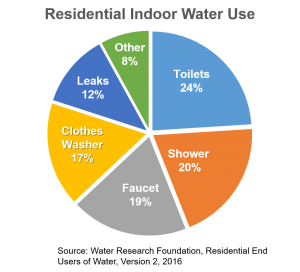

Indoors, we can all greatly reduce water use by adopting relatively simple conservation practices. In a typical household, flushing toilets consumes the most water (24%), followed by showers (20%), faucets (19%), the clothes washer (17%) and leaks (8%) (Source: 2016 report by the Water Research Foundation).

- Consider replacing toilets installed before 1994 with new ones. Pre-1994, toilets used between 3.5 to 7 gallons per flush. From 1994 to date, regulations require toilets to use a maximum of 1.6 gallons per flush and some use as little as 1.28 to 0.8 gallons per flush.

- Placing an object in your toilet tank (like a filled plastic bottle or a brick or two) reduces the amount of water needed to fill the tank and is an inexpensive alternative to replacing a toilet.

- Reduce the amount of time you take per shower, and replace showerheads with low-flow models, which deliver 0.5 – 2.0 gallons per minute. Standard shower heads use 2.5 gallons per minute. Low flow models typically range from $10 to $30.

- Placing a faucet aerator on the end of a faucet can reduce water used from 2.2 gallons/minute to 1.5 gallons per minute. Costs typically range from as low as $5 to $15 each.

- Run the washing machine and dishwasher only when they are full.

- Check for leaks in plumbing and appliances (and fix them!). You can check for toilet leaks by placing food coloring in the tank and seeing if the dye appears in the toilet bowl.

Conserving water at home has the double benefit of reducing your water bill and your energy bill since the amount of energy used to heat water and run the dishwasher and washer/dryer are reduced.

The Southwest Florida Water Management District provides an excellent, easy-to-use online Water Use Calculator, which you can access by going to https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/conservation/thepowerof10/. You can calculate your approximate current water use, and compare that to how many gallons your household could save by changing specific habits (like reducing shower times), reducing outdoor irrigation times and upgrading fixtures and appliances.

The US Drought Monitor can be accessed at http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/Home.aspx

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 29, 2017

One third of homes in Florida rely on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater, which includes wastewater from bathrooms, kitchen sinks and laundry machines. When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low.

A conventional residential septic tank and drain field under construction.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

A general rule of thumb is that with proper care, systems need to be pumped every 3-5 years at a cost of about $300 to $400. Time between pumping does vary though, depending on the size of your household, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce. If systems aren’t maintained they can fail, and repairs or replacing a tank can cost anywhere between $3000 to $10,000. It definitely pays off to maintain your septic system!

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, which is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the ground) and a drain field, or leach field. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. The liquid wastewater, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out through pipes into the drainfield, where it percolates down through the ground.

Although bacteria continually work on breaking down the organic matter in your septic tank, sludge and scum will build up, which is why a system needs to be cleaned out periodically. If not, solids will flow into the drainfield clogging the pipes and sewage can back up into your house. Overloading the system with water also reduces its ability to work properly by not leaving enough time for material to separate out in the tank, and by flooding the system. Sewage can flow to the surface of your lawn and/or back up into your house.

Failed septic systems not only result in soggy lawns and horrible smells, but they contaminate groundwater, private and public supply wells, creeks, rivers and many of our estuaries and coastal areas with excess nutrients, like nitrogen, and harmful pathogens, like E. coli.

It is important to note that even when traditional septic systems are maintained, they are still a source of nitrogen to groundwater; nitrate is not fully removed from the wastewater effluent.

How can you properly care for your septic system?

Here are a some basic tips to keep your system working properly so that you can reduce maintenance costs by avoiding system failure, and so that you can reduce your household’s impact on water pollution in your area.

- Don’t flush trash down the toilet. Only flush regular toilet paper. Toilet paper treated with lotion forms a layer of scum. Wet wipes are not flushable, although many brands are labelled as such. They wreak havoc on septic systems! Avoid flushing cigarette butts, paper towels and facial tissues, which can take longer to break down than toilet paper.

- Think at the sink. Avoid pouring oil and fat down the kitchen drain. Avoid excessive use of harsh cleaning products and detergents, which can affect the microbes in your septic tank (regular weekly or so cleaning is fine). Prescription drugs and antibiotics should never be flushed down the toilet.

- Limit your use of the garbage disposal. Disposals add organic matter to your septic system, which results in the need for more frequent pumping. Composting is a great way to dispose of your fruit and vegetable scraps instead.

- Take care at the surface of yourtank and drainfield. To work well, a septic system should be surrounded by non-compacted soil. Don’t drive vehicles or heavy equipment over the system. Avoid planting trees or shrubs with deep roots that could disrupt the system or plug pipes. It is a good idea to grow grass over the drainfield to stabilize soil and absorb liquid and nutrients.

- Conserve water. You can reduce the amount of water pumped into your septic tank by reducing the amount you and your family use. Water conservation practices include repairing leaky faucets, toilets and pipes, installing low cost, low-flow showerheads and faucet aerators, and only running the washing machine and dishwasher when full. In the US, most of the household water used is to flush toilets (about 27%). Placing filled water bottles in the toilet tank is an inexpensive way to reduce the amount of water used per flush.

- Have your septic system pumped by a certified professional. The general rule of thumb is every 3-5 years, but it will depend on household size, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce.

By following these guidelines, you can contribute to the health of your family, community and environment, as well as avoid costly repairs and septic system replacements.

You can find excellent information on septic systems a the US EPA website: https://www.epa.gov/septic. The Florida Department of Health website provides permiting information for Florida and a list of certified maintenance entities by county: http://www.floridahealth.gov/Environmental-Health/onsite-sewage/index.html.

The Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) identified septic systems as the major source of nitrate in Wakulla Springs, located in Wakulla County. Excess nitrate is thought to promote algal growth, leading to the degradation of the biological community in the spring.

Photo: Andrea Albertin