by Dana Stephens | Aug 2, 2024

Do you know what is your watershed?

There was, is, and will be the same amount of water on planet Earth. Water is a finite resource. The United States Geologic Survey estimates Earth holds around 1,386,000,000 cubic kilometers of water. Only 330,520 cubic kilometers, less than 1% of all water on Earth, is freshwater. This freshwater is available in the soils, atmosphere, biosphere and used by humans.

We all have different connections with water. Maybe it is swimming. Maybe it is enjoyment of clean laundry. Maybe it is the iconic scenes in the 1992 Academy Award for Best Cinematography, A River Runs Through It. Yet, we all depend on water for life. How and why water moves across a landscape to sustain life is important to us all.

Watersheds in the Continental United States (usgs.gov)

Water located on land is called surface water. Water located underground is called groundwater. A watershed is the area of land where surface water and groundwater drain to a common place. Watersheds vary in size from as small as the size of your foot to as large as the watersheds spanning the continental United States. Larger watersheds are composed of smaller watersheds linked together.

Water gradually flows from higher to lower points in a watershed. Precipitation (i.e., snow, rain and everything in between) collects and moves within the drainage area in the watershed. Not all precipitation falling on a watershed flows out of the watershed. Precipitation soaks into the soil and through porous rock moving to lower points in the watershed, returning to and replenishing water stored underground. This groundwater can return to the surface of the watershed via springs or artesian wells, if the groundwater is under enough pressure.

Water can be removed before flowing out of the watershed as well. Precipitation returns to the atmosphere through evaporation as part of the hydrologic cycle. Plants facilitate evaporation to the atmosphere through transpiration where the roots of plants absorb water from the soil and the water evaporates into the air through the leaves of the plants. Human uses of water also impact how water moves through a watershed. Drinking water supplies, industrial operations, or building dams changes the movement of water through the watershed.

Each of us lives in a watershed. There is much benefit to have healthy watersheds. Healthy watersheds are essential to support ecosystems and the services provided, such as safe drinking water, outdoor recreation, economics, and overall quality of life. There are many metrics and assessments used to measure the health of a watershed. Do you know what is the health of your watershed?

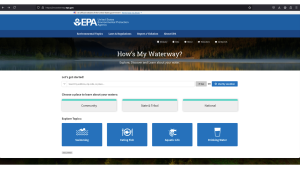

United States Environmental Protection Agency’s How’s My Watershed interactive tool (http://mywaterway.epa.gov)

The United States Environmental Protection Agency developed “How’s My Waterway” to provide the public with information about the condition of their local waters. How’s My Waterway offers three ways to explore your watershed. At the community level, you can see your watershed with details like the water quality, recreation, fish consumption, impairments, and associated plans working to remove impairments. At the state and national levels, you can find information about states/national water program(s) and specific water assessment(s) that affect your watershed.

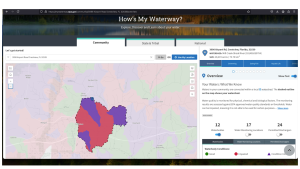

Example–watershed for Okaloosa County UF/IFAS Extension North office.

Let’s give it a try! Go to www.mywaterway.epa.gov in your web browser. Enter the desired address and select >>Go. On the left, you’ll see an interactive map outlining your watershed and the drainage basin(s) that make up the watershed. On the right, there are 10 different tabs allowing you to explore various metrics of the watershed. For example, there is a general tab reviewing the water conditions and states (i.e., good, impaired, or condition unknown) for all surface waters in the watershed. Using the arrow on the right, you can expand each water source to learn specifics about the data-determined state of the water.

Enjoy exploring your watershed! If you have questions about the interactive “How’s My Waterway,” wish to join an educational session to learn more, and/or desire accompanying curriculum, please email Dana Stephens at dlbigham@ufl.edu.

by Thomas Derbes II | May 10, 2024

The Panhandle of Florida is home to many estuaries along the coast, from the Escambia Bay System in the west to the Apalachicola Bay System in the east. These estuaries are very important and are the intersection where rivers (fed from their respective watersheds) meet the Gulf of Mexico and contain many different organisms that help filter the waters before they reach the Gulf. These organisms include oysters, marsh plants, seagrasses, scallops, tunicates, and other invertebrates. In this two-part article, we will explore marsh plants, seagrasses, oysters, and scallops.

Marsh Plants

Marsh Plants is a broad term for a family of grasses that lines the shore and contain grasses like Smooth Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), Saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), and Gulf Cordgrass (Spartina spartinae). These plants help trap sediments before they enter the estuary and are excellent at erosion prevention. When the water encounters the plants, it slows the flow, and this allows for sediments to collect. Marsh Plants are a great tool for shoreline restoration and are a major part of the Living Shorelines Program. The roots of the plants are also very efficient at removing nutrient pollutants like excess nitrogen and phosphorus which are major influencers in eutrophication. Marsh Plants also absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and have been tabbed as “superstars of CO2 capture and storage.” (CO2 and Marsh Plants)

Marsh Grass and Oyster Reef in Apalachicola, Florida – Thomas Derbes II

Seagrasses

Seagrasses are different than Marsh Grasses (seagrasses are ALWAYS submerged underwater), but they offer some of the same ecological services as Marsh Grasses. The term seagrasses include Turtle Grass (Thalassia testudinum), Shoal Grass (Halodule wrightii), Widgeon Grass (Ruppia maritima), and Manatee Grass (Syringodium filiforme) to name a few. Seagrasses help maintain water clarity by trapping suspended sediments and particles with their leaves and uptake excess nutrients in their roots. Seagrasses are very efficient at capturing carbon, capturing it at rates up to 35 times faster than tropical rainforests. (Carbon Capture and Seagrasses) They also provide habitat for crustaceans, fish, and shellfish (which can filter the water too) and food for other organisms like turtles and manatees.

Grassbeds are also full of life, albeit small creatures.

Photo: Virginia Sea Grant

Oysters

Crassostrea virginica (or as we know them, the Eastern oyster) is a native species of oyster that is commonly found along the eastern coast of the USA, from the upper New England states all the way to the southernmost tip of Texas. Eastern oysters are prolific filter feeders and can filter between 30-50 gallons of water per day. As filter feeders, they trap nutrients like plankton and algae from the environment. In areas of high eutrophication, oysters can be very beneficial in clearing the waters by trapping and consuming the excess nutrients and sediments and depositing them on the bottom as pseudo-feces. With oyster farms popping up all over the Gulf Coast, the filtering potential of estuaries is on the rise. (Between the Hinge)

Oysters, The Powerful Filterers of the Estuary – Thomas Derbes II

Scallops

Bay Scallops (Agropecten irradians) were common along the whole Florida Gulf Coast, but their numbers have taken a recent decline and can only be found in abundance in the estuaries to the east of St. Andrews Bay in Panama City, Florida. Scallops make their home in seagrass beds and are filter feeders. While scallops do not contain the filtering potential of an oyster (scallops filter 3 gallons of water per day as an adult), they are still a key part of filtering the estuary. Just like oysters, scallops feed off of the suspended particles and plankton in the water column and deposit them as pseudo-feces on the bottom. The pseudo-feces also help provide nutrients to the seagrasses below.

Bay Scallop.

Photo: FWC

I hope you enjoyed this first article on filterers in the estuary system. While oysters are known as the filterers of the estuary, I hope this has opened your eyes to the many different filterers that call our estuary home. Stay tuned for Part 2!

by Dana Stephens | May 3, 2024

Understanding Salinity in Northwest Florida’s Waters with a Family Activity

Dana Stephens, 4-H Agent

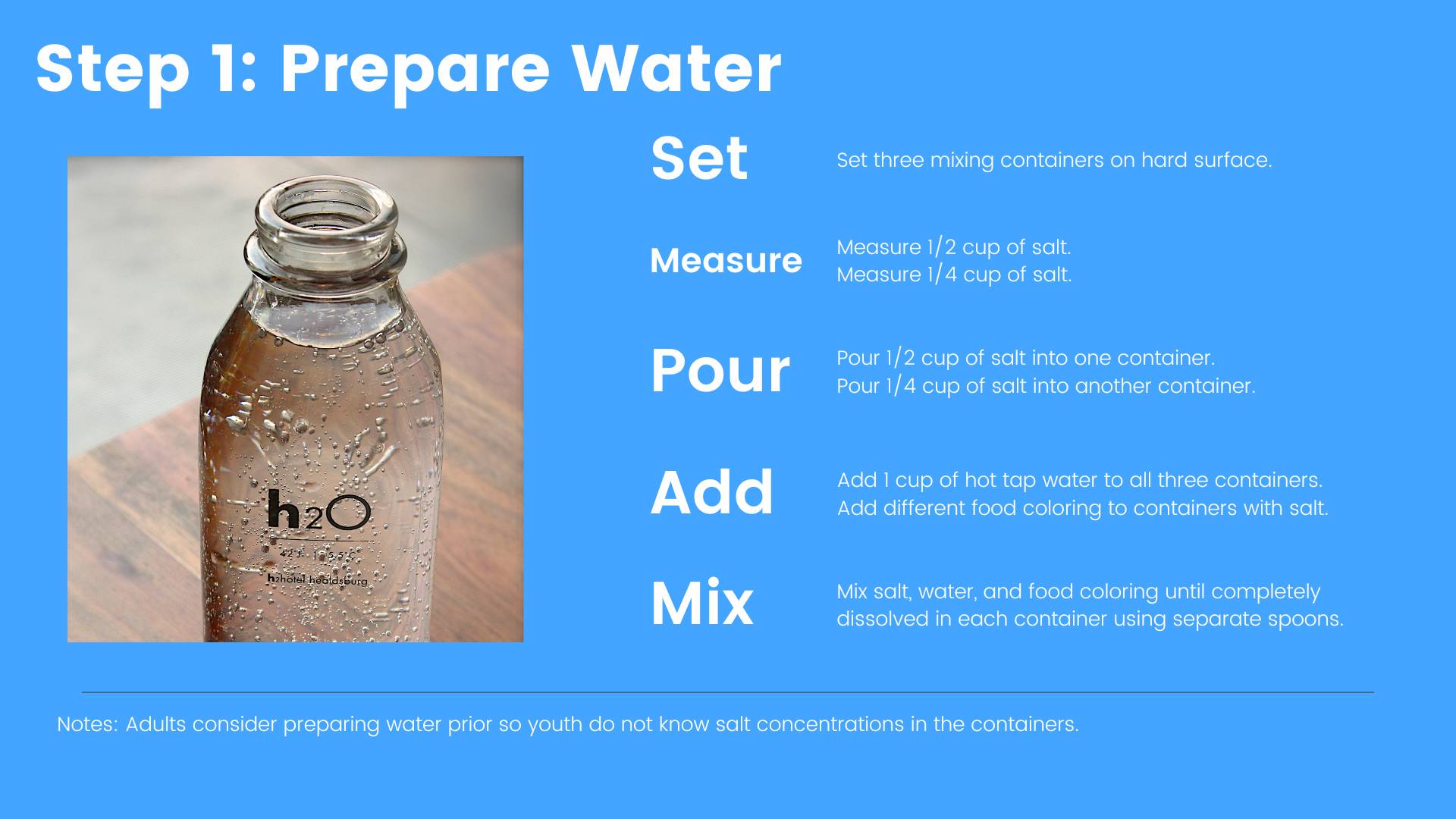

Salinity is the amount of total dissolved salts in water. This includes all salts not just sodium chloride, or table salt. Salinity is important in aquatic environments as many flora and fauna depend on salt and the level of dissolved salts in the water for survival. People interested in the composition of water frequently measure chemical and physical components of water. Salinity is one of the vital chemical components measured and often measured by a device determining how readily electrical conductance passes between two metal plates or electrodes. These units of electrical conductance, the estimate of total dissolved salts in water, is described in units of measurement of parts per thousand (PPT).

At the large scale, Earth processes, such as weathering of rocks, evaporation of ocean waters, and ice formation in the ocean, add salt to the aquatic environment. Earth processes, such as freshwater input from rivers, rain and snow precipitation, and ice melting, decrease the concentration of salt in the aquatic environment. Anthropogenic (human-induced) activities, such as urbanization or atmospheric deposition, can also contribute to changes in salinity.

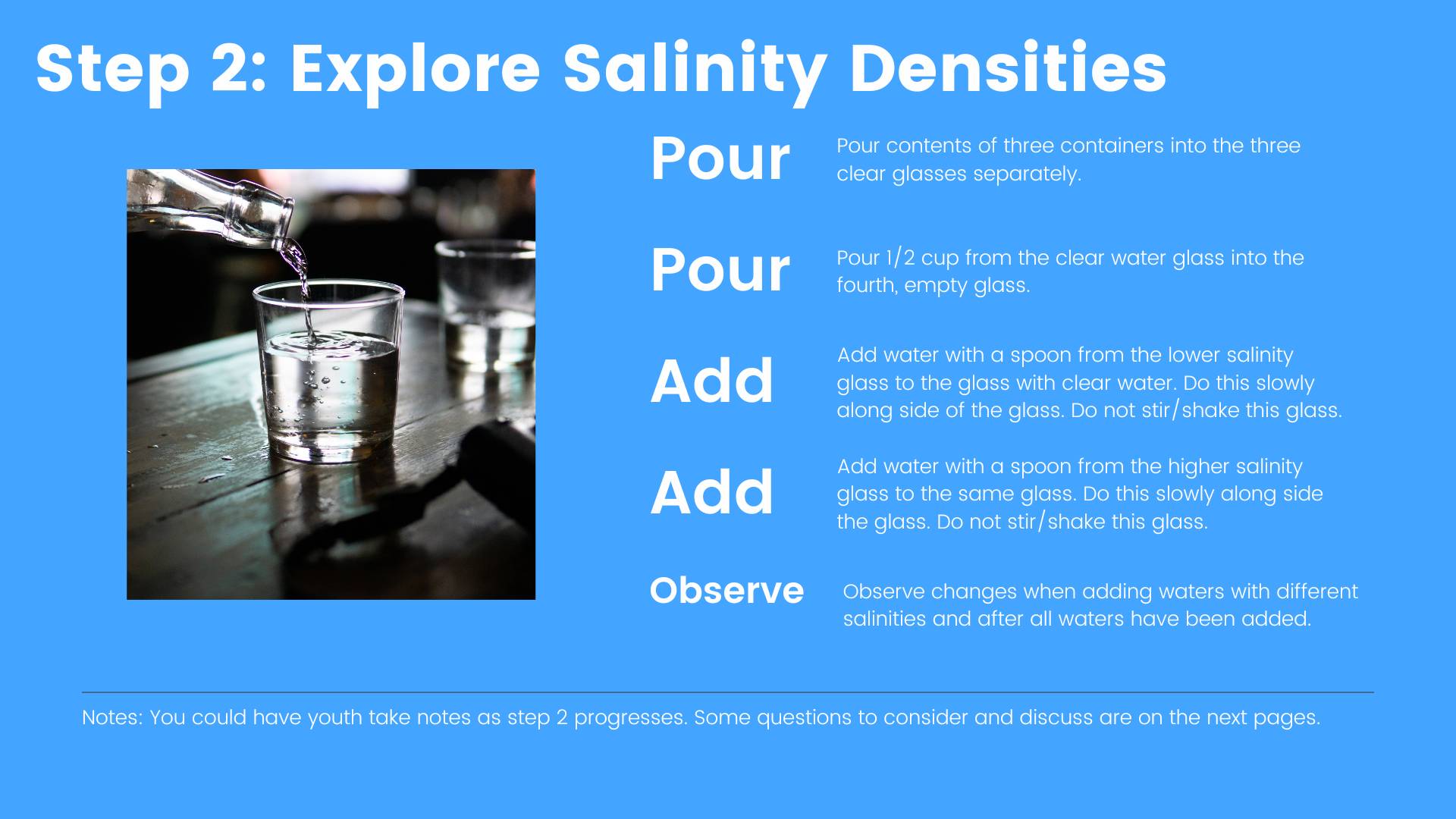

Salinity and changes in salinity affect how water moves on Earth due to contrasts in the density of water. Water containing no dissolved salts is less dense than water containing dissolved salts. Density is weight per volume, so water with no dissolved salts (less dense) will float on top of water with dissolved salts (denser). This is why swimming in the ocean may feel easier than swimming in a lake because the denser water provides increased buoyancy.

Northwest Florida is a unique place because we have a variety of surface waters that range in salinity. There are ponds, lakes, streams, rivers, and springs, which have no to low salinity levels (0 to 0.5 PPT), and commonly referred to as freshwater systems. We house six estuaries—Perdido Bay, Pensacola/Escambia Bay, Choctawhatchee Bay, St. Andrews Bay, St. Joseph Bay, and Apalachicola Bay. Estuaries are bodies of water with freshwater input(s) (e.g., rivers) and a permanent opening to the ocean (e.g., Destin Pass in the Choctawhatchee Bay). Estuarine waters are termed brackish water (0.5 to 30 PPT) due to the dynamic changes in salinity at spatial and temporal scales. Waterbodies with an even more dynamic change in salinity are the coastal dune lakes Northwest Florida’s Walton and Bay Counties. Coastal dune lakes are waterbodies perched on sand dunes that intermittently open and close to the Gulf of Mexico. Sometimes these waterbodies are fresh and sometimes they have the same salinity as the Gulf of Mexico, like after a large storm event. Finally, the Gulf of Mexico, or ocean, has the highest salinity (> 30 PPT) among the waterbodies of Northwest Florida.

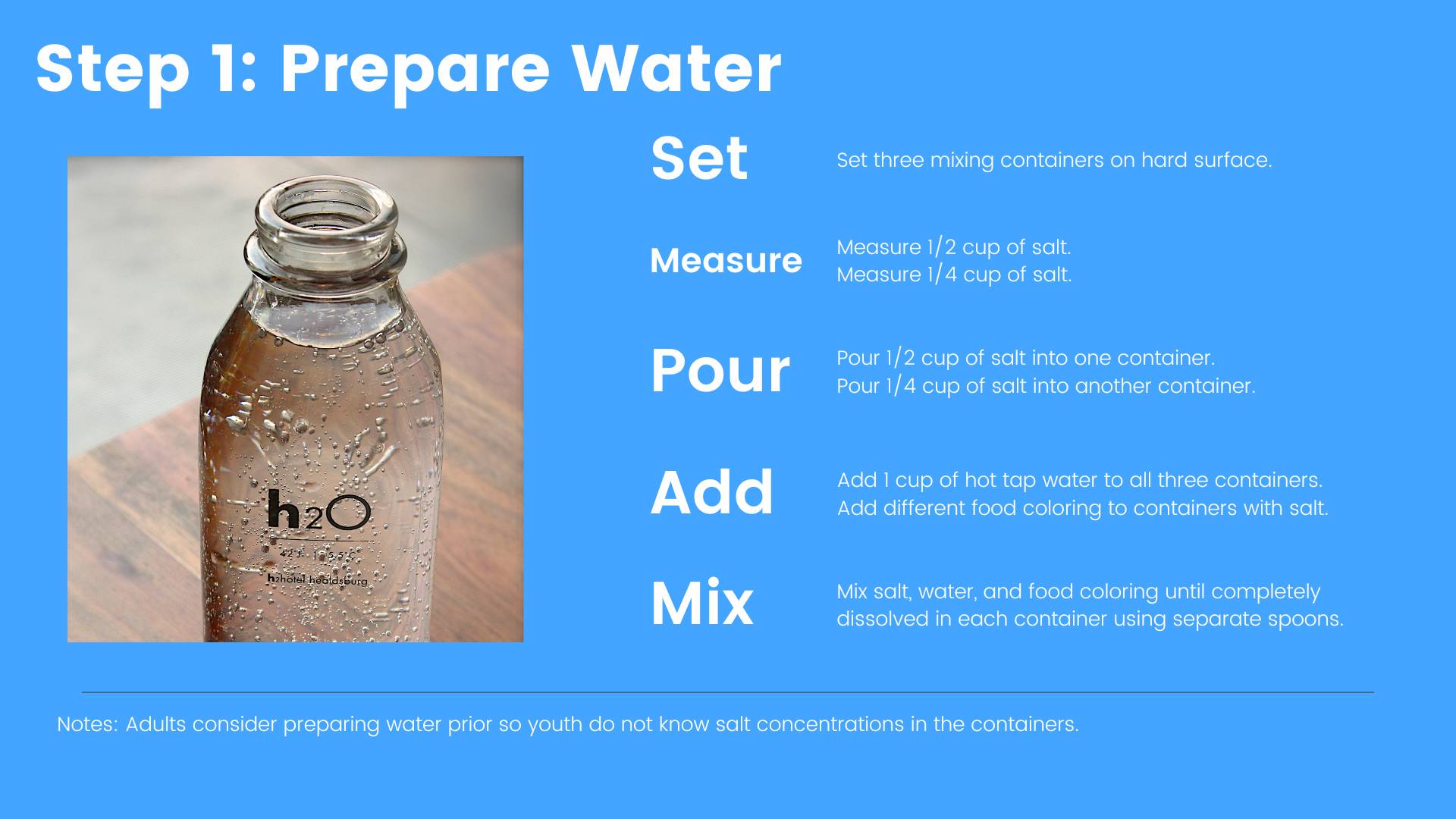

Here is an educational activity for the family to explore salinity and how salinity differs among Northwest Florida waters.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 8, 2021

Well-maintained stormwater ponds can become attractive amenities that also improve water quality. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Prior to joining UF IFAS Extension, I spent three years as a compliance and enforcement field inspector with the local Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) office. It was a crash course in drinking water regulation, wetlands ecology, stormwater engineering, and human psychology. For about half of that time, I worked in the stormwater section with an engineer, certifying the proper construction and specifications of stormwater treatment ponds built for residential and commercial developments. During a construction boom in 2000-2003, my coworkers and I traversed back roads from Perdido Key to Freeport, trying to catch every new project and make sure it was done right. If they weren’t, it also fell to the 3 of us to make sure mistakes were corrected.

Since 1982, Florida Statutes have required that rainfall landing on newly constructed impervious surfaces (rooftops, streets, parking lots, etc.) must be treated before turning into runoff that leaves the property and ends up in local water bodies. The pollutants in stormwater runoff—heavy metals, fertilizer, pesticides, trash, bacteria, and sediment—are the biggest sources of water quality problems for the state, more so even than industrial and agricultural sources.

The most common stormwater ponds have sandy bottoms, grassed berms, and piped inlets with riprap to slow the influx of water. Photo credit, Michelle Diller

Therefore, new developments are required to treat that runoff. This may be accomplished by several means, including regional stormwater ponds. However, the most common are still curbs and gutters, which drain to an often-rectangular hole in the ground with a chain-link fence around it. Ideally, water pools into these dry ponds while raining, reducing flood risk and holding water long enough to allow it to soak into the soil. Most of the ponds in northwest Florida have sandy bottoms that percolate easily. Maintenance is required, however, and when heavier soils, trash, or muck accumulate they must be cleaned out to function properly. Depending on the geology of any given location, the ponds may need sand filters or “chimneys” added to allow water to soak into the native soil.

Admiral Mason Park, adjacent to the Veterans’ Memorial Park along Pensacola Bay, is an example of a regional City stormwater treatment facility that also serves as a park. Photo credit: Visit Pensacola

If an area is naturally low-lying, close to the water table, or has highly organic, water-holding soils, it may be necessary to construct a “wet” stormwater pond. In these, water stands to a level below an overflow device, and can become a water feature for the development. Many residential developers will sell lots around a stormwater pond as “waterfront property” and a well-maintained one really can be a nice amenity. However, at their core, these are stormwater treatment mechanisms. A wet pond functions differently than a dry one and is dependent on healthy stands of shoreline vegetation to take up extra nutrients, metabolize them, and render them into harmless compounds. Many of these ponds have fountains to aerate the water and keep them from becoming stagnant. The City of Pensacola and Escambia County have several great examples of these types of ponds that serve as regional stormwater detention and community amenities. These were constructed in lower-lying areas to handle chronic problems with stormwater in areas that were built up and paved many decades before stormwater rules came into effect. Many other innovative and newer stormwater treatments exist as well, including bioretention, rainwater harvesting, green roofs, and pervious pavement.

by Shep Eubanks | Sep 13, 2019

Common Salvinia Covering Farm pond in Gadsden County

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS Gadsden County Extension

Close up of common Salvinia

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS Gadsden County Extension

Aquatic weed problems are common in the panhandle of Florida. Common Salvinia (Salvinia minima) is a persistent invasive weed problem found in many ponds in Gadsden County. There are ten species of salvinia in the tropical Americas but none are native to Florida. They are actually floating ferns that measure about 3/4 inch in length. Typically it is found in still waters that contain high organic matter. It can be found free-floating or in the mud. The leaves are round to somewhat broadly elliptic, (0.4–1 in long), with the upper surface having 4-pronged hairs and the lower surface is hairy. It commonly occurs in freshwater ponds and swamps from the peninsula to the central panhandle of Florida.

Reproduction is by spores, or fragmentation of plants, and it can proliferate rapidly allowing it to be an aggressive invasive species. When these colonies cover the surface of a pond as pictured above they need to be controlled as the risk of oxygen depletion and fish kill is a possibility. If the pond is heavily infested with weeds, it may be possible (depending on the herbicide chosen) to treat the pond in sections and let each section decompose for about two weeks before treating another section. Aeration, particularly at night, for several days after treatment may help control the oxygen depletion.

Control measures include raking or seining, but remember that fragmentation propagates the plant. Grass carp will consume salvinia but are usually not effective for total control. Chemical control measures include :carfentrazone, diquat, fluridone, flumioxazin, glyphosate, imazamox, and penoxsulam.

For more information reference these IFAS publications:

Efficacy of Herbicide Active ingredients Against Aquatic Weeds

Common salvinia

For help with controlling Common salvinia consult with your local Extension Agent for weed control recommendations, as needed.

by Laura Tiu | Sep 23, 2016

Rocky Bayou Aquatic Preserve – Choctawhatchee Bay, Niceville, Florida – Photo by Laura Tiu

September 17-24, 2016 was the nation’s 28th time to celebrate America’s coasts and estuaries during National Estuaries Week. This week helps us to remember to appreciate the challenges these coastal ecosystems face, along with their beauty and utility.

Estuaries, semi-enclosed bodies of water with both fresh and saltwater, dot the Gulf Coast of the United States from Brownsville Texas to Key West, Florida. These estuaries are important as they serve as drainage basins for many of the large river systems, and play a significant role in the nation’s seafood industry.

Florida’s six major Panhandle estuaries, which includes Perdido Bay, Pensacola Bay (including Escambia Bay), Choctawhatchee Bay, St. Andrew Bay, St. Joseph Bay and Apalachicola Bay, are unique ecosystems teeming with life and diversity. Critical habitat includes important seagrass beds that support both the larval and adult stages of fish and invertebrates. In Choctawhatchee Bay, there is also critical foraging habitat for the federally protected Gulf sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi) and stream habitat for the endangered Okaloosa darter.

Choctawhatchee Bay is in Okaloosa and Walton counties in the Florida Panhandle. It is approximately 30 miles long and from three and a half to six miles wide, with a total area of 129 square miles. It is relatively shallow varying from 10 to 40 feet deep. Large portions of the western half of Choctawhatchee Bay are militarily restricted (Eglin Airforce Base). The Bay is fed by the Choctawhatchee River and numerous small creeks that feed into several bayous. The only opening to the Gulf of Mexico is the East Pass, which ironically is at the Western end of the Bay in Destin, Florida. This is where the saltwater and freshwater mix.

Continued industrial and residential development in the watershed regions that drain into many of these estuaries has impacted them in a number of ways. Pollution comes from storm water runoff, lawns, industry and farms. The shorelines are impacted by development, which causes sedimentation and in turn loss of vegetation. This reduces water clarity and habitat for wildlife.

Many organizations work to protect this estuary and reach out to others through education, restoration, and recreation events. Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance (CBA) is one such organization committed to ensuring sustainable utilization of the Choctawhatchee River and Bay. They, working with their partners, provide leadership for the stewardship of the Bay. Alison McDowell, director of the CBA, notes that 75-85% of commercially and recreationally important species that are caught in the Gulf spend part of their lifecycle in the Bay. McDowell says a key factor in the Bay’s health is monitoring the water quality and reducing erosion, and the Oyster Reef Restoration program started in 2006 does just that.

There are often opportunities for the general public to join in some of the conservation efforts taking place in the Bay. For more information, like the Okaloosa or Walton County Extension Facebook page.

Kayaking Choctawhatchee Bay – Photo by Laura Tiu