by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 23, 2018

Local estuaries are a beautiful place to explore with your family. Credit: Matthew Deitch, UF IFAS Extension

Florida’s rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries are central features to the identity of northwest Florida. They provide a wide range of services that benefit peoples’ health and well-being in our region. They create recreational opportunities for swimmers, canoers, and kayakers; support diverse wildlife for birders and plant enthusiasts; sustain a vibrant commercial and recreational fishery and shellfishery; serve as corridors for shipping and transportation; and support ecosystems that help to improve water quality. Maintaining these aquatic ecosystem services requires a low level of chemical inputs from the upstream areas that comprise their watersheds.

Aquatic ecosystems are especially sensitive to nitrogen and phosphorus, which are key nutrients for the growth of plants, algae, and bacteria that live in these waters. High levels of these nutrients combined with our sunny weather and warm summer temperatures create conditions that can lead to rapid growth of aquatic plants and algae, which can cover these water bodies and make them no longer enjoyable for people and wildlife. It can also cause dissolved oxygen levels to fall, as plants respire (especially at night, when they are not photosynthesizing) and as bacteria consume oxygen to break down dead plant material. Low dissolved oxygen can create conditions that are deadly for fish and shellfish.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) lists more than 1,400 water bodies (including rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries) as impaired by pollutants. Many of these are impaired by excessive nitrogen or phosphorus. It is a daunting challenge to reduce pollutants in these water bodies because their inputs frequently come from all over the landscape, rather than a specific point—nutrients can come from agricultural fields, residential landscapes, septic tanks, atmospheric deposition, and livestock throughout the watershed.

In Florida, FDEP has begun a program to reduce nutrient concentrations in impaired watersheds by collaborating with landowners and other stakeholders to develop management programs to reduce pollutants entering the state’s waters. This pollutant reduction program is currently focused on Florida’s spring systems, including Jackson Blue Spring and Merritt’s Mill Pond in Jackson County. Merritt’s Mill Pond is a 4-mile long, 270-acre pond located near Marianna, and it is a popular regional destination for swimming, boating, kayaking, and fishing in the Panhandle. Its main source is Jackson Blue Spring, which produces, on average, more than 70 million gallons of water each day. Excessive growth of aquatic plants and algae in the pond during summer reduces the area available for swimming and boating. In 2014, FDEP began working with agricultural producers, residents, developers, local government officials, and other stakeholders to identify nutrient contributions in the Merritt’s Mill Pond watershed and develop an action plan to reduce nutrients entering the pond in the coming decades. Collaborations with stakeholders help to improve the accuracy of pollutant estimates, and to ensure the plan is designed appropriately to achieve desired ecological outcomes.

This Action Plan for reducing nutrients into Merritt’s Mill Pond provides an opportunity for land managers to implement their own plans to reduce nutrient contributions without FDEP imposing rigid regulations or mandating particular actions. People can choose from an array of Best Management Practices designed to reduce nutrient contributions, and the state has made funds available for people to help implement these plans. Implementing this Action Plan will restore the wonders of Merritt’s Mill through the 21st Century.

This article was written by: Matthew J Deitch, PhD, Assistant Professor, Watershed Management with the UF IFAS Soil and Water Sciences Department at the West Florida Research and Education Center. For more information, you can contact him at mdeitch@ufl.edu or 850-377-2592.

by Andrea Albertin | May 4, 2018

Special care needs to be taken with a septic system after a flood or heavy rains. Photo credit: Flooding in Deltona, FL after Hurricane Irma. P. Lynch/FEMA

Approximately 30% of Florida’s population relies on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater. This includes all water from bathrooms and kitchens, and laundry machines.

When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low. In a nutshell, the most important things you can do to maintain your system is to make sure nothing but toilet paper is flushed down toilets, reduce the amount of oils and fats that go down your kitchen sink, and have the system pumped every 3-5 years, depending on the size of your tank and number of people in your household.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

Image credit: wfeiden CC by SA 2.0

How does a traditional septic system work?

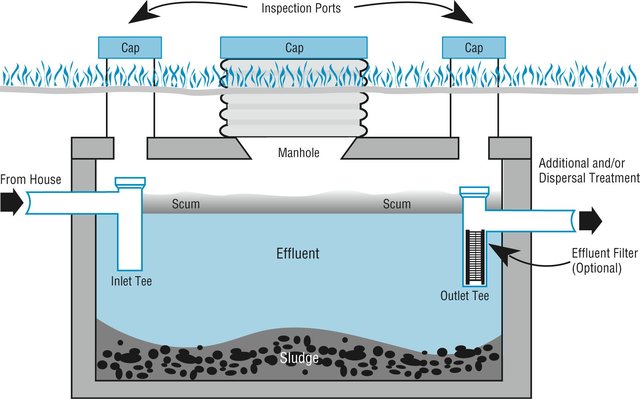

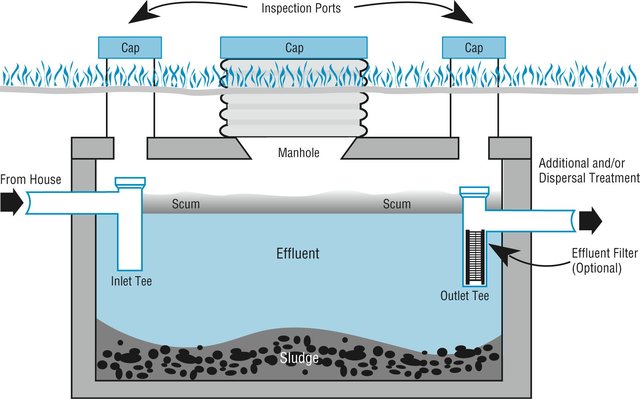

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, made up of (1) a septic tank (above), which is a watertight container buried in the ground and (2) a drain field, or leach field. The effluent (liquid wastewater) from the tank flows into the drain field, which is usually a series of buried perforated pipes. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. Bacteria break down the solids (the organic matter) in the tank. The effluent, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out of the tank and into the drain field where it then percolates down through the ground.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

What should you do after flooding occurs?

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. For your septic system to work properly, water needs to drain freely in the drain field. Under flooded conditions, water can’t drain properly and can back up in your system. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drain field while the soil is water logged. Don’t drive heavy vehicles or equipment over the drain field. By using heavy equipment or working under water-logged conditions, you can compact the soil in your drain field, and water won’t be able to drain properly.

- Don’t open or pump out the septic tank if the soil is still saturated. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened, and can end up in the drain field, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can also cause a tank to pop out of the ground.

- If you suspect your system has been damage, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drain field remains soggy and never fully drains, and/or a foul odor persists around the tank and drain field.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drain field. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain into your septic drain field – this adds an additional source of water that the drain field has to manage.

More information on septic system maintenance after flooding can be found on the EPA website publication https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/septic-systems-what-do-after-flood

By taking special care with your septic system after flooding, you can contribute to the health of your household, community and environment.

by Les Harrison | Mar 18, 2018

It is easy to notice the display of bright pink puffs erupting on low-growing trees along roadsides. This attractive plant is the Mimosa tree, Albizia julibrissin.

These once popular small trees are commonly found in the yards of older homes in Florida where the display of prolific blooms starts up as the weather warms.

This species is also classified as invasive native to southwest and eastern China, not Florida. Many Florida residents may not realize this tantalizing beauty is actually an aggressive invader in disguise.

The beautiful mimosa is found throughout the Florida panhandle.

Photo: Les Harrison

It has spread from southern New York west to Missouri south to Texas. It is even considered an invasive species in Japan.

Worse yet, mimosas are guilty of hosting a fungal disease, Fusarian, which will negatively affect many ornamental and garden plants. Some palms as well as a variety of vegetables will succumb to this pathogen.

In natural areas the invader will disrupt not only other plants, but also the birds, mammals, amphibians, and insects which depend on the displaced plants for food, shelter and habitat. Other negative traits include the disruption of water flow and aiding the incidence of wildfires.

In natural areas, mimosas tend to spread into dense clumps blocking the light to native plants which prevents them from growing. They are prominent along the edges of woods and wetland areas where seeds scatter easily and take advantage of sheltered, sunlit spots.

Mimosa tree seeds can stay viable for many years in the soil. These seeds will float without damage to their germination potential until they wash ashore to colonize a new site.

Additionally, Mimosa tree seeds are attractive to wildlife. One tree in a yard can infest many acres with the aid of birds and small mammals.

Cut or wind snapped trees quickly regrow from the stump, making this one invader that is difficult to eradicate.

Fortunately, there are a variety of small trees which can replace the Mimosa tree in home landscapes. Many are attractive, but without the unrelenting need to populate the entire subdivision.

This is a beauty-and-the-beast combo tree with too many problems to compensate for its looks.

by | Feb 18, 2017

One of the great barriers to progress in most policy discussions is an “Us” vs. “Them” battle based on historic generalizations and unawareness of change and current practices of the two “sides”. The bad news is there has been much such conflict between “farmers” and “environmentalists”, but there is good news out there. As contentious as discussions of conservation and climate change have been, agricultural practices are being driven by changing weather patterns and budget busting input and commodity prices. The beneficiary is soil and water quality and an increase in carbon sequestration.

One of the great barriers to progress in most policy discussions is an “Us” vs. “Them” battle based on historic generalizations and unawareness of change and current practices of the two “sides”. The bad news is there has been much such conflict between “farmers” and “environmentalists”, but there is good news out there. As contentious as discussions of conservation and climate change have been, agricultural practices are being driven by changing weather patterns and budget busting input and commodity prices. The beneficiary is soil and water quality and an increase in carbon sequestration.

As a recent article in the New York Times discusses, much of this change is pragmatic, not philosophical or political. With “Almost 1.7 billion tons of topsoil are blown or washed off croplands a year, according to the Department of Agriculture”, American farmers’ innovative practices are addressing a vast problem which creates “billions of dollars in losses for farmers” and untold damage to water quality.

In recent years, row crop farmers across North Florida are increasingly adopting no till planting and returning to cover crop plantings to reduce erosion, increase water infiltration, smother out weeds and keep soils cooler during our blistering summers. Here’s the story of the Florida Soil Health and Cover Crop Group’s first meeting in 2015 and its impact in one field in Jefferson county.

It wasn’t raining on April 1st, when the inaugural tour was held. Participants heard descriptions of the value of a winter cover crop,such as cereal rye, in the production of a warm season cash crop. “Discover the Cover” was hosted by Jefferson County UF/IFAS Extension, the Jefferson County Soil and Water Conservation Board, and the Jefferson County office of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service in cooperation with the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Office of Agricultural Water Policy, Brock Farms. Fulford Family Farms and Fulford 6 Farm.

Kirk Brock told of his years of experience of knocking down a cereal rye cover crop and leaving it on the field to reduce erosion, increase soil organic matter, shade out weeds and increase soil water infiltration. “We fertilize the cover crop and use that rye biomass to provide fertility for the summer crop,” Brock said. His soil pits showed attendees how rye roots penetrate the soil profile and leave channels for movement of water and crop roots to follow. “We got tired of moving our topsoil back up the hill every year,” Brock said when he explained his journey from conventional farming to no-till planting on his hilly, dry land acreage. “If I had to go back to conventional planting, I’d get out of farming,” the Jefferson County native has said.

After leaving Brock Farms, the group moved to a rye termination demonstration by members of the Fulford families. Visitors watched two different machines flatten the rye in preparation for planting. “It’ll help slow down water movement and keep the soil in the field, “grower Stephen Fulford said as the shiny new roller got its first chance to flatten Florida rye. The roller lays the mature rye down and a herbicide application insures it doesn’t get back up. Stalks aren’t severed; they remain attached to the plant’s mature roots, providing an anchored set of numerous, small obstacles to prevent water flow and soil erosion.

On a warm blue sky day, it was a little hard to visualize the effect the rolled rye might have on surface erosion. As usual, things change. I returned to the roller demonstration field on May 1 after lunch. It had just stopped raining, and the fire ant hills didn’t even have dry dirt on top of them yet. One of the wettest Aprils in history, (11.9” at the Monticello Florida Automated Weather Network station) had concluded with 3.1” of rain on the 29th and 30th. An additional 0.98” (4.08” in less than sixty hours) had fallen that morning.

Water was running down the field road, through a recently harrowed fire line and into the field. The amazing thing? The sediment went no further than three feet into the rye. The rye mat had stopped the sediment and clear water was moving slowly across the field underneath the rolled rye. The still attached rye stems remained parallel to each other.

One of the questions asked at “Discover the Cover” concerned cost effectiveness of such a system. More research needs to be done on actual costs, but one financial fact is as clear as the water at the bottom of these fields. These farmers will be planting as soon as their fields dry out. They won’t be burning any diesel to haul their topsoil back up the hill, and that good Jefferson County soil won’t be lost to the Gulf of Mexico. That’s good news for everybody.

More complete information is available on the high biomass cover crop system in the following UF/IFAS publication: Agricultural Management Options for Climate Variability and Change: High-Residue Cover Crops. If you’d like additional information on cover crop and soil health practices, contact Dr. David Wright at wright@ufl.edu or Dr. Danielle Treadwell at ddtreadw@ufl.edu.

by Sheila Dunning | Jun 3, 2016

According to the Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants, there are more than 4,200 plant species naturally occurring in the state. Nearly 3,000 are considered native. The Florida Native Plant Society (FNPS) defines native plants as “those species occurring within the state boundaries prior to European contact, according to the best available scientific and historical documentation.” In other words, the plants that grew in natural habitats that existed prior to development.

Native plants evolved in their own ecological niches. They are suited to the local climate and can survive without fertilization, irrigation or cold protection. Because a single native plant species usually does not dominate an area, there is biodiversity. Native plants and wildlife evolved together in communities, so they complement each other’s needs. Florida ranks 7th among all 50 states in biodiversity for number of species of vertebrates and plants. Deer browse on native vines like Crossvine (Bignonia capreolata), Trumpet Creeper (Campsis radicans), Yellow Jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens) and Trumpet Honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens). The seeds and berries of Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia fulgida), Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida) and Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine) provide vital food for songbirds, both local and migratory. Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) provides cover for numerous birds and small mammals, as well as, reptiles.

Non-native plants become “naturalized” if they establish self-sustaining populations. Nearly one-third of the plants currently growing wild in Florida are not native. While these plant species from other parts of the world may provide some of the resources needed by native wildlife, it comes at a cost to the habitat. These exotic plants can become “invasive”, meaning they displace native plants and change the diverse population into a monoculture of one species. Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), Popcorn trees (Triadica sebifera) and Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica) have changed the landscape of Florida over the past decade. While Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) and Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) have changed water flow in many rivers and lakes. These invasive species cost millions of taxpayer dollars to control.

By choosing to use native plants and removing non-native invasive plants, individuals can reduce the disruptions to natural areas. For more information one specific native plants that benefit wildlife go to: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw384

It learn which plants are invasive go to: http://www.fleppc.org/list/2015FLEPPCLIST-LARGEFORMAT-FINAL.pdf

by Michael Goodchild | May 22, 2016

Controlling competing vegetation and brown spot disease are two main reasons we prescribe burn young longleaf plantations:

- Longleaf pine seedlings do not like competing vegetation and will stay in the grass stage for years if vegetation is not controlled by fire, mowing or herbicides. Using improved containerized seedlings along with good vegetation management can release longleaf pines from the grass stage in 2-3 years.

- Longleaf pines are the only species of southern pines susceptible to brown spot needle blight. Seedlings are infected in the grass stage and can die from the disease. Prescribe burning is an effective method for controlling this fungus disease. Burning removes the infected needles and kills the spores. Brown spot can be identified by yellow bands on the needles, which eventually turn brown as shown below.

December thru March is the typical burn window for this activity. Older longleaf pine stands can be burned into late spring with the right weather conditions and understory. If turkey management is important to you, wait until nesting season is over to burn mature longleaf stands. We get better control of understory brush and hardwoods burning in the spring.

The link shown here shows an example of a control burn in 5 year old longleaf pine that is in the sampling stage. Good forest management practices have got these pines off to a good start. The key is not to damage the bud in the tip of pines or the newly formed candles in the spring.

*Make sure and get a burn permit from the local state forestry service before you light your fire.

References:

“Timing of Prescribed Fire in Longleaf Pine” http://www.southernfireexchange.org/SFE_Publications/etc/Clemsonforfl32.pdf

“Prescribed Burning in Newly Planted Longleaf Pine.” (Alabama Guide Sheet No. AL 338 A)