by Erik Lovestrand | Jun 30, 2017

Imagine yourself as an early settler, migrating with your family into the area known as La Florida, with the hope of staking a claim and building a new life. You’ve heard stories of horrendous mosquitos, fierce native peoples, deadly snakes, and giant alligators. Regardless, the promise of abundant fish and wildlife, a year-round growing climate and a chance to start anew, override any doubts you might have and you pack your wagon, hitch up your mules and head south with great anticipation.

Florida’s springs are world famous. They attracted native Americans and settlers; as well as tourists and locals today.

Photo: Erik Lovestrand

Well, the mosquitos have been horrendous, one of your mules was bitten by a rattlesnake but survived, and one of your hounds was taken by an alligator at a river crossing. You are in your second month of travel and you’ve come into a strange area of forest that stretches for miles in all directions. Deep, white sands clutch at your wagon wheels and make tough going for the mules. The land is forested by tall majestic pines and the terrain is gently rolling with an open view across a landscape dominated by wiry grasses and other low growing herbaceous plants. The buzzing sound of insects in the trees makes it seem even hotter for some reason and everyone is tired and thirsty as you spy a dark line of hardwood trees just down-slope. You decide to take refuge in the shade to rest the lathered mules and hope for a water source to refill your dangerously low water cask.

As you walk back under the shady canopy you find an obvious trail that has been used by other humans for generations as evidenced by a deep rut worn into the ground between exposed limestone boulders. As luck would have it, you see the glint of water through the trees ahead. When you clear the trees near the water’s edge you stop abruptly in stunned amazement. The image of a deep blue pool of crystal clear water with a small stream exiting into the woods causes you to shake your head in disbelief. You must be dreaming, as you’ve never witnessed such a magical setting; water boiling out of a gaping hole in the earth, surrounded by white sand and long flat blades of grass waving in the current.

Just about everyone who has visited one of our sparkling North Florida springs probably has a similar, magical recollection of their first encounter. As surface water percolates downward through soil layers and the porous karst (limestone) bedrock, it is filtered and cleaned to incredible clarity. The clear water gushing forth in these artesian-spring flows remains 69-70 degrees year-round in our Panhandle springs. This is due to their open aquifer connection, from which many homes draw their drinking water directly.

However, there are some serious vulnerabilities that our springs are facing regarding the quality of the water that they provide for residents and visitors alike. One issue relates to the numerous sink holes throughout our landscape that also connect directly to this same Floridan aquifer. In the past, many of these holes have served as dumping grounds for items ranging from household garbage, to junk cars, old washing machines and refrigerators, and even the occasional murder victim. Imagine all of the pollutants that end up in our drinking water supply as a result of this. Another concern relates to pollution that goes onto the ground surface and ends up in the aquifer. This happens via runoff from paved surfaces, sediments and excess fertilizers or pesticides from the landscape, or even the intentional application of treated wastewater in spray fields located in a “spring-shed.” Water clarity and quality at many of our well-known springs has suffered from excess nutrients that cause algal growth and other unwanted, nuisance plant proliferation.

As we gain a better understanding of how water moves through our landscape and ends up flowing from these natural springs, we should become better stewards by minimizing our human impacts that degrade spring water quality. Let’s keep the magic alive for all of our future generations of nature explorers.

by Judy Biss | Mar 17, 2017

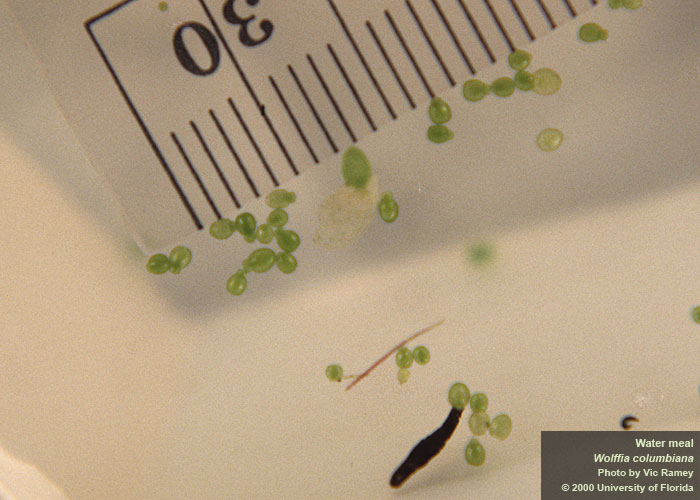

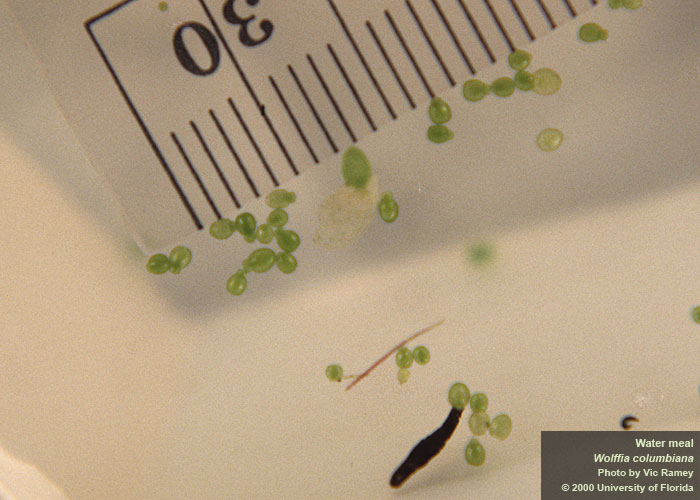

Water meal, the world’s smallest flowering plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Some of the world’s smallest flowering plants grow in aquatic environments. And a number of these tiny aquatic plants grow natively right here in Florida! Aquatic plants of all kinds display an amazing array of adaptations for growing in water. They can tolerate drought, flood, flowing water, stagnant water, cold spring runs, and warm brackish marshes. They grow in sun and shade and nutrient rich to nutrient poor waters. Some of their adaptations include the ways in which they grow such as being rooted in bottom sediments, submerged, emerged, leaves floating on the surface, or completely free floating with their roots dangling into the water below.

The tiniest of aquatic plants are in this group of free floating plants. Let’s take a look at five of these tiny (less than ½ inch wide) plant species in Florida. They are most noticeable in slow moving waters, ponds, or coves protected from wind where many thousands of them form floating mats almost like paint on the water surface. Even though individual plants are small, some of these plant species are used by wildlife and invertebrates for food and cover. Oftentimes, especially in small ponds, these tiny floating plants can cover the entire water surface resulting in the need for management, especially if the ponds are used for irrigation or livestock watering.

In this article we will look at the native species, but as you are probably aware, there are also non-native representatives of these tiny plants established in our waters, but that is a story for another time…

The images and text below are from the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Species website, list of Plants Sorted by Common Name.

Watermeal

“Water meal, native to Florida, is a tiny, floating, rootless plant. At 1 to 1.5 mm long, it is the smallest flowering plant on earth. It is occasionally found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs of the peninsula and central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003).”

Water meal has a grainy feel and can be used as one clue in identifying this plant. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

American Waterfern

“There are six species of Azolla in the world. American waterfern is the species commonly found in Florida. American waterfern is a small, free-floating fern, about one-half inch in size. It is most often found in still or sluggish waters. Young plants are, at first, a bright or grey-green. Azolla plants often turn red in color. American waterfern can quickly form large, floating mats.”

A large area of waterfern showing the reddish coloration. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Close up of individual water fern plants. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Giant Duckweed

“Giant duckweed is a native floating plant in Florida. Though very small, it is the largest of the duckweeds…..frequently found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs from the peninsula west to the central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003)… Giant duckweed has two to three rounded leaves, which are usually connected. Giant duckweeds usually have several roots (up to nine) hanging beneath each leaf. The underleaf surface of giant duckweed is dark red.”

Close up of individual duckweed plants showing roots hanging freely below the plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

A typical scene of duckweed in a quiet cove or pond. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Small Duckweed

“Small duckweeds are floating plants. They are commonly found in still or sluggish waters. They often form large floating mats…. Small duckweeds are tiny (1/16 to 1/8 inch) green plants with shoe-shaped leaves. Each plant has two to several leaves joined at the base. A single root hangs beneath.”

This is small duckweed, note the single root below each plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

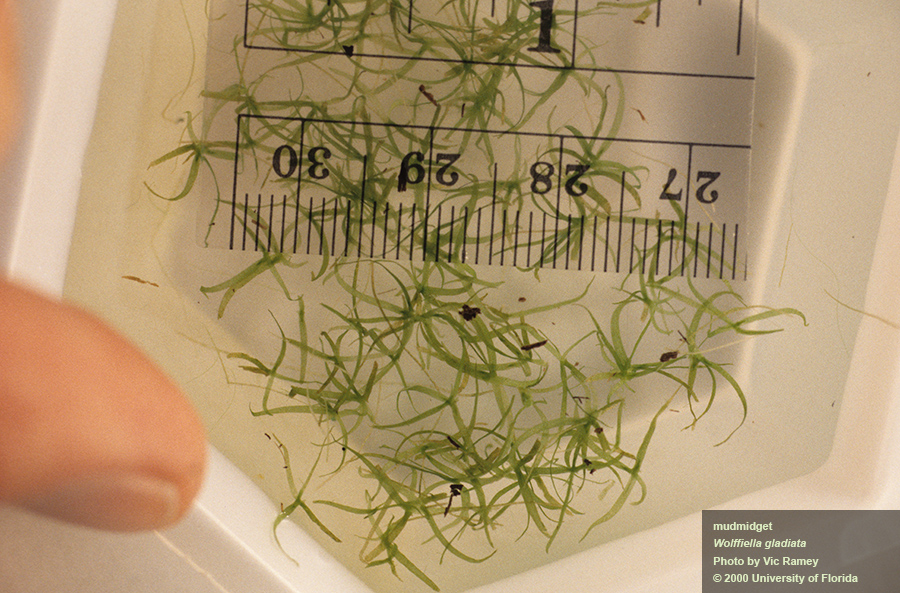

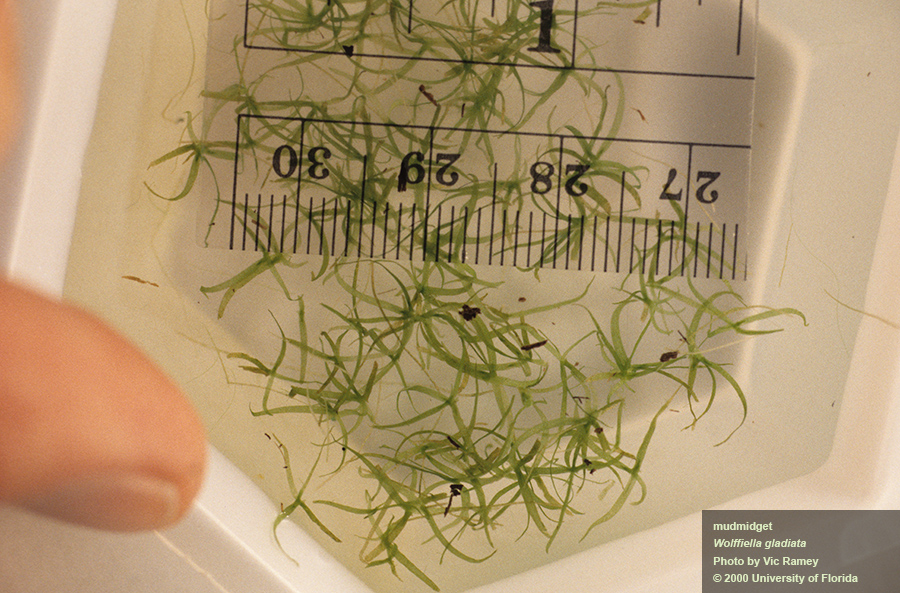

Mudmidget

“Mud-midget, native to Florida, is another small duckweed, but this one has narrow, elongated fronds. The fronds are usually connected to form starlike colonies. The fronds are 5-10 mm long; the flowers are extremely small and difficult to see. Mud-midget plants float just beneath the surface of the water and is frequently found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs from the peninsula west to the central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003)….”

Mudmidget, Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

If you have any questions about aquatic plant identification or management options, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension County office. And, for more information on Florida’s aquatic plants, please see the following resources used for this article:

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Species

Plants Sorted by Common Name

USDA Forest Service – Duckweed

USDA Forest Service – Water Fern

Native Aquatic and Wetland Plant Fact Sheets

Aquatic Plant Identification List with Pictures and Videos

by Judy Biss | Mar 17, 2017

Beaver lodge, Calhoun County Florida. Photo by Judy Biss

Even though the “work” beavers do can sometimes cause frustration to land owners, they are truly amazing creatures. A number of questions have come into the Extension Office lately about managing beavers, so it is a good time to discuss a little about the history and biology of these unique animals, as well as the management options available for land owners.

Beavers in the American Landscape

Hundreds of millions of beaver once occupied the North American continent until the 1900s, when the majority had been trapped out in the eastern United States for the fur trade (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis)). “Growing public concern over declines in beaver and other wildlife populations eventually led to regulations that controlled harvest through seasons and methods of take, initiating a continent-wide recovery of beaver populations.” (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis)). In its current range, the beaver “thrives throughout the Florida Panhandle and upper peninsula in streams, rivers, swamps or lakes that have an ample supply of trees.” (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Aquatic Mammals, Beaver: Castor canadensis).

Adaptations

Beavers are the largest rodent in North America. In Florida, they commonly weigh between 30 – 50 pounds. Beavers are considered an aquatic mammal, having adaptations such as a streamlined shape, insulating fur, ears and nostrils that close while underwater, clear membranes that cover their eyes while underwater, large webbed feet, and a broad flat rudder-like tail that aid in swimming. They can remain underwater for 15 minutes at a time! Their tree-cutting, bark-peeling front teeth grow continuously, and as a result, are continuously sharpened as they grind against the lower teeth. (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis), Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Aquatic Mammals, Beaver: Castor canadensis).

Habitat and Behaviors

Beavers typically mate for life and live in family groups consisting of the adult male and female, and one or two generations of young kits before they are old enough to disperse on their own. They are primarily nocturnal, being active from dusk to dawn. Beavers eat not only tree bark, leaves, stems, buds, and fruits, but herbaceous plants as well. Their diet is broad and can consist of aquatic plants, such as cattails and water lilies, shrubs, willow, grasses, acorns, tree sap, and sometimes even cultivated row crops. (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis)).

Top of beaver dam in Calhoun County FL. Water level difference is nearly 3 feet. Photo by Judy Biss

Dam and Lodge Construction

The sound of moving water triggers beavers to build, repair, or maintain their dams. (Baker, B.W., and E.P. Hill. 2003. Beaver (Castor canadensis)). The two main structures they build are the water-slowing dam and their living quarters or lodge. The lodge is separate from the dam and is oftentimes located in the stream or pond bank. “The ponds created by dams also provide beavers with deep water where they can find protection from predators — entrances to dens or lodges are usually underwater. Some beavers in Florida do not build the massive stick lodges associated with northern colonies. Instead, they are more likely to live in deep dens in stream banks…” Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Aquatic Mammals, Beaver: Castor canadensis).

Pear tree felled by beaver in Calhoun County FL. Photo by Judy Biss

Impacts

Beavers are called “nature’s engineers” for good reason. Their tree cutting and building behaviors certainly alter surrounding landscapes. Outside of any connection to human civilization, their activities tend to increase diversity and habitat options for both plants and animals. Many scientists have examined the intricate biological and ecological effects beavers have on surrounding landscapes. Their activities in our backyard, however, do not always result in positive outcomes. Often, beavers are triggered to build dams in running water through road culverts causing significant impacts to road drainage, and surrounding flood management. Their construction of dams along creeks can flood farm fields and woodlands. Their feeding and tree cutting can kill desired trees in nearby timberland and orchards.

Management Options for Land Owners

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) publication, “Living with Beavers” provides excellent advice, along with a summary of the regulations regarding this native wildlife species. As per this document, “The beaver is a native species with a year-round hunting and trapping season in Florida.” Beaver hunting and trapping regulations can be found on the FWC Furbearer Hunting and Trapping website. A beaver can be taken as a nuisance animal, if it causes or is about to cause property damage, presents a threat to public safety, or causes an annoyance in, under, or upon a building, per Florida Rule 68A-9.010.” Other recommendations from this FWC publication are:

- “Beaver dam removal provides immediate relief from flooding and can be the simplest and cheapest way of dealing with a beaver problem. However, beavers often quickly rebuild a dam as soon as it is damaged. “

- “When removing a dam is infeasible or unsuccessful, installing a water level control structure through the dam can allow for the control of water flow without removing the dam. This technique also reduces the likelihood of the beaver continuously blocking water flow. For technical assistance, contact a wildlife assistance biologist at a regional FWC office near you.”

- “If a beaver dam is blocking a culvert or similar structure, installing a barrier several feet away from the culvert can be the most effective solution. This prevents the beavers from accessing the culvert to dam it. Please contact a wildlife assistance biologist at a regional FWC office near you for technical assistance.”

- “Protect valuable trees and vegetation from beaver damage by installing a fence around them or wrapping tree trunks loosely with 3-5 feet of hardware cloth or multiple wraps of chicken wire. This prevents the beavers from chewing on the trees and other plants.”

- “Lethal control should be considered a last resort.”

FWC also points the reader to this publication from Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service, Department of Aquaculture, Fisheries and Wildlife, “The Clemson Beaver Pond Leveler.” This publication provides diagrams and a list of materials needed to construct a device which is designed to “minimize the probability that current flow can be detected by beavers, therefore minimizing dam construction.”

All questions regarding beaver management should be directed to your local FWC Regional Office. Land owners can also request a list of Nuisance Wildlife Trappers available in their area:

FWC Northwest Region Office

3911 Highway 2321

Panama City, FL 32409-1659

(850) 265-3676

Links to the references used for this article:

by Les Harrison | Jan 27, 2017

Recent rains have water standing on some Wakulla County real estate, which has been dry for several years. Ponds, natural and dug, are brimming with water reflecting the generous outpouring from the slow and wet weather system, which passed listlessly over the county.

Cypress swamp in Jackson County.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The rainwater excess is also filling the natural low points known as swamps or wetlands.

A swamp is defined as a forested wetland. Some occur along the flood plain of rivers, where they are dependent upon surplus flow from upstream and from local runoff.

Other swamps appear adjacent to ponds in shallow depressions, which fill during wet periods. Their landscape is covered by aquatic vegetation or trees and plants, which tolerates periodical inundation.

Historically, swamps have an image problem. Legend has all sorts of unsavory creatures, degenerates, and ghost inhabiting the locale waiting for the unsuspecting traveler.

Even the proper British used the term as a pejorative to describe Francis Marion during the American Revolution. The Swamp Fox engaged in guerilla warfare against the conventional forces and hid in the swamps to avoid capture.

Economically, these watery regions have had very low values. Their only significance was as site for trapping, hunting or for logging in dry years.

Medically, swamps were seen as a quick and painful way to the grave. There were all those creatures, which could inflict pain, leeches, snakes, gators and the like.

Then there was disease. As an example, the term Malaria originated from the swamps of southern Europe where it meant bad air in medieval Italian. The mosquito connection was unknown until the early 20th Century.

Hollywood piled on the problem with a series of swamp monster movies. One, “The Creature from the Black Lagoon” was partially filmed at Wakulla Springs.

Reality, as is often the case, is quite different from the initial perception. Even the term swamp has fallen out of favor in some circles, being replaced with wetlands.

Swamps or wetlands serve a variety of functions in the panhandle. Possibly the most critical is as a filtration system for the water table.

Excess rain is held in these shallow depressions and allowed to percolate or filter slowly through the soil. The screening effect of the soil and subsoil layers along with the slow progression cleanses the water of numerous impurities from the surface.

Without the holding capacity of local swamps, most rainwater would end up in streams and rivers. In addition to being a loss for the water table, the excess water would cloud waterways with a glut of surface debris and nutrients.

Large bald cypress trees serve as wildlife habitat at Wakulla Springs State Park. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

It is true mosquitos favor the still swamp waters, but so do many birds, fish and animals. Swamp rookeries are the nesting home for many wading birds. Mosquito larvae are an important link in the food chain, which supports much of the life in the swamp, and beyond.

Even some of the swamp’s most ostracized residents, snakes, have an important part to play in the overall environmental balance. These reptiles control the population of many destructive insects and rodents.

To learn more about the importance of swamps and wetlands, contact your UF/IFAS County Extension Office.