by Brooke Saari | Feb 28, 2014

National Invasive Species Awareness Week

Considered one of the top six biodiversity hotspots in the country, Northwest Florida contains many unique upland, wetland, and marine habitats which house a variety of plants and animals. Invasive species are non-native or exotic species that do not naturally occur in an area and cause harm to the environment, human health, and the economy. These invasive species have become the primary threat to biodiversity on protected lands. Because invasive species do not know boundaries, public and private lands are affected, as well as natural and man-made water bodies and associated watersheds. In Florida there are over 500 non-native fish and wildlife species and over 1180 non-native plant species that have been documented. These exotic species are able to out-compete many native species, causing habitat degradation, wildlife community imbalances, and diseases that can destroy economically important plants. This is a worldwide issue that can be addressed on local levels.

One of the most effective ways to control invasive species is by prevention—by simply becoming invasive-aware, you can help to control some of these issues. Recreationalists such as boaters, fishermen, pet owners, gardeners, hikers and travelers can unknowingly spread invasive species. You can take some of the following steps to avoid this dispersal:

- Cleaning and draining your boat, gear, and trailer between water bodies can stop the spread of species that may be hitchhiking on your equipment.

- If you have a pet that you are unable to keep, it is important to not release it into the wild, which can cause more harm than good to your pet and the native wildlife. Neither native nor exotic pets should ever be released. Follow the simple tips at http://www.habitattitude.net/ for alternatives to releasing your pet.

- When enjoying nature while biking, hiking, camping, birding, or other activities, be aware of the habitat where you are trekking and check what might have attached to your clothing to make sure you do not end up being an unwitting disperser.

- Gardeners, even you can help—especially when dealing with non-native plant dispersal. Not all non-native plants are bad, but make sure that the plants you put in your garden are not harmful invaders that can make it into natural areas. Verify that your plants do not occur on the invasive plant list, which can be found at http://www.fleppc.org/.

There are many ways to get involved in the battle against invasive species. Six Rivers Cooperative Invasive Species Management Areas (CISMA) is providing education and awareness for National Invasive Species Awareness Week from March 1st-9th. For more information about this awareness initiative, please visit http://www.nisaw.org/. Landowners can join their local CISMA group at http://www.floridainvasives.org/. For more information on local invasive species, contact your UF/IFAS extension office at www.solutionsforyourlife.ufl.edu. Follow our posts and articles this week at https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/.

For more information on marine science and natural resources information, email or call bsaari@ufl.edu or 689-5850.

by Mark Mauldin | Feb 20, 2014

As Floridians we often struggle to find any upside to these cold, gray days we’ve been experiencing past few months. As “unfloridian” as our winters can be they pale in comparison to those endured by the more northern states. In fact, the last days of winter can be the ideal time of year in the Panhandle to tackle some outdoor chores like controlling unwanted trees and other woody plants.

Controlling trees can be hard work, the cooler temperatures can make the task a little less taxing. The relative inactivity of the “creepy crawlies” and pests often found in wooded areas is another reason to consider completing tree and woody plant removal projects during the winter.

Tree control generally involves mechanical removal. In some cases mechanical removal provides only short term control; in other cases it can actually increase the number of unwanted plants over time. This is the problem with both Chinese tallow (popcorn tree) and privet. Herbicide treatments can eliminate the possibility of regrowth and provide permanent control. The herbicide application techniques used to control trees and other woody plants are very selective and they are effective during the winter. These techniques provide opportunities to use herbicides in a controlled and very targeted manner with very little risk to surrounding plants. Additionally, the techniques below are most effective through the fall and winter when sap flow in trees is lessened.

For best results the cut stump treatment should be done immediately after the tree has been cut down. Photo courtesy of Mark Mauldin.

The cut stump technique is a fairly common and very effective method of achieving permanent control of woody plants. As the name implies, the first step in the cut stump technique is to cut down the tree. Immediately after cutting down the tree spray or paint the stump with herbicide. On smaller stumps the entire surface should be covered with herbicide; on larger stumps effective control can be achieved by only covering the outside three inches of the stump.

With the basal treatment, cover the bottom 12 to 18 inches of the tree with the herbicide oil mixture. Be sure to cover the entire circumference of the tree. Photo courtesy of Mark Mauldin.

Two additional herbicide application techniques that work well on woody plants do not require the plants to be cut down first. The basal application technique works best on smooth barked woody plants with a diameter of less than six inches. This technique involves spraying the bottom 12 to 18 inches of the tree with an herbicide oil mixture.

The hack and squirt method works well on large and/or thick barked trees. This technique involves using hatchet or other tool to cut through the bark around the circumference of the tree, then applying herbicide directly to the cut. Several months should pass between herbicide application using either of these techniques and mechanical removal.

The hack and squirt treatment is best for large and/or thick barked trees. Photo courtesy of Mark Mauldin.

Be sure to read and follow the label of any herbicide you use. Always wear the proper personal protective equipment. For more information on the techniques described, including recommended herbicides and rates, read Herbicide Application Techniques for Woody Plant Control or contact your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Office.

by Brooke Saari | Feb 8, 2014

The Choctawhatchee Beach Mouse is one of four Florida Panhandle subspecies classified as endangered or threatened. Beach mice provide important ecological roles promoting the health of our coastal dunes and beaches. Photo provided by Jeff Talbert

Sea Turtles are one of the largest and most beloved animals associated with Florida coastal habitats. However, there is a tiny creature that depends on the coastal dune system that few get a chance to see, the beach mouse. As the name implies, beach mice make their home on beaches and in nearby dunes. These mice are a subspecies of the oldfield mouse. There are eight subspecies, five on the Gulf Coast, two on the Atlantic, and one extinct species.

The Florida Panhandle has four beach mouse subspecies: (in order from East to West) St. Andrew beach mouse, Choctawhatchee beach mouse, Santa Rosa beach mouse, and the Perdido Key beach mouse. Beach mice utilize the primary and secondary dunes for food, water, cover, and raising young. They have many burrows throughout the dunes and forage on seeds, fruits of beach plants, and insects. Beach mice are most active during the night and considered to be nocturnal. Under the cover of darkness, they make several trips in and out of their burrows to find and cache food. Feeding activities of beach mice disperse seeds and plants, adding to the health of the dune ecosystem.

Worldwide, the biggest threat to ecosystem biodiversity is habitat loss and fragmentation. Since beach mice are dependent on one specific type of habitat, it makes them susceptible to natural and human created disturbances. Due to loss of their primary and secondary dune habitats, all the beach mice except for one are classified threatened or endangered. The Santa Rosa beach mouse is the only subspecies that is not listed as threatened or endangered due to most of their habitat being protected within conservation lands on Santa Rosa Island.

Beach mice populations are continually monitored to track movement, growth, and reproduction. The common method for population counts is through the use of traps and track tubes that record mice tracks. Track indices have been developed to estimate mouse abundance.

Choctawhatchee Beach Mouse photographed during research effort in South Walton County. Photo by Jeff Talbert

A collaboration of three state agencies just concluded a five day population study of the Choctawhatchee beach mouse in south Walton County. The purpose of this effort was to study the movement in heavily (beach mice) populated areas and the effects of non-native predators on those populations. Predators specifically studied were feral cats, foxes, and coyotes. The study also evaluated the 2011 re-introduction of 50 beach mice, from the Topsail Hill Preserve State Park population into the Grayton Beach State Park population. Reintroduction was done to boost numbers of the mice in that area and expand the gene pool for the subspecies.

The data from the current effort is still being analyzed but positive results are expected due to healthy beach mice being found in areas of focus and some new areas. Public lands such as parks and wildlife refuges are important for the preservation of beach mice as well as other coastal dune species that utilize similar habitats. It is important that awareness be shared on these and other species to help these efforts to keep our habitats safe and healthy.

For more information on marine science and natural resources information, email or call bsaari@ufl.edu or 850-689-5850.

by Judy Biss | Feb 7, 2014

Photo by Judy Ludlow

The UF/IFAS Panhandle Agriculture Extension Team will once again be offering a Basic Beekeeping School in February and March. These classes will be offered via interactive video conferencing at Extension Offices across the Panhandle. Details are listed below, please call your local UF/IFAS Extension Service to register and if you have any questions. See you there!

- These classes will be taught by Dr. Jamie Ellis and other state and nationally recognized beekeeping experts from the University of Florida Honey Bee Research and Extension Lab and the Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services Bureau of Plant and Apiary Inspection.

- There will be three Monday-evening and one Tuesday evening interactive video conferences from 6:00 – 8:00 pm Central time, (7-9 pm Eastern time) and a Saturday bee-yard field day.

- Each 30-50 minute presentation will be followed by a question/answer period

February 24: Honey Bee Biology and Anatomy

March 3: Varroa Mite Biology and Control

March 10: Honey Bees of the World and Beekeeping History

March 15: Bee-Yard Field-Day – A hands on teaching opportunity

March 18: Yearly Management of the honey bee

- The cost for all five classes is $25 per person or $40 for a family. This fee will cover course materials and refreshments.

- Deadline to register is February 17, 2014. Please contact your local UF IFAS Extension office to register or to find out more details, or click on the following link for a printer-friendly flyer: 2014 Beekeeping in Panhandle

Bay County 850-784-6105

Calhoun County 850-674-8323

Escambia County 850-475-5230

Franklin County 850-653-9337

Gadsden County 850-875-7255

Gulf County 850-639-3200

Holmes County 850-547-1108

Jackson County 850-482-9620

Jefferson County 850-342-0187

Leon County 850-606-5202

Liberty County 850-643-2229

Okaloosa County 850-689-5850

Santa Rosa County 850-623-3868

Wakulla County 850-926-3931

Walton County 850-892-8172

Washington County 850-638-6180

by Judy Biss | Feb 2, 2014

Even though adapted to weather extremes, these migratory American goldfinches (Spinus tristis) appreciated the food and cover provided in this backyard. Photo by Judy Ludlow

North Florida experienced a weather delight (or distress depending on your point of view!) this week in the form of freezing rain and snow! The words “Florida” and “snow” are two words most people would not place together in the same sentence, but you may be surprised to learn that snow has been documented a number of times in Florida as revealed by records as early as 1891. In Tallahassee, measurable snow has not fallen since 1989.

The following information is taken from the National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office Tallahassee, FL about the history of Snowfall in Tallahassee: Several winters ago, NWS Tallahassee Climate Focal Point, Tim Barry, responded to an inquiry from a reporter concerning snow climatology in Tallahassee. Some of those questions and answers are listed below.

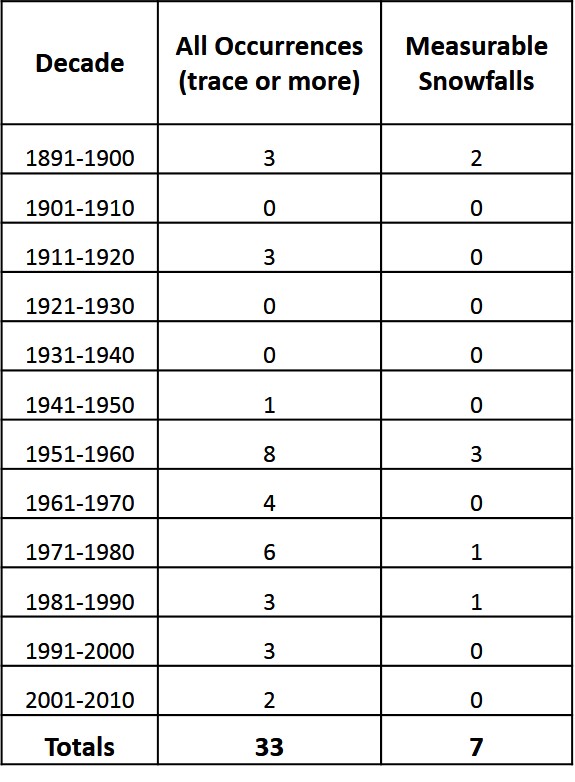

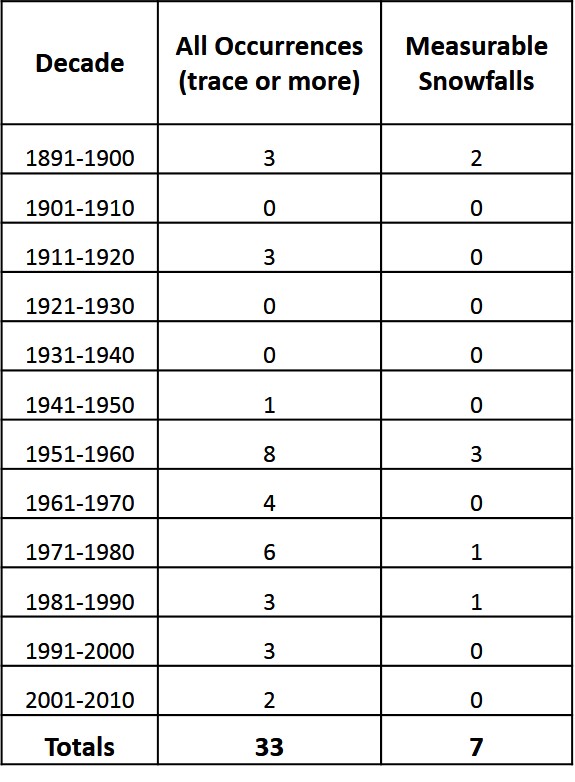

In ten-year intervals, how many times has it snowed in Tallahassee Florida?

How frequently does Tallahassee see snowfall?

How frequently does Tallahassee see snowfall?

From the information provided in the 1st question, we see that it snowed 32 times in Tallahassee since 1891. Please note that all but 7 of these occurrences were only Trace amounts. If we were to divide the period of record (117 years) by 32 we would get a frequency of once every 3.66 years. But as you can see from above, the more frequent occurrences of snow in the 50’s ,60’s and 70’s have skewed the results. The return period for measurable snow is just once every 17 years. The most snow recorded in a 24-hour period was 2.8″ from February 12th – 13th, 1958.

Any interesting or exciting facts about Tallahassee winters?

There is a significant difference between the climate of north Florida and the southern portions of the peninsula. On average, we experience 35 days with minimum temperatures at or below freezing with most of these occurring from December through March. The coldest temperature ever recorded in Tallahassee was -2 F on February 13th 1899. More recently, we dipped down to 6 degrees F on January 21st, 1985.

Florida’s wildlife, although adapted to Florida’s weather, will thrive given the added boost of backyard habitats planned for their benefit, especially during these winter weather extremes! During the winter, Florida’s native, resident, wildlife species are also joined by species which are here temporarily as they migrate through our state. The hundreds of American goldfinches (Spinus tristis) outside my window are one example.

Do you see the red cardinal in the shrub? A variety of cover strategically placed near food sources helps minimize predation and provides protection from weather extremes. Photo by Judy Ludlow

When growing your backyard habitat, think about recreating features which are naturally provided in undisturbed habitats, but only on a smaller scale. To flourish, wildlife need adequate nutritious foods, functional cover, and clean water. Locating food close to cover minimizes the exposure of foraging wildlife to severe weather conditions and to predation; these two factors account for a large percentage of mortality. Cover comes in the form of trees, shrubs, brush piles, etc. of varying heights and sizes.

Brush piles such as this one provide valuable wildlife habitat for many species. Photo by Judy Ludlow

The following information is from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s publication: Planting a Refuge for Wildlife.

Cover: Breeding, nesting, hiding, sleeping, feeding and traveling are just a few of the necessary functions in an animal’s life which require protective cover or shelter. Often plants used for cover double as food sources. Strategic placement of cover is very important in that it reduces exposure to weather extremes and provides escape from predators.

Food: All animals get their energy for survival from plants or other animals. The ideal wildlife management plan uses natural vegetation to supply year-round food – from the earliest summer berries to fruits that persist through winter and spring (such as sweetgum, juniper and holly). You will attract the widest variety of wildlife to your land by using native plants to simulate small areas of nearby habitat types. The “edges” where these habitat types meet will probably be the most visited areas in your neighborhood.

The boundary between two habitats such as between this lawn and small wooded area, creates an “edge effect” which is important to wildlife. Photo by Judy Ludlow

If you are interested in learning more about this topic, please read the following publications and, as always, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agent if you have any questions.

Planting a Refuge for Wildlife

Landscaping for Wildlife

A Drop to Drink

Eight Ways to Double the Bird Species at Your Feeders

Landscaping for a Song

Making Your Backyard a Way Station for Migrants

On Your Own Turf

Plant Berry Producing Shrubs & Trees

Plant Wax Myrtles

There’s Life in Dead Trees