by Les Harrison | Mar 18, 2018

It is easy to notice the display of bright pink puffs erupting on low-growing trees along roadsides. This attractive plant is the Mimosa tree, Albizia julibrissin.

These once popular small trees are commonly found in the yards of older homes in Florida where the display of prolific blooms starts up as the weather warms.

This species is also classified as invasive native to southwest and eastern China, not Florida. Many Florida residents may not realize this tantalizing beauty is actually an aggressive invader in disguise.

The beautiful mimosa is found throughout the Florida panhandle.

Photo: Les Harrison

It has spread from southern New York west to Missouri south to Texas. It is even considered an invasive species in Japan.

Worse yet, mimosas are guilty of hosting a fungal disease, Fusarian, which will negatively affect many ornamental and garden plants. Some palms as well as a variety of vegetables will succumb to this pathogen.

In natural areas the invader will disrupt not only other plants, but also the birds, mammals, amphibians, and insects which depend on the displaced plants for food, shelter and habitat. Other negative traits include the disruption of water flow and aiding the incidence of wildfires.

In natural areas, mimosas tend to spread into dense clumps blocking the light to native plants which prevents them from growing. They are prominent along the edges of woods and wetland areas where seeds scatter easily and take advantage of sheltered, sunlit spots.

Mimosa tree seeds can stay viable for many years in the soil. These seeds will float without damage to their germination potential until they wash ashore to colonize a new site.

Additionally, Mimosa tree seeds are attractive to wildlife. One tree in a yard can infest many acres with the aid of birds and small mammals.

Cut or wind snapped trees quickly regrow from the stump, making this one invader that is difficult to eradicate.

Fortunately, there are a variety of small trees which can replace the Mimosa tree in home landscapes. Many are attractive, but without the unrelenting need to populate the entire subdivision.

This is a beauty-and-the-beast combo tree with too many problems to compensate for its looks.

by hollyober | Mar 18, 2018

Bats sometimes move into buildings when they can’t find the natural structures they prefer (caves and large trees with cavities).

All 13 species of bats that live in Florida sleep during the day and feed on insects throughout the night. Most of these bats sleep in natural structures such as trees and caves. But when the natural structures these bats prefer are limited or vandalized, the bats may move into buildings.

Bats are a great help to us. Each of them consumes hundreds of insects per night. Bats save growers billions of dollars annually by reducing insect pests. Some of the pests bats feed on include the damaging fall armyworm, cabbage looper, corn earworm, tobacco budworm, hickory shuckworm, and pecan nut casebearer. But both bats and humans are happier when not sharing living spaces!

If you or someone you know has a group of bats living in a building where they are not welcome, you have options. The safe, humane, effective way to coax a colony of bats out of a building permanently is through a process called an ‘exclusion’. A bat exclusion is a process that prevents bats from returning to a building once they have exited at sunset to feed. This is accomplished by installing a temporary one-way door. This one-way door can take many forms, but the most common is a sheet of plastic mesh screening (with small mesh size of 0.125 x 0.125 inches or less) attached at the top and along both sides of the sheet, and open on the bottom. Another option is to install slick tubes (such as clean caulk tubes) to such entry points. These temporary one-way doors should be attached over each one of the suspected entry/exit points bats are using to get in and out of the building.

It is illegal to harm or kill bats in Florida. However, excluding bats from a building is allowed if you follow practices recommended by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). According to Florida law, all bat exclusion devices must be left in place for a MINIMUM of 4 consecutive nights with temperatures above 50⁰ F before each entry point can be permanently sealed to prevent bat re-entry. Also, it is unlawful in Florida to attempt to exclude bats from a building between April 15 and August 15, which is bat maternity season. This is when female bats form large colonies and raise young that are unable to fly for their first few weeks of life. If bats were excluded during this time period, young bats (pups) would die indoors.

Bats can be coaxed to leave a building by first identifying the bat’s entry points into the building, and then creating a temporary one-way door using plastic screening with fine mesh size over each of these entry points.

The steps for an effective exclusion are as follows:

- Identify the locations where bats are getting in and out of the building. Look for holes or crevices about the width of your thumb, often near the roofline, with brown staining on the exterior of the building and bat scat (guano, about the size of a grain of rice and brown in color) below.

- Fashion and install one-way doors at each suspected bat entry point. This can be done anytime between August 16 and April 14 – it cannot be done when bats have young pups, which is between April 15 and August 15.

- Leave all one-way doors in place for at least 4 consecutive nights with minimum temperatures above 50⁰ F so all bats leave through the doors and cannot re-enter. If any one-way door becomes ineffective during the 4 day period, begin again. You must be absolutely certain all bats have exited so you do not block any inside the building.

- Immediately after removing the one-way doors, permanently seal each hole to prevent bats from getting back inside.

For detailed instructions on how to conduct a bat exclusion, see this video that features interviews with bat biologists from the University of Florida, FWC, and the Florida Bat Conservancy: How to Get Bats out of a Building.

For additional information on Florida’s bats, visit University of Florida’s bat advice or FWC’s bat website.

Remember, if you have a colony of bats roosting indoors that you want to exclude, you must either act within the next few weeks or else wait until the middle of August to coax them out. Bat maternity season in Florida runs from April 15 to August 15, and during this time no one can attempt to exclude bats from a building.

by Judy Biss | Mar 18, 2018

Adult grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella Val. Credit: Jeffrey E. Hill, University of Florida

Spring is only days away. Everywhere you look, plants of all kinds are awakening to recent rains, longer days, and fertile soils; and this includes aquatic plants as well! Florida has hundreds of aquatic plant species, and they are an often-overlooked feature of Florida’s landscape. Overlooked that is, until the growth of non-native (or even some native) species interferes with use of our waters. Some aquatic plant species can become problematic in Florida waters as their growth interferes with fishing, flood control, navigation, recreation, livestock watering, or irrigation. For these reasons, being knowledgeable about properly managing aquatic plants is important to the many uses of Florida’s waters, whether it be a state managed public waterbody, or your own backyard farm pond.

Any pest, whether plant, animal, or insect, is best managed using “IPM” or Integrated Pest Management. IPM involves using a variety of available management “tools” to control pests in an economically and environmentally sound manner. As in any IPM effort, the first thing to do is identify what is causing the problem. Next, define what your management goals are. Then, research what tools are available for you to manage the problem. And finally, devise and implement your management plan.

In this article, we will look at one of the IPM “tools” used to manage aquatic plants – the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella Val.). The use of grass carp to manage problematic levels of aquatic plants falls under the general management term of “biological control.” Biological control essentially uses one living organism to control another living organism. Grass carp have become one of the most widely recognized examples of biological control.

The Grass Carp

As the name implies, the grass carp is an herbivorous fish that eats plants. It is native to eastern Russia and China living in large muddy rivers and associated lakes, and is actually one of the largest members of the minnow family. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission the largest triploid grass carp taken in Florida was 15 years old, 56″ long and weighed 75 pounds! The grass carp has been introduced into more than 50 countries and is used as a food item in many places around the world. They are used in nearly all states of the USA to manage aquatic plants.

Introduction into the United States:

“The grass carp was considered for introduction into the U.S. primarily because of its plant-eating diet, which was thought to have great potential for the control of aquatic weeds. In 1963 the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Fish Farming Experiment Station, Stuttgart, Arkansas, in cooperation with Auburn University, imported grass carp for experimental purposes; in 1970, this fish was introduced into Florida primarily for researchers to study its ability to control hydrilla.” (Grass Carp: A Fish for Biological Management of Hydrilla and Other Aquatic Weeds in Florida). “Early release of diploid fish led to reproductive populations in several US drainage systems, including the Mississippi River and major tributaries” (Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae))

Development of the Sterile Triploid

According to the UF/IFAS publication, Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae), “Use of the fish was limited from 1970 until 1984 due to tight regulations surrounding concerns of escape and reproduction, and the potential impacts that colonization of the fish could have on native flora and fauna. These concerns led to research that developed a non-reproductive fish, which was equally effective in controlling hydrilla.” This non-reproductive fish is known as the triploid grass carp. Through a process of subjecting fertilized grass carp eggs to heat, cold, or pressure, the resulting fish have an extra set of chromosomes rendering the fish sterile. Triploid carp have the same herbivorous characteristics as the normal diploid carp, but they are unable to spawn and reproduce. Their inability to reproduce is what makes them a viable tool to manage aquatic plants, and that is because their numbers and feeding pressure can be controlled, they cannot overpopulate a waterbody, nor if they escape, will they overpopulate un-managed areas.

The growth of invasive non-native (or even some native) aquatic plant species can interfere with the many uses of Florida’s waters. This is invasive hydrilla mixed with water lilies in a Florida lake. Photo by Judy Biss

What kinds of aquatic plants do they eat?

The grass carp grazes on many types of aquatic plants, but it does have its preferences. Its most preferred aquatics plants are hydrilla, chara (musk grass), pondweed, southern naiad, and Brazilian elodea. Its least favorite aquatic plants are species such as water lily, sedges, cattails, and filamentous algae. It will, however, graze on many types of plants even shoreline or overhanging vegetation in the absence of its preferred foods. Another reason the grass carp is an effective plant management tool is because it eats many times its body weight in plant material. As stated in Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae), “every 1 lb. increase in fish weight requires 5–6 lbs. of dry hydrilla (Sutton et al. 2012), which—considering hydrilla is 95% water—is a great deal of live plant material.”

Use of Grass Carp as a Biological Control:

Integrating the use of grass carp in aquatic plant management plans is usually cost effective. In many cases involving the use of grass carp, overabundant aquatic weed infestations are first treated with an aquatic herbicide to reduce biomass. The carp are then stocked to control regrowth and to extend the time between herbicide treatments. This can be up to 5 or more years, depending on the situation. One factor in long term control is the survival of the stocked grass carp. They are not without predators as largemouth bass, otters, birds, etc. readily prey on small grass carp. Stocked fish should be at least 12 inches long to help avoid predation and provide plant control. Other considerations to factor into your management plans are the long term, yet non-specific, control that grass carp can provide. If not stocked in the correct manner, they may end up eating aquatic plants that you wish to maintain. Also, if they eat all the aquatic plants, your once clear water may become dominated by algae instead.

How can I get grass carp for my lake or pond?

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) administers the Grass Carp program for Florida. A permit is required before you can purchase carp, and only the sterile triploid carp are permitted for use in Florida. The FWC can answer many questions about the use of grass carp and if this aquatic plant management “tool” is the right one for you to use in your particular situation. In north Florida, the regional FWC office is located at 3911 Highway 2321 Panama City, FL 32409, Phone: 850-767-3638.

What do I need to know about triploid grass carp?

Cost: Triploid grass carp cost between $5 and $15 each and are usually stocked at three to ten fish per acre, resulting in costs as low as $15 per acre. In comparison, herbicides cost between $100 and $500 per acre and mechanical control may cost more than twice that.

Time: Grass carp usually take six months to a year to be effective in reducing problem vegetation, although they provide much longer term control than other methods, often up to five years before restocking is necessary. When used in conjunction with an initial herbicide treatment, control of problem vegetation can be achieved quickly, and fewer carp are required to maintain the desired level of vegetation.

Overstocking: Once stocked in a lake or pond, carp are very difficult to remove. If overstocking occurs, it may be ten years or more before the vegetation community recovers. Even after carp are removed, other herbivores such as turtles may prevent the regrowth of vegetation.

Water Clarity: Aquatic plants remove nutrients in the water. When plants are removed, nutrients may then be utilized by phytoplankton, turning the water green. Clarity may be improved by reducing or eliminating sources of nutrients into the lake such as road runoff and lawn fertilizer.

Inflows/Outflows: It is in the best interest of people stocking carp to keep them in the desired lake or pond. It is also a required condition of the permit. Any inflows or outflows through which carp could escape into other waters require barriers to prevent fish from escaping into waters not permitted.

For more information on this topic, please see the following resources used for this article:

Aquatic and Wetland Plants in Florida

Plant Management in Florida Waters

Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae),

Grass Carp: A Fish for Biological Management of Hydrilla and Other Aquatic Weeds in Florida).

Chinese Grass Carp

FWC Triploid Grass Carp Permit

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants – Aquatic Plant Control Methods

by Andrea Albertin | Mar 18, 2018

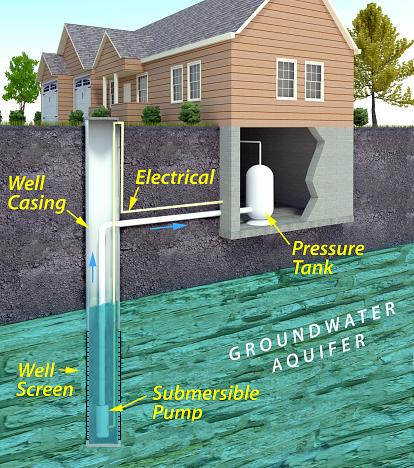

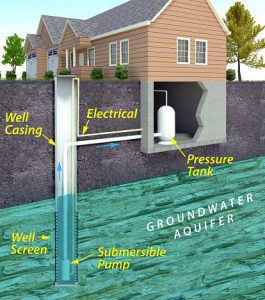

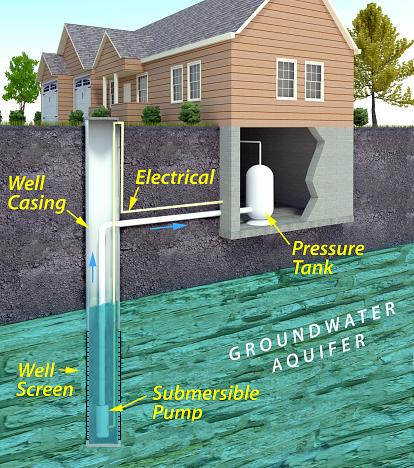

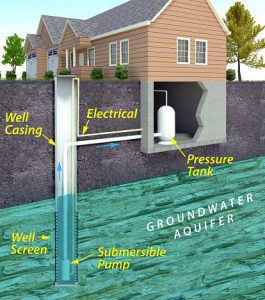

An estimated 2.5 million Floridians (approximately 12% of the population) rely on private wells for home consumption, which includes water for drinking, cooking, bathing, washing, toilet flushing and other needs. While public water systems are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ensure safe drinking water, private wells are not regulated. Private well users are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water.

Schematic of a private well typical of many areas in the U.S. Source: usepa.gov

The In Florida, pressure tanks are located above ground since basements are not common. The well casing ensures that water is drawn from the desired ground water source – the bottom of the well where the well screen is placed. The screen keeps sediment from getting into the well, and is usually made of perforated or slotted pipe. The well cap on the surface prevents debris and animals from getting into the well. Submersible pumps (shown here) are set inside the well casing and used for deep wells. Jet pumps are used on the surface and can be used for both shallow and deep wells.

How can well users make sure that their water is safe to drink?

It’s important to have well water tested at a certified laboratory at least once a year for contaminants that can cause health problems. According to the Florida Department of Health (FDOH), the most common contaminants in well water in Florida are bacteria and nitrates.

Bacteria: Labs generally test for Total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically) when a sample is submitted for bacteriological testing. This generally costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

Coliform bacteria are a large group of different kinds of bacteria and most species are harmless and will not make you sick. But, a positive test for total coliforms indicate that bacteria are getting into your well water. Coliforms are used as indicator organisms – if coliform bacteria are in your well, other pathogens (bacteria, viruses or protozoans) that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces. E. coli are one species of fecal coliform bacteria. A positive test for fecal coliform bacteria or E. coli indicate that water has been contaminated by human or animal waste.

If your water sample tests positive for only total coliform bacteria or both total coliform and fecal coliform (or E. coli), the Department of Health recommends that your well be disinfected. This is generally done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your own well can be found

Nitrates: The U.S. EPA set the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for nitrate in drinking water at 10 miligrams per liter of water (mg/L). Values above this are a concern for infants who are less than 6 months old because high nitrate levels can cause a type of “blue baby syndrome” (methemoglobinemia), where nitrate interferes with the capacity of hemoglobin in the blood to carry oxygen. It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that will be drinking well water or when well water will be used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L, never boil nitrate contaminated water as a form of treatment. This will not remove nitrates. Use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply source) until the problem is addressed.

Nitrates in well water come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are is getting into your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, make sure you contact your local health department or a water treatment contractor for more information.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Most county health departments accept samples for water testing. You can also submit samples to a certified commercial lab near you. Contact your county health department for information about what to have your water tested for and how to take and submit the sample.

Contact information for county health departments can be found on this site: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

You can search for laboratories near you certified by FDOH here: https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp This includes county health department labs as well as commercial labs, university labs and others.

You should also have your well water tested at any time when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking your well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well was affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are by no means the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your water and what they recommend you should get the water tested for. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) also maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users: http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html . This site includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 10, 2018

As we come to the end of National Invasive Species Awareness Week (NISAW), I need to educate everyone on a potential invasive threat, a classic Early Detection Rapid Response (EDRR) species – the Cuban Treefrog.

is this a Cuban Tree Frog? Do I have to rely on DNA barconding to know for sure – before I decide to euthanize it? Could I be making a mistake?

Image by Dr. Steve A Johnson 2005.

This treefrog was first introduced into to south Florida in the 1920’s. Like lionfish, it quickly became established and began its slow dispersal northward. It is a large predatory frog (reaching about 5”) which began to consume native treefrogs, reducing their populations wherever they were found. In addition to consuming native frogs, Cuban Treefrogs eat snails, millipedes, spiders, and many other small creatures. They can produce a call that is somewhat annoying to many residents where it is found. It is currently listed as established as far north as Gainesville FL.

A few years ago, I received a call from a resident near Big Lagoon in southwest Escambia County. They had just purchased plants from a local chain store to plant in their yard the following day. They had left the plants on the front porch that night and, at some point, noticed this large treefrog on their front door. They wanted to know if this was a non-native frog. It was – it was the Cuban Treefrog. The animal was collected and sent to the University of Florida.

This is a common method of transporting this frog north. They attach to ornamental plants grown in nurseries in south Florida. The plants are loaded on trucks and shipped to the panhandle and locations north and west. There are probably numerous species hitching rides this way, including the Cuban Anole (an invasive lizard). Lucky for us, in many cases these tropical problem species cannot tolerate our cold winters – this could also be said for some of the invasive plants. However, in recent years, the winters have been milder and some of these species are surviving. Most of us know and understand the impact lionfish have had on local small reef fish; no one is interested in another “lionfish problem” in the panhandle.

About a year ago, a second Cuban Treefrog was reported in Crestview.

Early this year I attended an amphibian/reptile conference in north Georgia. There was a presentation given by a scientist from the U.S. Geological Survey in Lafayette LA. He had a call from the Audubon Zoo in New Orleans about a strange frog they had been finding. They had recently purchased palm trees from south Florida for the elephant exhibit. The caretakers of the exhibit began to see strange frogs and reported it. When USGS arrived, they meandered through the park searching. They stopped by the public bathroom to look (a place I have found them in south Florida myself). They happen to pass an electric panel outside the restroom and decided to take a peak – 13 Cuban Treefrogs were within.

They began an exhaustive search and found CTFs everywhere. Most had moved into a public park between the zoo and the river called Riverview. I cannot remember how many they had found but it was in the hundreds, the animals were beginning to establish themselves in this area of New Orleans. USGS is currently working on the problem.

Just a few weeks ago, a Cuban Treefrog was found on Davenport Bayou off Bayou Grande.

There are many reports of single, individual CTFs across the northern Gulf coast, but none were established populations. However, as reports increase we should be looking for these animals and try to keep them under control before they do. No more “lionfish problems”.

How do we do this?

The following link provides information about the frog, how to identify it, how to set traps to determine if the animal is in your neighborhood, and what to do if you do find one. I would include reporting the finding on www.EDDMapS.org. I also recommend as you purchase plants for this spring’s landscaping projects, check the plants carefully for any hitchhikers. This “early detection” method is the most effective way to battle the movement of invasive species.

If you have questions about Cuban Treefrogs, let me know.

Johnson, S.A. 2017. The Cuban Treefrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) in Florida. University of Florida Extension Electronic Data Information Source (EDIS) document WEC218.

http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw259.