by Rick O'Connor | Jun 20, 2025

Despite the issues with modern agriculture, we still need food, and we need it for a lot of humans. So, what can be done to help improve things? Let’s look at some ideas that were suggested when I was teaching the class.

This is a common method used to irrigate crops across the U.S.

Photo: UF IFAS

Pesticides. There have been several methods employed to deal with the disadvantages of pesticides. One is legislation. In 1947 the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) was passed. It was amended in 1972. This law allows the EPA, USDA, and FDA to regulate the sale and use of pesticides. In 1996 congress passed the Food Quality Protection Act. This law requires the EPA to reduce the allowed levels of pesticide residues in food by a factor of 10 when there is inadequate information on the potentially harmful effects on children. However, some studies from the National Academy of Science suggest these laws are not enforced as they should be for all pesticides. There are other methods suggested by scientists to battle crop pests.

- Fool the pests. This can be done by rotating different crops on the land each year. This helps control the population of insects that feed on specific crops and reduce their impact. Another idea is to plant crops during a time of year when the pest life cycle keeps it from being a problem, or when their predators are more abundant.

- Provide a home for pest enemies. Farmers can move from monocultured fields to polyculture fields which can decrease pest populations as well as enhance their predator’s population. This is also a method that could be used to reduce pesticides needed on homeowner lawns.

- Genetically modified plants. Though controversial, this method can produce both pest whose development is sped up, and crops that are resistant to the pest.

- Biological control. Introducing natural predators will reduce the need for pesticides all together. However, it is slow acting, not always available when needed, and can become pests themselves.

- Pheromones (sex attractants). These can be used to lure pests into traps or attract their natural predators. Pheromones are species specific so will not harm beneficial insects.

- Spraying hot water. This method has had success on cotton, alfalfa, potatoes, and citrus crops in Florida.

Many experts and farmers feel the best method to control pests is what is called the integrated pest management (IPM) plan. In this method the farmers assess their situation and then develop a plan that uses a combination of the above methods including chemicals. A study by the National Academy of Science found that using IPM methods can reduce pesticide use between 50-65% without reducing crop yield or food quality. However, there are some drawbacks. 1) it does require expert knowledge about the pest situation – here Extension can help. 2) it takes more time to be effective than pesticides. 3) no one IPM plan works for all, there could be slight differences between neighboring fields. There is also the issue of government subsides to encourage pesticide use, which has slowed this method down.

Soil. There are methods that have been used by farmers around the world to reduce soil erosion.

- Is used on land that is sloped. It helps retain water and soil from washing downhill.

- Contour farming. Is another method used on sloped land. Here the plowing goes across the landscape instead of up or down.

- Strip cropping. Is a method where one row is the row crop of interest (corn or cotton) with alternant rows of cover crops (alfalfa or clover). These cover crops help hold the soil in place and reduce water runoff.

- Alley cropping. Is a method where the crops are planted between rows of trees or shrubs – which provide some shade and reduces evaporation and helps slowly release soil moisture. The selected trees can provide fruit, and leaf litter than is used as mulch.

- Windbreaks or Shelterbelts. I see this a lot. This is a method where the larger field of crops is encircled by trees to reduce wind speed and erosion. The trees help retain moisture, provide habitat for insect predators, and can be sold as a product itself.

- No till or minimum tillage. Tilling the soil is needed but can enhance wind blown erosion. There are special tillers and planting machines that can plant seeds directly into through the crop residue into the undisturbed soil.

Years of abuse have made some soils less fertile and non-productive. There are methods being used to help restore this fertility. Some of these methods include organic fertilizers – such as animal manure and green manure. Green manure consists of using plant waste plowed into the soil. Composting is an option, as are commercial inorganic fertilizers.

Sustainable Aquaculture. Many feel with the size of the human population now wild harvest seafood cannot sustain us. Mass production of seafood – aquaculture – is the direction we should move. However, in the last article we mentioned some of the problems with aquaculture. Ways to improve this would include.

- Do not place aquaculture farms in/near environmentally sensitive systems – such as mangrove forest or salt marshes. Some aquaculture projects (oysters) can actually help enhance water quality.

- Improve management of aquaculture waste. Waste treatment facilities.

- Develop methods to reduce escape of aquaculture species into the wild.

- Caged methods in existing water systems can help reduce predation and disperse waste.

Meat Production. One issue with meat production is the amount of meat we consume. Since 2011 between 30-40% of the grain grown is used to feed livestock – not humans. Miller suggests that if the world had the average U.S. meat diet, our current grain harvest would only feed about 2.5 billion people. Reducing meat in our diet would provide more grain-based foods for human consumption. They also suggest shifting from less efficient grain fed meats – beef and pork – to more grain efficient forms of meat – chicken and fish – would also improve food production in general. There are also concerns about how livestock are raised for mass production. Large, overcrowded feedlots and pens are of concern. Several major fast-food chains and grocery stores have invested in research to try and improve conditions for our livestock. I watched a cooking show hosted by an Italian women. She mentioned that they had livestock on the farm growing up. During the spring, summer, and fall they ate primarily vegetables, fruit, and non-meat pasta dishes. In the fall they would slaughter their livestock and switched to a meat diet during the winter – because that was when the meat was available. It also makes sense from a biological point of view. Your body requires higher protein-fat diets to keep warm in winter – this is not needed in the summer. Consuming more fish in summer would make sense. Many have converted to such diets and – to keep up with the growing human population – many more will need to.

References

Sloat, L., Ray, D., Gracia, A., Cassidy, E., Hanson, C. 2022. The World is Growing More Crops – But Not for Food. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/insights/crop-expansion-food-security-trends.

Miller, G.T., Spoolman, S.E. 2011. Living in the Environment. Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning. Belmont CA. pp. 674.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 20, 2025

Snails and slugs belong to one of the largest phyla of animals on the planet – the mollusks. Mollusks are known for their calcium carbonate shells and seashell collecting along the shoreline has been a popular hobby for centuries. There are an estimated 50,000 to 200,000 species of mollusk worldwide. One group – the gastropods – have an estimated 40,000 to 100,000 species alone. This is the group that includes the snails and slugs.

Snails are soft-bodied creatures who produce a single, usually coiled, shell in which they live. The coiled shell has an opening called the aperture through which they can extend some, or most of their body. The elongated soft body “slugs” across the sea bottom searching for food which could be vegetation for some – like the small nerite snails found in our bays, or animals – like the venomous cone snails, or detritivores – like the periwinkle snails.

The Olive Nerite.

Photo: Wikipedia.

Many species of local snails produce egg cases in which they deposit their developing eggs. These are often found while people are beach combing. The most frequently encountered locally are the tube-shaped clusters of the oyster drill, the coin shaped chain of the lightning whelk, and the one that – to me – resembles the top of a vase or jar belonging to the moon snail.

The egg case of the Lightning Whelk.

Photo: Project Noah

The variety of snails found in the northern Gulf is immense – so, we will cover only a few of the more common.

Walking along the Gulf side, gazing down at the shells of snails washed ashore, one often finds the small ceriths. These tiny, elongated shells are small and look like a canine tooth. These are herbivores and detritivores.

Cerith

Photo: iNaturalist

The Florida Fighting Conch is often found – but not always in whole condition. This is a true conch and herbivorous.

Florida Fighting Conch

Photo: iNaturalist

One not as common while beachcombing, but more common while snorkeling is the olive snail. These are fast burrowing snails that feed on bivalves and carrion they may find. I often find trails crisscrossing the sandy bottom made by these snails just off the beach.

Olive snail

Photo: Flickr

Over on the bay side of the barrier islands you have a better chance of finding live snails. One of the more common in the salt marshes is the marsh periwinkle. This small roundish snail is often seen on the extended leaves of the marsh grasses. It is here during high tide to avoid predators such as blue crabs and diamondback terrapins. At low tide they will descend to the muddy bottom and feed on detritus.

The marsh periwinkle is one of the more common mollusk found in our salt marsh. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The crown conch is another frequently seen estuarine snail. With spines extending from the top whorl – it appears to have a crown, and where its common name comes from. These are predators of the bay feeding on other mollusks such as periwinkles and oysters.

The white spines along the whorl give this snail its common name – crown conch.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The oyster drill shell is one of the more common shells you find hermit crabs in, but the snails are out there as well. As the name implies, they use a tooth like structure called a radula to bore into other mollusk shells to feed. They are particularly problematic for non-moving oysters – and where they got their common name from.

The shell of the oyster drill.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The only slug I have encountered on our beaches is the sea hare. These slugs can be a greenish or brownish color and are about six inches in length. They lack an external shell but do not move much faster than their snail cousins. They feed on a variety of seaweeds and the color of their skin mimics the seaweeds they are feeding on. Lacking a shell, they produce a toxin in their skin to repel would be predators. They also release ink like the squid and octopus cousins.

A common sea slug found along panhandle beaches – the sea hare.

This narrative only scratches the surface of the world of snails and slugs in this part of the world. Creating a check list of species and then seeing if you can find them all is great fun.

References

The Mollusca. Sea Slugs, Squids, Snails, and Scallops. University of California at Berkley. https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/mollusca.php#:~:text=Mollusca%20is%20one%20of%20the,scallops%2C%20oysters%2C%20and%20chitons..

Gastropods. University of Texas San Antonio. https://www.utsa.edu/fieldscience/gastropod_info.htm#:~:text=Gastropods%20are%20another%20type%20of,of%20the%20entire%20Mollusca%20phylum..

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 6, 2025

Let’s begin with crops. In 2011 it was reported that 77% of the world’s food was coming from grains being grown on 11% of the worlds land. Rice, wheat, and corn were/are the big players. We mentioned in Part 8 of this series that industrial farming of these crops was putting a heavy toll on the nutrients in the soil needed to sustain the next crop. Response… commercially produced inorganic chemical fertilizers – we will make these nutrients in a factory and spread them over the fields. Massive irrigation systems were developed to water these large fields and allow us to use land that would otherwise not be able to support these crops. Commercially produced pesticides to reduce the enormous numbers of insect pests – whose populations were also increasing with the increase in food sources. Reducing pests equals higher yield. High-yield grain varieties – science had been able to develop new strains of grains that could produce quicker and even produce their own defenses against insects. But with this success there has been a cost.

This is a common method used to irrigate crops across the U.S.

Photo: UF IFAS

There was a statement in the textbook I used when I taught this class saying – “according to many analysts, agriculture has a greater harmful environmental impact than any other human activity and these environmental effects may limit future food production”. Let’s look at some of these negative impacts.

Soil. Topsoil erosion is a serious problem in many parts of the world. Naturally the overlying vegetation holds the soil, retains water, and exchanges nutrients. When the native vegetation is removed for agriculture, the soil blows/washes away, it becomes drier, and the nutrients are not replenished. In 2011 it was estimated that 33% of the world’s cropland was losing soil faster than it was being replaced. In some locations this has been so extreme that the land has actually been converted into a desert – a process called desertification. Water used in irrigation has small traces of salt. When sprayed over a field in more arid areas – it evaporates quickly leaving behind the salt, which can kill the crops – a process called salinization. In some areas the water from irrigation causes the natural water table to rise, soaking the crops and killing them – a process called waterlogging.

Genetically Modified Food. The advances in genetically modified food have had both positives and negative results. One the positive side – many of these crops do not require fertilizers – need less water – more resistant to insects, disease, frost, and drought – they grow faster and at higher yields. The negatives include – irreversible and unpredictable genetic and ecological effects to the neighboring environment – possible harmful toxins produced by mutations of these GM plants – new allergens – lower nutrition – an increase in pesticide resistant insects and weeds – and can harm beneficial insects.

Industrialized Meat Production. Advantages include – increased meat production – less land use – reduced overgrazing – and reduced soil erosion. Negatives include – large inputs of grain, water, and energy – higher greenhouse gas emissions (methane) – high concentrations of animal waste that pollutes – and antibiotics increases genetic resistance to microbes in humans.

Pesticides. Advantages include – increased food supply. Disadvantages include – promoting genetic resistance – kills beneficial insects – can harm wildlife and humans – expensive. Studies have shown that when pesticides are used about 95% of the targeted pests are killed. However, the 5% of insects who were naturally immune to the pesticide reproduce rapidly to fill the decrease in the population. Within five or so years, most of the pests are now immune to the pesticide. So, they need to “beef up the formula”. This again kills 95% of those pests. But, again, 5% are immune – and the cycle begins again, during each round the pesticides become stronger and stronger – this process is called the pesticide treadmill. And we all have heard of the DDT story. This was a “one time spray to kill all your insect pests” – and it did. The bad insects, but the good insects, birds, and many other forms of wildlife suffered from this.

Aquaculture. Many feel the future of seafood production is in “fish farming”. They do not believe that wild harvest is sustainable with the growing population. The advantages to aquaculture include – high efficiency and high yield to small volume of water used. The disadvantages would include – requires large inputs of land, feed, and water – large waste outputs – reduces natural ecosystems – uses grain to feed some species – dense populations are vulnerable to diseases.

In Part 10 we will learn about attempts to correct some of the disadvantages – we still need food.

Reference

Miller, G.T., Spoolman, S.E. 2011. Living in the Environment. Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning. Belmont CA. pp. 674.

by Rick O'Connor | May 16, 2025

As far as familiarity goes – everyone knows about worms. As far as seeing them – these are rarely, if ever seen by visitors to the northern Gulf. Most know worms as creatures that live beneath the sand – out of sight and doing what worms do. We imagine – scanning the landscape of the Gulf – millions of worms buried beneath the sediment. For some this may be quite unnerving. Worms are sometimes “gross” and associated with an unhealthy situation. You might say to your kids “don’t dig in the sand – you might get worms”. Or even “don’t drink the water – you might get worms”. But the reality of it all is that there are many kinds of worms in the northern Gulf, and many are very beneficial to the system. We will look at a few.

The common earthworm.

Photo: University of Wisconsin Madison

Flatworms are the most primitive of the group. As the name implies, they are flat. There is a head end, often with small eyespots that can detect light, but the mouth is in the middle of the body and, like the jellyfish, is the only opening for eating and going to the restroom. There are numerous species of flatworms that crawl over the ocean floor feeding on decayed detritus, many are brightly colored to advertise the fact they are poisonous – or pretending to be poisonous. And then there are species that actually swim – undulating through the water in a pattern similar to what we do with our hand when we stick it out the window driving at high speed.

But there are parasitic flatworms as well. Worms such as the tapeworm and the flukes are more well known than the free-swimming flatworms just described. These are the worms people become concerned about when they hear “there are worms out there”. And yes – they do exist in the northern Gulf. But what some people may not realize is that these internal parasites are adapted for the internal environment of their selected host and cannot survive in other creatures. There are human tapeworms and flukes, but they are not found in the sands of the Gulf.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

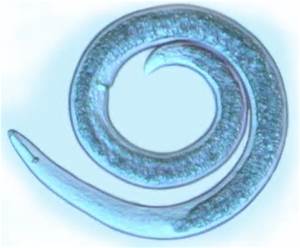

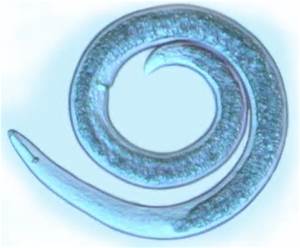

As the name implies, roundworms are round – but they differ from earthworms in that their bodies are smooth and not segmented as earthworms are. One group of roundworms is well known in the agriculture and horticulture world – nematodes. Some nematodes are also known for being human parasites – again, creating some concern. These include the hookworm and pinworm. Roundworms can be found in the sediments by the thousands – sometimes in the millions. The abundance of some species are used as an indicator of the health of the system – the more of these particular type of roundworms, the more unhealthy the system – again, a cause of concern for some when they see any worm in the sand.

The round body of a microscopic nematode.

Photo: University of Nebraska at Lincoln

We will end with the segmented worms – the annelids. This is the group in which the familiar earthworm belongs. Though earthworms do not exist in the northern Gulf, their cousins – the polychaetae worms – are very common. Polychaetas are much larger, easier to see, and differ from earthworms in that they have extended legs from each segment called parapodia. Some polychaetas produce tubes in which they live. They will extend their antenna out to collect food. Many of these tubeworms have their tubes beneath the sand and we only see them (rarely) when their tentacles are extended – or when they extend a gelatinous mass from their tubes to collect food. But there is a type of tubeworm – the sepurlid worms – that produce small skinny calcium carbonate tubes on the sides of rocks on rock jetties, pier pilings, and even marine debris left in the water. This is also the group that the leech belongs to. Though leeches are more associated with freshwater, there are marine leeches. These are rarely encountered and do not attach to humans as their freshwater cousins do.

Diopatra are segmented worms similar to earthworms who build tubes to live in. These tubes are often found washed up on the beach.

Though we may be “creeped-out” about the presence of worms in the northern Gulf of Mexico, they are none threatening to us and are an important member of the marine community cleaning decaying creatures and waste material from the environment. We know they are there, and glad they are there.

by Rick O'Connor | May 12, 2025

With 8 billion humans on this planet there is a need for a lot of space and resources. In this modern world we can get lost in which resources we really NEED and those that we really WANT. We all need a space to live, but we do not necessarily need a 5000 ft2 home, with a pool and manicured lawn – those are wants. But we do need food – and lot of it.

The most popular seafood species – Shrimp.

Thousands of years ago humans fed themselves through hunting and gathering. We hunted, as many do today, for a food source but killed only what they needed – they had no means to store/preserve food in a mobile society such as they had. Groups of humans began to settle into one general location and moved towards and different lifestyle – early agriculture. They would plant seeds and keep livestock to feed on through the course of the year. Many would grow crops but continued to hunt for their meat. They developed methods of smoking and salting meat to preserve it longer. They created large bins where crops could be stored, but most were still growing and gathering the food for their families alone.

As these small sessile communities became larger (growing population) the fields became larger and fed not just their family, but all of the families. Residents would take their livestock to the community “commons” where they could graze – since space to do so at your home was not available.

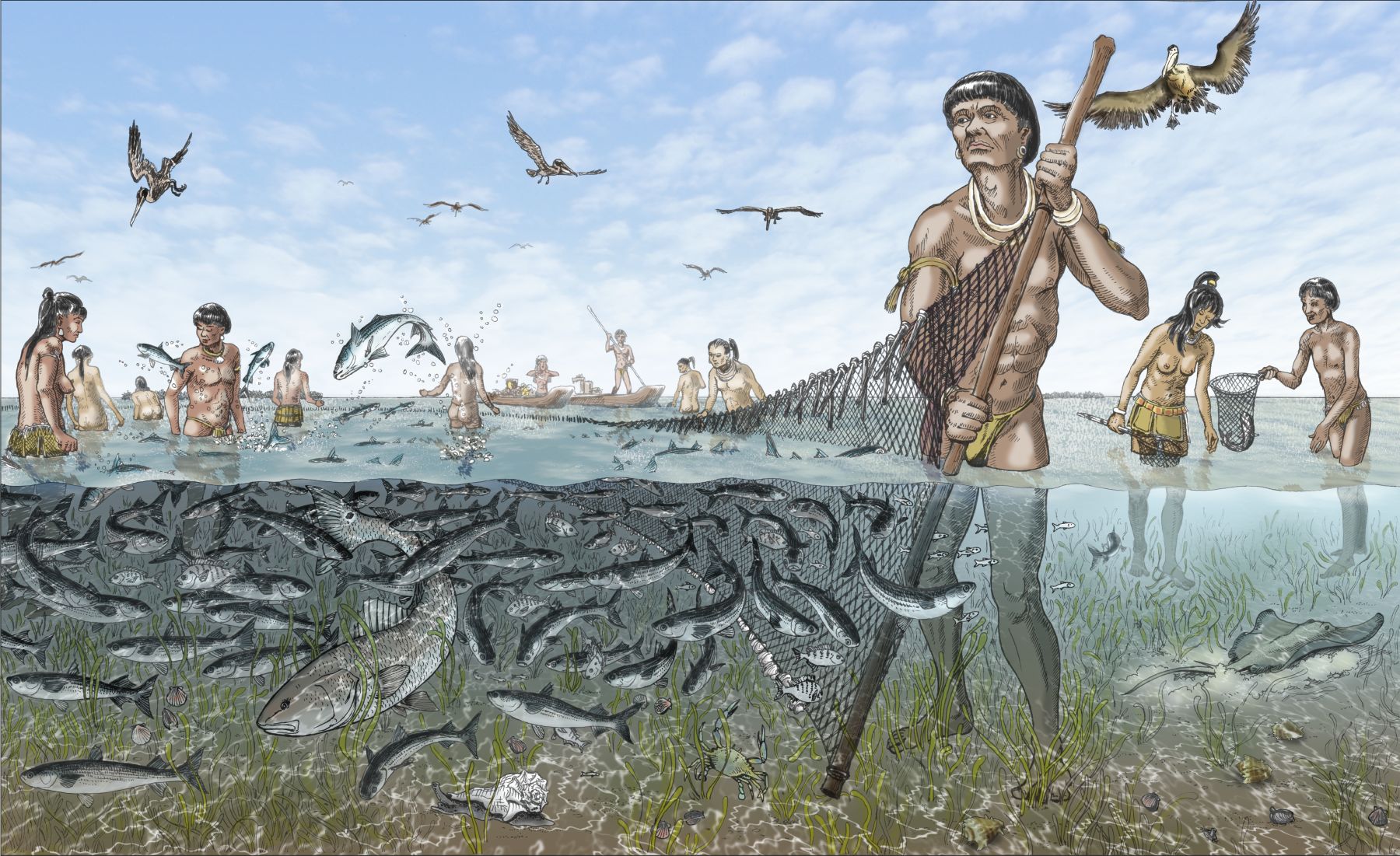

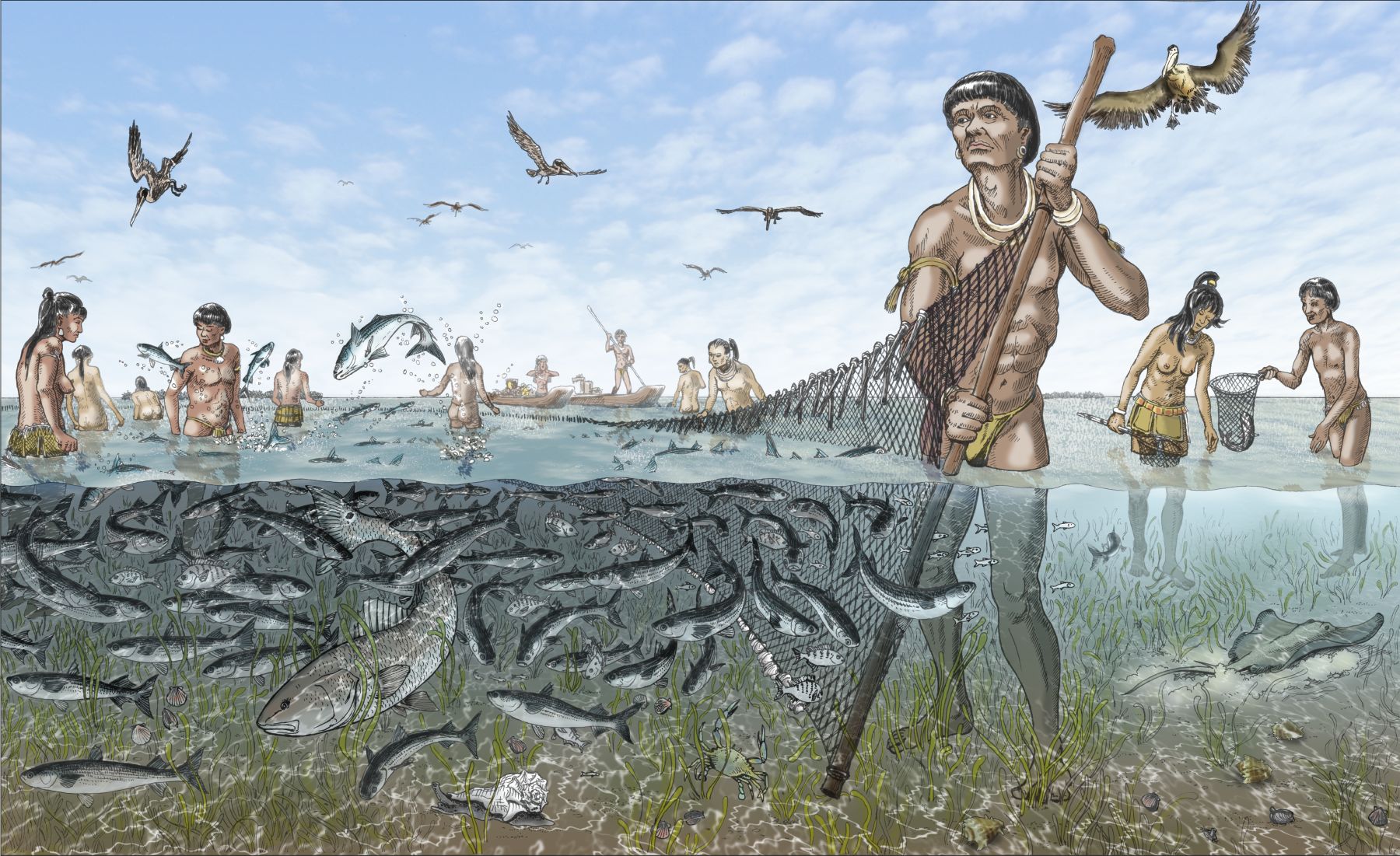

Those who lived on the coast could utilize another resource – marine resources – shell and finfish as well as seaweeds. As with farming, most fishermen began by harvesting for their families, but as the population grew, they began to harvest for others. In both cases – as populations grew, the number of farmers and fishermen grew, and the space and resource needed to sustain the growing communities grew as well.

Early fishing.

Image: University of Florida

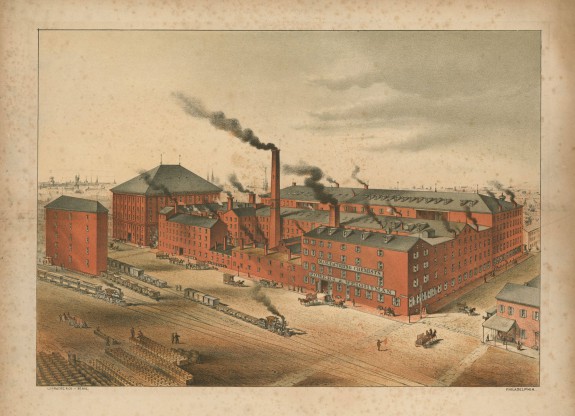

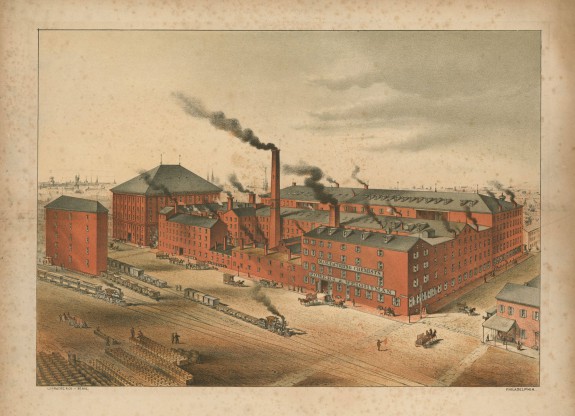

During the industrial revolution of the 19th century humans begin to develop technologies and methods that could expand farming and fishing to harvest more, more efficiently, and at a faster rate. The world was experiencing a growth in the production of all sorts of products, growth in food production increased as well. With mechanized farming and fishing, we could feed more, the human population could sustain more, and so the population grew. The exponential growth in the human population – what many refer to as the “J” curve – is closely associated with the industrial revolution – which could provide more resources to sustain this growth.

Industrial Revolution.

Image: Encyclopedia of Philadelphia.

The agriculture world began what has been called the “green revolution”. Large expansive fields, growing large amounts of crops, utilizing new machines that could keep up the work. Rice and wheat were staples – grown all over the world. Corn followed. Large expanses in land were cleared to grow these crops as well as graze cattle to help with the demand for meat. Large farms needed mechanized equipment to harvest, process, and transport these food products to markets far away from the farms themselves. Commercial fishing fleets were provided technologies that aided them with locating their target species faster, removing large amounts of fish into larger vessels quicker, and keeping them cold longer at sea to increase harvest yield. They too would need processing plants and transportation to get their products to markets far away from the sea.

Tractors planting rows of eucalyptus trees. Biomass crops, biofuel, sustainability. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones.

We began a system to feed a growing human population, and we were very successful. And as the human population continued to grow, the need for better technologies was needed – and delivered. According to the textbook I used when I was teaching this course, we were producing enough food to feed the human population, but there were three problems… (1) we were removing these resources faster than they could replace themselves. (2) when you consume resources you produce waste – this is true even in photosynthesis. As we produced more food, we were also producing more waste. And (3) one in every six people in the developing countries were still not getting enough to eat.

With agriculture they had moved to large area farms where they could plant large numbers of crops, which were harvested as frequently as possible. The stress on the soil became a problem by removing the nutrients at faster rates than mother nature could replace them. To add to the problem most fields grew the same crops, thus removing specific nutrients at a faster rate – compounding the problem. Farmers were literally working the fields to death.

Livestock moved to larger factory farms with large processing plants for larger numbers of cattle, chicken, and pigs. There was not enough space to free range cattle as they had done prior to the green revolution. So, now they were commercially fed, and this could be done in a smaller space with large numbers of animals in such. Crowding creatures like this can enhance the spread of disease and produces large amounts of waste that must be managed.

In the commercial fishing world, they were removing fish faster than nature could replace them. Many fishing grounds went “silent” as the fish populations declined forcing fleets to find new waters or new target species to harvest. We began to overfish the oceans.

Purse seining in the Pacific Ocean.

Photo: NOAA

Man’s ingenuity had developed a mechanized system for feeding their population – and it worked well. But it developed some problems both for the system and food production and for the environment as well. In the next few articles, we will look at how we are trying to resolve those problems.