by Carrie Stevenson | May 1, 2017

The Southeastern blueberry bee uses buzz pollination on a blueberry plant. Photo credit: Tyler Jones, UF IFAS.

This time of year, blueberry bushes are flowering and small fruit are coming onto the wild and cultivated bushes in north Florida. Many of us, myself included, look forward to the late-spring harvest of blueberries, taking our children out to u-pick operations and digging out family recipes for blueberry-filled desserts.

What many do not know, however, is that there’s a specialized bee that literally lives for this season. During the last few weeks, this little insect has been furiously pollinating blueberry bushes during its short, single-purpose lifetime.

The Southeastern blueberry bee, Habropoda labriosa is active only in mid-March to April when blueberry plants are in flower. They are smaller than bumblebees, and the yellow patches on their heads can differentiate males. Blueberry pollen is heavy and sticky, so it is not blown by the wind, and the flower anatomy is such that pollen from the male anther will not just fall onto the female stigma. Blueberry bees must instead attach themselves to the flower and rapidly vibrate their flight muscles, shaking the pollen out. Moving to the next flower, the bee’s vibrations will drop pollen from the first flower onto the next one. This phenomenon is called “sonicating” or ‘buzz pollination” and is the most effective method of creating a prolific blueberry crop.

Blueberry bees do not form hives, but create solitary nests in open, sunny, high ground. Females will dig a tunnel with a brood chamber large enough for one larva, filling it with nectar and pollen. After laying an egg, the female seals the chamber and the next generation is ready. The species produces only one generation of adults per year.

By the time we are picking fresh blueberries next month, you probably won’t see any blueberry bees around. However, we should all consider these insects’ short-lived but vitally important role in Florida’s $82 million/year blueberry industry!

For more information, check out the beautifully illustrated USDA Forest Service publication, “Bee Basics—An Introduction to our Native Bees,” or North Carolina State University’s entomology website.

by Julie McConnell | May 1, 2017

American Dog Tick. Photo: L. Buss, UF/IFAS

You’ve probably heard some tips to prevent picking up ticks in the past, but did you ever wonder why some work and others don’t? Understanding the life cycle and behavior of common ticks can help you succeed with your prevention measures.

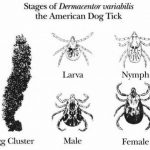

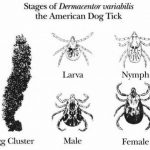

Life Cycle of American Dog Tick. Credit: Centers for Disease Control

A general life cycle for ticks includes four life stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. The egg hatches into larva which require a blood meal to molt into a nymph which again requires a blood meal before molting to an adult.

The adult female also requires blood feeding in order to produce eggs, which she lays in high numbers – some species lay up to 6,500 eggs!

Because blood is required for development, ticks have to be resourceful in finding hosts. Knowing this can help you understand why some tips work better than others.

Tick Tips

-

Wear clothing that covers skin and avoid sitting on the ground or logs in brushy areas. Adult ticks exhibit a behavior called “questing” where they climb to the top of grasses and vegetation with their forelegs extended and wait for a host to come by. The American Dog Tick‘s primary host are dogs, but they will also target cattle, horses, and humans.

-

Apply repellents to exposed skin and clothing (different products are labeled for where they are applied, follow all directions). These chemicals repel ticks and can reduce likelihood of tick attachment, but ticks have been known to crawl over treated areas to access untreated body parts.

-

Keep grass and vegetation maintained and clean up debris that may harbor small mammals and rodents. Early in the tick life cycle it targets smaller animals for blood and they can

hide or shelter in debris piles and vegetation.

-

Always shower and check yourself for ticks after being in areas where ticks may live, especially when temperatures are warm. Nymphs can be less than 1 mm long, so check carefully!

For instructions on how to properly remove a tick that has embedded, visit UF Health Tick Removal.

Female Lone Star tick that has not fed. Photo: L. Buss, UF/IFAS

Lone Star Tick female engorged on blood. Photo: L. Buss, UF/IFAS

by Beth Bolles | May 1, 2017

We may shy away from drama in our lives but drama in the garden is always welcome. One plant series that will be a prominent feature in any garden bed is the Amazon Dianthus series.

Amazon Dianthus series is showy in the garden or in a container. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

Although we normally consider Fall the time to plant dianthus, the Amazon Series developed by PanAmerican Seed company can be planted in Spring for blooms that extend into Summer. This is the combination of two dianthus and the results are plants with striking colors and longer blooming cycles.

The Amazon series comes in a few bright colors including Amazon Neon Cherry, Amazon Neon Pink, and Amazon Rose Magic. Flowers are held on stems about 1.5-2′ tall and foliage is an attractive dark green. Plants are generally low maintenance but be sure to deadhead flowers as they fade. Plants will need rich, well drained soil and full sun.

Neon Cherry. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

Neon Pink. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County

If you don’t have room for the Amazon dianthus series in your landscape, plants will also grow well in containers to brighten a patio or deck.