In the late 1700’s, explorer and naturalist William Bartram and his father, the “King’s Botanist”—visited Pensacola and much of the southeastern United States. Curious observers of everything from plant growth and wildlife to Native American culture, they were also collectors. Countless American plant species were sent to Europe for further examination and later preserved in gardens and arboretums.

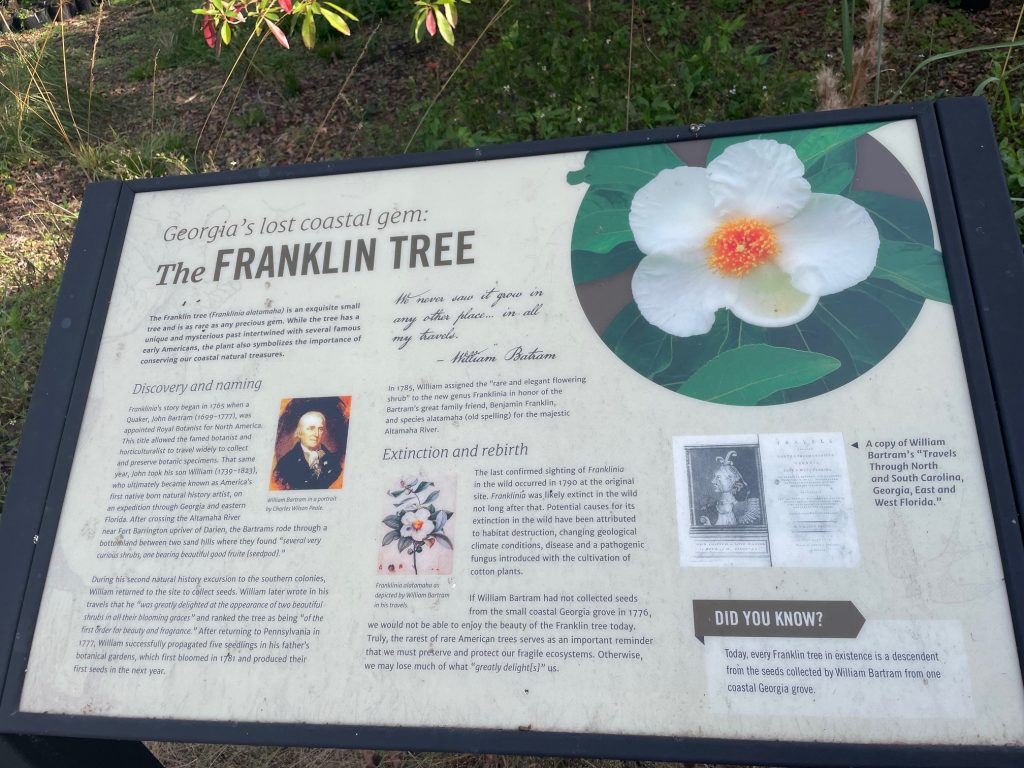

If it were not for their formidable observation skills, at least one species of unique native tree would be completely extinct. While traveling along the Georgia coast in 1765, the Bartrams recorded and named a species of small tree they’d never seen anywhere before. They christened it the “Franklin tree” for their friend and compatriot Benjamin Franklin. Known scientifically as Franklinia alatamaha (after Franklin and the nearby Altamaha River), its similarity to the loblolly bay tree landed it in the Gordonia genus for a while. References in the literature to this tree may include Gordonia alatamaha, Gordonia pubescens var. subglabra, or Lacathea florida, although it is now officially Franklinia alatamaha and considered part of the tea tree family.

William Bartram knew this species was unique, as he never saw the tree elsewhere in any of his extensive travels. He returned to the area in 1776, this time collecting seeds from the Franklin trees and propagating five of them successfully back at his home in Pennsylvania. The last time this species was seen in the wild was at the original wetland floodplain along the Altamaha River between 1790-1803. Now, the only Franklin trees in existence are all descendants of the seeds collected by William Bartram.

Their exact cause of extinction is not clear, but there are some solid theories. Land adjacent to the river was cleared for cotton farms, and the Franklin trees were vulnerable to a fungal pathogen that affects cotton. Based on the early records, the very small endemic population was particularly susceptible to habitat destruction and changing climatic conditions.

While no longer growing in the wild, the tree is mostly living in demonstration gardens and Arboretums on the east coast. However, it can be found in the nursery trade and grown in a large swath of the country if cared for properly. I was introduced to this species for the first time at the Brunswick, Georgia marine extension office. In addition to working with fishermen, they also educate residents on native landscaping and ways to prevent stormwater runoff and pollution. Over a span of a few years, they transformed the “front yard” of their office building from a turf lawn with a couple of oaks to a lush landscape full of flowers, shrubs, and pollinator insects. Included is a Franklin tree, with signage explaining its unique history. At about 15-20 feet tall, it has reached mature height. The original site of the Bartrams’ discovery is less than 20 miles from the garden location.

- The Praying Mantis - June 20, 2025

- Bluebirds in Florida - May 8, 2025

- The Brahminy Blind Snake - April 10, 2025