by Carrie Stevenson | Feb 26, 2019

Compost bins can be built or purchased and provide an easy means of recycling food and yard waste into valuable soil for a garden. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF/ IFAS Extension

What better New Year’s resolution could there be than to start recycling and do our part to preserve our natural resources? By composting yard and kitchen waste, we can also get a jump-start on our spring gardening by creating your own mulch and fertilizer. Done properly, raw compost material can transform into nutrient-rich soil in just six weeks! A free source of “slow release” nutrients, compost also loosens tight, compacted soils and helps our often-sandy soils hold nutrients.

So what is compost? Essentially, it is what’s left of organic matter after it’s been thoroughly decomposed by microbes. Among the common compostable organic materials are leaves, grass clippings, twigs, pine straw, and vegetable/fruit peelings and coffee grounds. When using these items, alternate by using brown (leaves, straw) and green materials (grass clippings, vegetables) in the compost bin to provide adequate carbon and nitrogen. Table scraps containing meat, eggs or oils are not recommended because they can draw rodents and cause an odor. Eggshells are OK, but in general, use only kitchen scraps that are either plants or paper.

The organisms doing the actual composting are microscopic bacteria and fungi, along with earthworms. The microbes need water, oxygen and nutrients to thrive. Rainfall will provide most of the needed moisture, although you may need to hand water the pile on during dry times. For the best results, keep the pile moist but not soggy; if you pick up a handful it should not crumble away nor drip water when squeezed.

To move oxygen through the pile, increasing decomposition and preventing odors, turn the pile on a regular basis with a pitchfork or rake. Some companies sell compost bins in moving cylinders that can be turned with a handle. The process of decomposition will generate extreme heat (over 150°F in the summer) within the pile, which can kill weed seeds and disease-causing organisms.

Done correctly, composting does not smell bad, is very easy to do, and is a great way to do something good for the planet, your yard, and your wallet! Learn more about composting at this University of Florida Extension article.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 7, 2019

The Chickasaw plum is covered in beautiful small white flowers in the spring. Photo credit: UF IFAS

The native Chickasaw plum is a beautiful smaller tree (12-20 ft mature height) that is perfect for front yards, small areas, and streetscapes. True to its name, the Chickasaw plum was historically an important food source to Native American tribes in the southeast, who cultivated the trees in settlements well before the arrival of Europeans. They typically harvested and then dried the fruit to preserve it. Botanist-explorer William Bartram noted the species during his travels through the southeast in the 1700’s. He rarely saw it in the forests, and hypothesized that it was brought over from west of the Mississippi River.

One of the first trees to bloom each spring, the Chickasaw plum’s white, fragrant flowers and delicious red fruit make it charmingly aesthetic and appealing to humans and wildlife alike. The plums taste great eaten fresh from the tree but can be processed into jelly or wine. Chickasaw plums serve as host plants for the red-spotted purple butterfly, and their fruit make them popular with other wildlife. These trees are fast growers and typically multi-trunked.

Almost any landscape works for the Chickasaw plum, as it can grow in full sun, partial sun, or partial shade, and tolerates a wide variety of soil types. The species is very drought tolerant and performs well in sandy soils.

The plum is in the rose family and has thorns, so it is wise to be aware of these if young children might play near the tree.

Winter is ideal tree-planting time in Florida. While national Arbor Day is in spring, Florida’s Arbor Day is the 3rd Friday of January due to our milder winters. This year, Escambia County’s tree giveaway will include Chickasaw plums, so if this tree sounds like a great addition to your landscape, come visit us on January 19 and pick one up.

For more information about tree selection in northwest Florida, contact your local county Extension office.

by Carrie Stevenson | Sep 18, 2018

This tomato hornworm is being parasitized by beneficial wasps. Photo credit: Henry Crenshaw

Why would anyone allow dozens of wasps to thrive in their garden? Why would they let caterpillars keep moving through their pepper bushes? Don’t they know you can spray for that?

As Extension agents, one of the tenets we “preach” in gardening is the concept of Integrated Pest Management (IPM). This technique involves a series of insect control measures that begin with the “least toxic” method of control, using chemicals as a last resort. One of those least toxic measures is “biological control”, in which a natural predator or parasite is recognized and allowed to remove a pest insect naturally. It is important to be able to recognize some of the more common garden predators and parasites. Many times these insects look strange or dangerous, and they are mistaken for pests and killed.

One such beneficial insect to the home gardener is the braconid wasp (Cotesia congregatus). Most people shudder at the mention of wasps, but these tiny (1/8 inch long), mostly transparent wasps are of no danger to humans. Quite the opposite–they are an excellent addition to gardens, especially if you are growing tomatoes or peppers. One of the major pests to these favorite vegetables is the tomato hornworm (Manduca quinquemaculata), a fat green and white-striped caterpillar.

The beneficial wasp can control hornworms because females lay eggs under the caterpillar’s skin, after which the eggs hatch and larvae feed on the hornworm. After eating through the caterpillar, they form dozens of tiny white cocoons on the caterpillar’s skin. The tomato hornworm is rendered weak and near death, and the vegetable crop is saved.

If you happen to find a tomato hornworm covered in these small oval cocoons, consider yourself lucky. Let the process continue, allowing the new generation of beneficial wasps to hatch and continue their life cycle. They will control any future hornworms in your garden, and the whole process is fascinating to watch!

For questions on integrated pest management, beneficial insects, or growing peppers and tomatoes, call your local County Extension office.

by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 10, 2018

A Florida Master Naturalist Uplands class visits the highest point in Florida, located in Walton County. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

For many Floridians, gardening is a window into learning the cycles of the natural world. Understanding pollination, distinguishing beneficial insects from harmful ones, creating compost, or knowing what time of year to apply iron supplements are important for a gardener to be successful. While we have our share of campers, hikers, and kayakers, over the years Extension agents have found that some of our best Master Naturalist students are those with fond memories of farming or gardening as children or adults.

If you have always been fascinated by the natural world and how plants, animals, and people interact, you might be a perfect candidate for the Master Naturalist program. Offered periodically in almost every county in Florida, this adult educational course combines classroom sessions with field instruction, typically over a six-week period. At graduation, students present an original project, which may vary from creating an exhibit, a children’s book, or even an environmental non-profit organization.

Master Naturalist students vary in backgrounds from retired military and teachers to park rangers and college students. Many Master Gardeners find the courses a helpful addition to their training, and utilize their newly gained knowledge when working with clientele. At completion, students receive an official Florida Master Naturalist certificate, pin, and patch.

The traditional 40-hour courses cover Upland, Coastal, and Freshwater Wetland habitats, while the newer “special topics” cover Conservation Science, Environmental Interpretation, Habitat Evaluation, and Wildlife Monitoring. A new “restoration” series has begun with the Coastal Restoration class, which kicked off in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties and is currently being taught in Bay. Extension agents will be offering several classes in the Panhandle this fall—check out the FMNP registration site to see when a class will be offered near you!

by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 2, 2018

The UF / IFAS Entomology and Nematology department has just published this excellent article on Crapemyrtle bark scale.

This pest has made a home in numerous counties scattered throughout the southeastern U.S. and has a moderate to high probability of becoming a problem in Florida. Follow the link above to learn more about this probable pest.

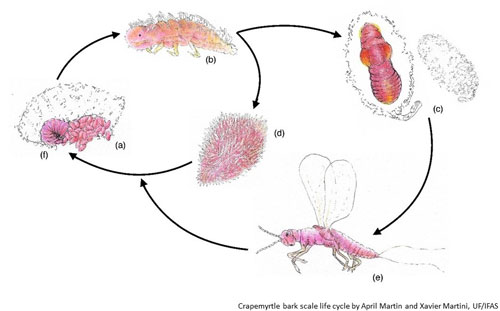

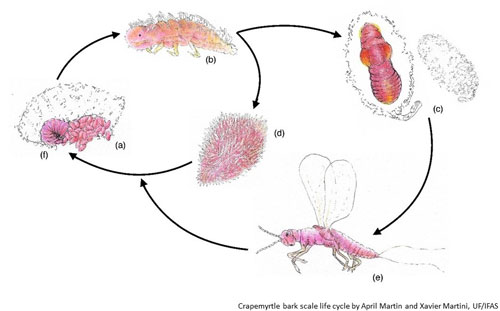

Life cycle of the crapemyrtle bark scale. Nymphs that hatch from the eggs (a) are highly mobile and are called “crawlers” (b). Some nymphs form a white sac and develop into prepupa (c) and then to pupa further inside, before becoming an alate male (e). The females (d-f) do not enter the pre-pupal stage, and start producing eggs following mating with the male. Life cycle by April Martin and Xavier Martini, University of Florida.