by Carrie Stevenson | Sep 8, 2017

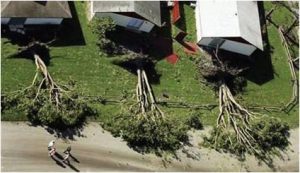

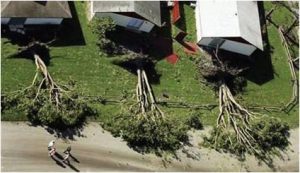

Trees are often among the first victims of hurricane-force winds. Photo credit: Mary Duryea, University of Florida.

Well, it is the peak of hurricane season (June 1-November 30), and this one is proving to be no joke. After having all summer to heat up, Gulf and Atlantic water temperatures peak in late August-mid September, feeding storms’ strength. Legendary hurricanes like Harvey, Katrina, and Andrew all made landfall during this time of year. The models for Irma show likely impacts in Florida, and due to its extreme size, most of the state is in line to endure heavy rain and wind regardless of location.

From a landscaping perspective, hurricanes can be truly disastrous. I will never forget returning home after evacuating from Hurricane Ivan and realizing all the leaves had been blown from nearly every tree in town. Mid-September suddenly looked like the dead of winter. A Category 3 storm when it landed near the southwest corner of Escambia County, Ivan was responsible for a 40% loss of tree canopy in our county.

Even if the Panhandle is not directly impacted by a storm, it is always smart to prepare. Research conducted by University of Florida arborists and horticultural specialists have yielded some practical suggestions.

To evaluate trees for potential hazards;

- Know your tree species and whether they are prone to decay or wind damage (more below).

- Look for root or branch rot—usually indicated by very dark spots on the bark.

- Tree structure—is there a single, dominant central trunk? Are branches attached to the trunk in a U-shape (strong) or V-shape (weak)?

- Smart pruning—never “top” (cut the tops from trees) but instead prune crowded limbs and remove limbs that are dead, dying, or hanging above power lines.

As for species selection, keep in mind that pines generally do not perform well in gale-force winds. Longleaf pines are quite strong, but common slash pines often snap or lean in storms. Even if a pine tree survives, it can be vulnerable to damage or death from pine bark beetles. It is wise to monitor pines for up to 2 years after a storm.

In addition, a survey conducted throughout the southeastern United States after hurricanes from 1992-2005 yielded important information on the most (and least) wind-resistant tree species. Live oaks and Southern magnolias topped the list, while pecans and cherry laurels performed poorly. This full, user-friendly report from the study is a useful tool.

For more hurricane preparedness information, visit the UF IFAS Extension Disaster Manual online or contact your local Extension office or Emergency Management agency.

by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 11, 2017

The passionflower vine is beautiful and attracts butterflies, but can also be used for food and sedation drugs. Photo credit: Dorothy Birch

Ethnobotany lies at the intersection of culture, medicine, and mythology. The “witch doctors” and voodoo practitioners, the followers of the Afro-Cuban religion of Santeria, and the wise elders of ancient Chinese civilizations are all ethnobotanists. So, too, are the modern day field biologists who discover and develop medicinal plants into an estimated half of our pharmaceutical drugs. Simply put, ethnobotany is the study of how people and cultures (ethno) interact with plants (botany).

For tens of thousands of years, humans have been learning about plants’ chemical, nutritious, and even poisonous properties. Plants evolve these properties to defend themselves against pathogens, fungi, animals and other plants. Other properties, like color, scent, or sugar content may attract beneficial species. Humans most likely started paying attention to plant characteristics to decide whether to eat them. From there, one can imagine people started using plants to build structures or use fiber for ropes, baskets, and clothing.

My first experience with the idea of ethnobotany was as a college student on a study tour of Belize. A professional ethnobotanist took us on a tour of the Maya Rainforest Medicine Trail, pointing out dozens of native trees, shrubs, and grasses used for medicinal and cultural purposes by local tribes. From birth control and pain relief to chewing gum and pesticides, the forest provided nearly everything Central American civilizations needed to survive for thousands of years and into the present. The tour captured my imagination as I considered the possibilities yet undiscovered in the deep rainforests worldwide.

Of course, there is no need to travel out of the country, or even the state, to learn about useful native plants. One of my favorite publications put out by UF IFAS Extension specialists is “50 Common Native Plants Important in Florida’s Ethnobotanical History.” Another fascinating source of information about historic, cultural, and even murderous uses of plants is Amy Stewart’s Wicked Plants: The Weed That Killed Lincoln’s Mother and Other Botanical Atrocities. Plants with interesting historical uses make for great stories along a trail, and help create a connection between the casual observer and the natural world around them.

A handful of interesting native plants with significant medicinal properties include the cancer-fighting plants saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) and mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum). Saw palmetto berries are used for prostate cancer treatment, while the $350+ million annual Florida mayapple harvest helps produce chemotherapy drugs for several types of cancer. The carnivorous bog plant, pink sundew (Drosera capaillaris) uses enzymes to break down insect protein, and Native American tribes used the plant for bacterial and fungal skin disorders.

Sundews, tiny carnivorous plants found in pitcher plant bogs, use an enzyme to dissolve insect proteins. Native Americans recognized this property and used the plant for skin maladies. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Many plants had (and still have) multiple uses. Yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) leaves brewed as a highly caffeinated tea were used ceremonially and before warfare by many southeastern American Indian tribes, and then later by early American settlers when tea was difficult to import. Holly branches were used for arrows, and the bark for warding off nightmares. The purple passionflower, or maypop (Passiflora incarnata) vine attracts butterflies and produces a pulp used for syrups, jams, and drinks. Passionflower extract has also been developed into dozens of drugs and supplements for sedation.

Early civilizations living closer to the land knew many secrets that modern medicine has yet to unlock. Thanks to the ethnobotanists, the field and forest will continue to heal and provide for us for many generations yet to come.

CAUTION: Many of the plants listed or referenced can have hazardous or poisonous properties without appropriate preparation or dosage. Allergic reactions and prescribed drug interactions may occur, and many unproven rumors exist about medicinal uses of plants. Always consult a physician or health professional before trying supplements.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 5, 2017

This rain garden used stone for a berm and muhly grass as a decorative and functional plant. Photo credit, Jerry Patee

Tropical Storm Cindy’s early arrival soaked northwest Florida this month, followed by even more heavy rain. Homes in low areas and along the rivers flooded and suffered extensive damage. That being said, we are just entering our summer “rainy season,” so it may be wise to spend extra time thinking about adjusting your landscape to handle our typically heavy annual rainfall.

For example, if you have an area in your yard where water always runs after a storm (even a mild one) and washes out your property, you may want to consider a rain garden for that spot. Rain gardens are designed to temporarily hold rainwater and allow it to soak into the ground. However, they are quite different aesthetically from stormwater ponds, because they are planted with water-tolerant trees, shrubs, groundcovers and flowers to provide an attractive alternative to the eroding gully that once inhabited the area! Rain gardens are not “created wetlands,” but landscaped beds that can handle both wet and drier conditions. Many of the plants best suited for rain gardens are also attractive to wildlife, adding another element of beauty to the landscape.

A perfect spot for a rain garden might be downhill from a rain gutter, an area notorious for excess water and erosion. To build a rain garden, the rainwater leaving a particular part of the property (or rooftop), is directed into a gently sloping, 4”-8” deep depression in the ground, the back and sides of which are supported by a berm of earth. The rain garden serves as a catch basin for the water and is usually shaped like a semi-circle. The width of the rain garden depends on the slope and particular site conditions in each yard. Within the area, native plants are placed into loose, sandy soil and mulched. Care should be taken to prevent the garden from having a very deep end where water pools, rather allowing water to spread evenly throughout the basin.

This larger rain garden, or bioretention area, functions as stormwater treatment for a large parking lot in North Carolina. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF / IFAS Extension

Besides reducing a problematic area of the lawn, a rain garden can play an important role in improving water quality. With increasing populations come more pavement, roads, and rooftops, which do almost nothing to absorb or treat stormwater, contributing to the problem. Vegetation and soil do a much better job at handling stormwater. Excess sediment, which can fill in streams and bays, and chemicals from fertilizers and pesticides are just some of the pollutants treated within a rain garden via the natural growth processes of the plants.

A handful of well-known plants that work great in rain gardens include: Louisiana iris, cinnamon fern, buttonbush, Virginia willow, black-eyed Susan, swamp lily, tulip poplar, oakleaf hydrangea, wax myrtle, Florida azalea, river birch, holly, and Southern magnolia. For a complete list of rain garden plants appropriate for our area, visit the “Rain Garden” section of Tallahassee’s “Think about Personal Pollution” website.

For design specifications on building a rain garden, visit the UF Green Building site or contact your local UF IFAS County Extension office.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 15, 2017

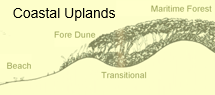

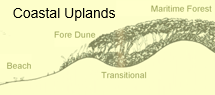

Salt shear and onshore breezes often cause coastal maritime forests to grow at a slant away from the coast. Credit: Florida Master Naturalist Program

People from other parts of the country often move into Florida with expectations of their landscape beyond its capabilities. Those gorgeous peonies that grew up north or the perfect tomatoes they grew in California seem to wither in the heat or succumb to any number of insect or fungal pests. Adapting to our conditions takes listening to those with more experience, changing old habits or varieties and definitely adjusting expectations. Once you understand what the north Florida climate requires, you might be pleasantly surprised with a bumper crop of lemons or a thriving hibiscus that would never have worked in Michigan.

The same idea applies to landscaping on the beach or near areas of saltwater. Particularly on barrier islands like Perdido Key, Santa Rosa Island, and the coastal islands around Apalachicola, the influence of salt spray and hot, dry, sandy soils cannot be underestimated. If you have ever looked closely at the shape of the mature oak trees on the back sides of sand dunes, you’ll notice they’re shorter and tend to lean and grow away from the beach. This is due partially to the onshore breeze that steadily blows off the water, but also due to a phenomenon called salt shear. Salt shear occurs in areas where breaking waves release salt, which evaporates from water droplets and blows into the landscape. Unless specifically adapted to living in a saline environment, the salt can halt growth of the plants receiving the bulk of the spray. Many plants adapt to this by sealing up any vulnerable growing tips and sending energy for growth to the other side, resulting in a sloped shape. Land further inland from the Gulf will have consecutively less salt spray to endure.

Keep in mind that the soil on a barrier island is highly porous; it does not hold water nor nutrients well. The best option is to look at what grows there naturally, and select some of the most attractive and hardy choices for a home or commercial landscape. Knowing that a residence or commercial business is located within these environmental conditions, the best way to ensure success is to work with your surroundings instead of against them.

Below are a handful salt-tolerant options to consider.

Beach sunflower (Helianthus debilis): The yellow-blooming beach or dune sunflower will reseed and spread along as a hardy groundcover.

Muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris): Muhly grass is a native clumping grass commonly used in Florida landscapes. It has showy pinkish-purple blooms in mid-fall.

Beach cordgrass (Spartina patens): Beach cordgrass is a native grass that serves as a sand stabilizer. While not particularly showy, it can serve as a good foundation plant.

Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens): These evergreen shrubs are extraordinarily hearty and long-lived. They produce a fruit that is an important food source for wildlife.

False rosemary (Conradina canescens): This evergreen shrub blooms purple, attracts wildlife, and is a hardy native species.

Firebush (Hamelia patens): Firebush has long-lasting red blooms that attract hummingbirds and native butterflies.

Blanketflower (Gaillardia pulchella): These colorful wildflowers attract pollinators like bees and butterflies and are extremely drought and salt tolerant.

Sunshine mimosa (Mimosa strigillosa): This ground-running plant has colorful, spherical pink blooms and attracts bees. The delicate leaves of the plant are sensitive to touch, and will fold up when touched.

For more information on salt-tolerant coastal plants and trees in our area along with cold-tolerant palms, contact your local Extension agent or Native Plant Society.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 1, 2017

The Southeastern blueberry bee uses buzz pollination on a blueberry plant. Photo credit: Tyler Jones, UF IFAS.

This time of year, blueberry bushes are flowering and small fruit are coming onto the wild and cultivated bushes in north Florida. Many of us, myself included, look forward to the late-spring harvest of blueberries, taking our children out to u-pick operations and digging out family recipes for blueberry-filled desserts.

What many do not know, however, is that there’s a specialized bee that literally lives for this season. During the last few weeks, this little insect has been furiously pollinating blueberry bushes during its short, single-purpose lifetime.

The Southeastern blueberry bee, Habropoda labriosa is active only in mid-March to April when blueberry plants are in flower. They are smaller than bumblebees, and the yellow patches on their heads can differentiate males. Blueberry pollen is heavy and sticky, so it is not blown by the wind, and the flower anatomy is such that pollen from the male anther will not just fall onto the female stigma. Blueberry bees must instead attach themselves to the flower and rapidly vibrate their flight muscles, shaking the pollen out. Moving to the next flower, the bee’s vibrations will drop pollen from the first flower onto the next one. This phenomenon is called “sonicating” or ‘buzz pollination” and is the most effective method of creating a prolific blueberry crop.

Blueberry bees do not form hives, but create solitary nests in open, sunny, high ground. Females will dig a tunnel with a brood chamber large enough for one larva, filling it with nectar and pollen. After laying an egg, the female seals the chamber and the next generation is ready. The species produces only one generation of adults per year.

By the time we are picking fresh blueberries next month, you probably won’t see any blueberry bees around. However, we should all consider these insects’ short-lived but vitally important role in Florida’s $82 million/year blueberry industry!

For more information, check out the beautifully illustrated USDA Forest Service publication, “Bee Basics—An Introduction to our Native Bees,” or North Carolina State University’s entomology website.