by Danielle S. Williams | Jun 5, 2025

Blackberries grown in North Florida. Photo credit: Dr. Shahid Iqbal

Blackberries are a deciduous crop that thrive in temperate climates. While several native blackberry species grow wild in Florida, their small fruit size, late maturation, and low yields make them unsuitable for commercial production. Historically, cultivated blackberry varieties in Florida, have been primarily limited to homeowner production, but, UF/IFAS researchers are working to change that. Through the development of improved cultivars with higher yields, better flavor, and little to no chilling hour requirements, blackberries are becoming a more viable option for commercial and small-scale growers in North Florida.

UF/IFAS invites you to learn more about blackberries and the current research associated with blackberry production at the Blackberry Field Day, on Wednesday, June 18th. This event will be held from 8:30 – 11:30AM Eastern Time, at the UF/IFAS North Florida Research & Education Center (NFREC), located at 155 Research Road, Quincy, Florida.

This is a free event aimed at educating home gardeners, farmers, landowners, and industry representatives about production practices such as proper planting, pruning, and fertilization. Attendees will be able to tour the blackberry planting at the UF/IFAS NFREC as well as sample different blackberry varieties! The field day aims to present attendees with the potential benefits, challenges, and current research associated with growing blackberries in North Florida.

Attendees will be able to visit the blackberry planting at UF/IFAS North Florida Research & Education Center in Quincy. Light refreshments will be provided. Space is limited, so please register using the link below or by calling 850-875-7255 to reserve your spot!

by Danielle S. Williams | Apr 21, 2025

If you’ve ever walked barefoot through a patch of burweed, you know this is a very unpleasant experience. Lawn burweed, also called spurweed or stickerweed, is a low growing winter annual that produces hard, spiny burs that contains the plant’s seeds. These burs or stickers make walking on grass extremely painful for not only people walking barefoot, but pets as well.

Lawn Burweed. Photo: Danielle Williams.

Dealing with lawn burweed can be tricky. Because lawn burweed is a winter weed, seeds actually germinate when temperatures are cool in the fall (late October-November). It then remains unseen during the cold months but as temperatures warm up in the spring, lawn burweed initiates a period of rapid growth and forms the spiny burs which may be hard to see but are easily felt. At this stage, the plant has set seed for next year and killing the remaining foliage won’t remove the burs. Moving forward, there are some things to consider.

Cultural Control

Burweed tends to be prominent in high traffic areas or areas where grass is declining so it is important to prevent infestations by maintaining a healthy, dense lawn. This can be achieved by fertilizing and liming according to soil test results as well as mowing at the proper height and frequency for your specific turfgrass. A healthy lawn can outcompete burweed for light, water, and nutrients and reduce the level of burweed infestation. For more information on maintaining your lawn visit: https://hort.ifas.ufl.edu/yourfloridalawn/

If burweed is only in isolated areas, you can always dig it up and dispose of it. Be sure to wear gloves and watch out for the stickers!

Chemical Control

Post-emergent control: Post-emergent herbicides are most effectively applied when burweed plants are young, actively growing, and haven’t set burs yet from December – February. Controlling burweed now is not impossible, but the burs have likely already formed and will remain present even after the weed dies. Additionally, since burweed is a winter annual, it will begin to die as temperatures reach 90 ◦F and above.

Look for herbicides containing the following active ingredients to help with post-emergent control:

- Atrazine – sold under many brand names and safe in centipede, St. Augustine, and bermudagrass. Do not use in zoysiagrass or bahiagrass lawns.

- Dicamba, mecoprop, 2,4-D – commonly sold in three-way formulations through many brand names. Generally safe in centipede, St. Augustine, bermuda, zoysia, and bahiagrass lawns.

- Metsulfuron – sold under several brand names and safe in centipede, St. Augustine, zoysia, and bermudagrass. Do not use in bahiagrass. Be careful if used around ornamentals.

- Thiencarbazone, iodosulfuron, dicamba. Safe in centipedegrass, zoysiagrass, bermudagrass, and St. Augustinegrass. Do not use in bahiagrass.

Pre-emergent control: If you are struggling with a lawn burweed infestation this spring, plan to do a pre-emergent herbicide application this fall. A herbicide containing the active ingredient, isoxaben can be used to control lawn burweed in centipedegrass, St. Augustinegrass, bermudagrass and zoysiagrass. In order for a pre-emergent herbicide application to be effective, it must be applied before the plant sprouts. For burweed, isoxaben can be applied in October or once temperatures fall to 55-60 ◦F and winter weeds begin to germinate.

Of course, before using any type of herbicide, always read the label instructions! If you have questions about lawn burweed control, please contact your local Extension Agent.

For more information, please visit: ENH884/EP141: Weed Management Guide for Florida Lawns

by Danielle S. Williams | Mar 13, 2025

When most people think of insects, they think of the bad ones, but not all insects are bad! Insects are labeled as bad or ‘pests’ when they start causing harm to people or the things we care about such as plants, animals, and buildings but most insects are GOOD! In fact, of the millions of insect species found throughout the world, less than 2% are actually considered pests. There are several different ways insects can be beneficial in your garden or landscape:

- They prey on pest insects. Many species of insects eat pest insects! For example, lady beetles (ladybugs) and lacewings eat pest insects like aphids, mealybugs and whiteflies. They can help keep insect populations in balance. It’s important to recognize some of the beneficial insect species (and their different life cycle stages) that you might find in your garden. The UF/IFAS Extension bookstore has a great identification guide: Helpful, Harmful, Harmless?

- They parasitize pest insects. Some species of good insects live in or on pest insects. For example, parasitoid wasps lay their eggs into pest insects and when the wasp eggs hatch, they feed on the pest species. Here’s a really great video to show the process: Parasitic Wasps – National Geographic

- They pollinate. Many of the good insects like native bees, honeybees, butterflies and moths help us pollinate our gardens. They transfer pollen grains from flower to flower that help plants bear fruit.

- They decompose. Insects also help aerate our soils by breaking down dead material and recycling nutrients. Dung beetles are a great example! They bury and consume dung which improves soil quality.

One of the best things you can do for your garden is learn to differentiate pest insect species from beneficial ones! Just because you see an insect on your plant, doesn’t necessarily mean it is causing harm. If you see an insect, are you seeing injury to the plant? If so, what type of injury (defoliation, yellowing, leaf curling)? If you aren’t seeing injury, then you may not have anything to worry about. If you find something you’re unsure of, you can always reach out to your local UF/IFAS Extension Agent!

Pipevine swallowtail on Azalea.

Attracting and encouraging beneficial insects can really help your garden and landscape thrive. The best way to attract beneficial insects to your garden or landscape is to have lots of plant diversity. A mix of trees, shrubs, annual and perennial flowers in the landscape is best. Trees and shrubs will provide shelter for insects to overwinter, and flowers provide pollen and nectar.

Flowers in the carrot family (Apiaceae) such as caraway, coriander, cilantro, dill and fennel are attractive for parasitic wasps. Flowers in the Aster family (Asteraceae) such as blanketflower, coneflower, coreopsis, cosmos and goldenrod are attractive for larger predators like lady beetles and soldier beetles. These can be incorporated into the garden or flower beds.

For more information on attracting beneficial insects to your landscape, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agent!

by Danielle S. Williams | Jan 24, 2025

During the summer months, we can’t seem to get away from insects. Whether it’s a fly circling your food, those pesky aphids in your garden, or a mosquito out for blood, they make their presence known. But when winter rolls around and temperatures drop, they seem to disappear. But where do they go?

Unlike humans, insects are exothermic or cold blooded. They cannot regulate their own body temperature and must rely on the heat of the environment. Each insect species has its own developmental threshold, a temperature below which no development takes place. For many insects, that threshold is about 50 degrees Fahrenheit. This means that when temperatures drop below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, consecutively, the insect is not active, and no development is occurring. Typically, the warmer the temperature is (as long as it is above the development threshold), the more insect activity we see.

Insects may also enter a state called diapause, which is similar to hibernation. During diapause, an insect’s metabolism slows dramatically, and the insect stops feeding, growing, or reproducing. This allows the insect to survive through cold winter conditions, conserving energy until temperatures warm up again.

Monarch butterfly. Photo credit: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS

Another insect survival technique during the winter is migration. Many species of insects migrate to warmer climates to escape the cold. A well-known example of this is with the infamous Monarch butterfly migration. Monarchs migrate south to Mexico to overwinter and survive the cold weather. Some other insects migrate in smaller, less noticeable ways such as moving to different micro-climates. For example, beetle grubs may move down deep within the leaf litter to stay warm. Insects like lady beetles may congregate in large numbers inside homes, barns, or buildings during the winter.

Some insect species can produce glycerol, a type of anti-freeze, that prevents their body from freezing even when temperatures drop below freezing.

While many insects seem to disappear during the winter, they’re actually using their time wisely and although, cooler temperatures may slow down their activity, they won’t necessarily change insect populations drastically. Insects are well adapted for survival, and they are here to stay. They’re just enjoying a break until the warmth of spring brings them back!

For more information on insects, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office.

by Danielle S. Williams | Dec 5, 2024

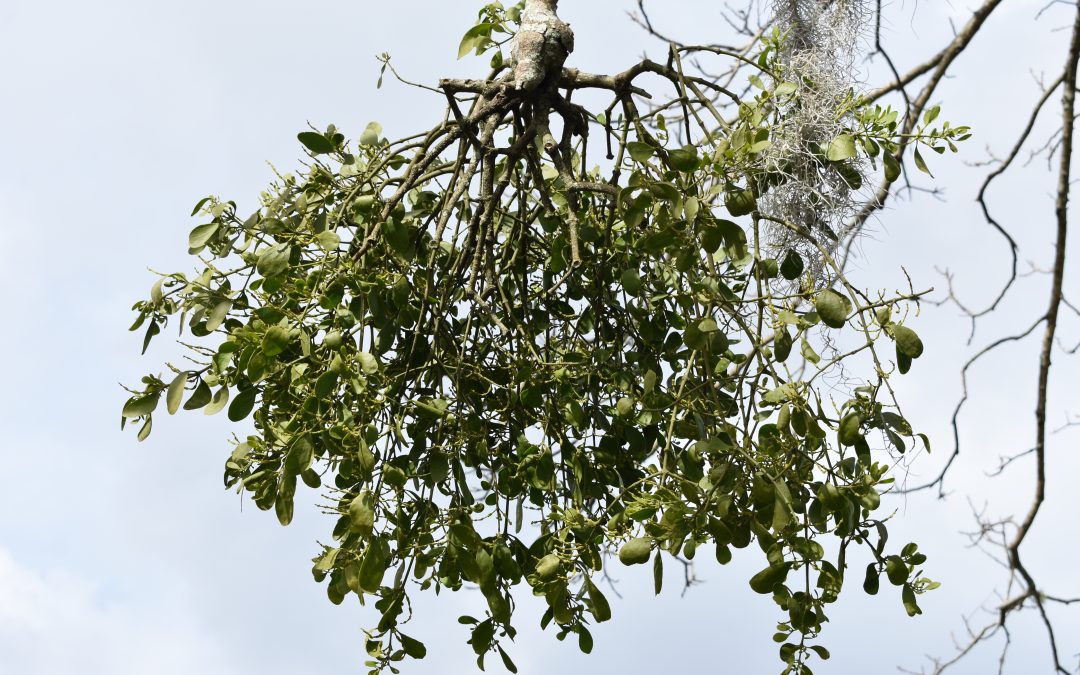

A kiss under the mistletoe…a timeless holiday tradition that we’ve all heard of. If you look around, you’ll be sure to find some growing on the branches of several different species of hardwood trees throughout the Panhandle. This same mistletoe is often harvested and brought inside to add a festive touch to holiday decorations.

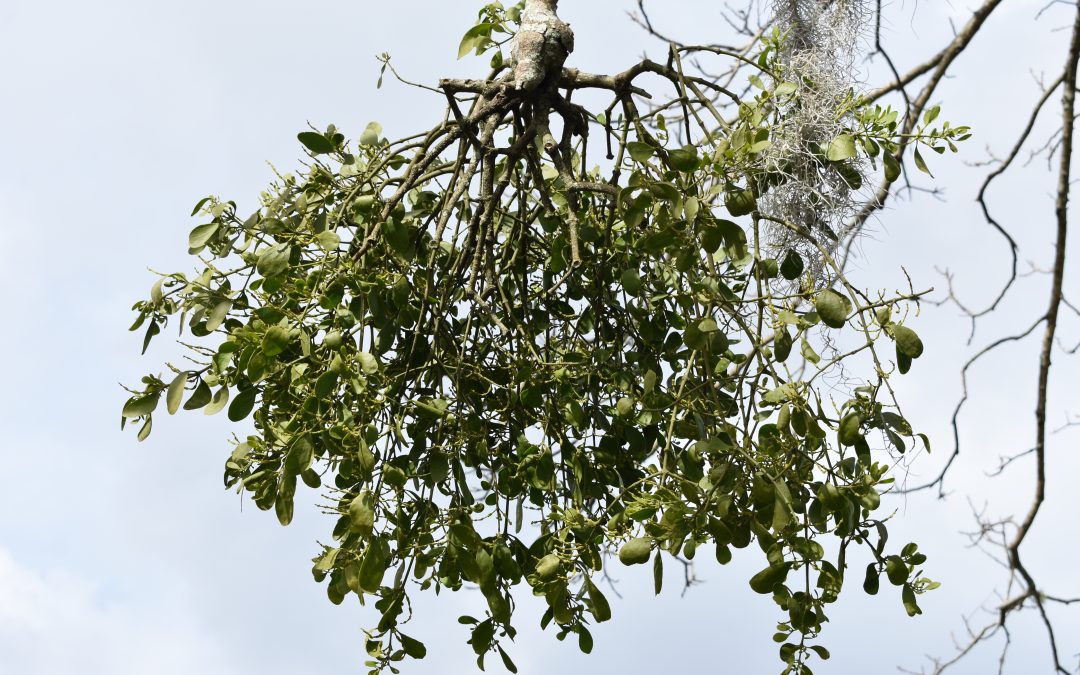

Mistletoe hanging in pecan tree. Photo credit: Danielle Williams.

The species we have here is known as American or oak mistletoe. It only grows in deciduous trees that shed their leaves annually. While mistletoe has over 200 host plants, you’ll find it most commonly in oaks, maples, and pecans. Look for a green, ball shaped mass about 3’ wide in the tops of trees. Each mass is an individual mistletoe plant, and some trees may have a few or many.

Mistletoe. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones.

Mistletoe is a small, evergreen shrub with white berries. It is considered a hemi-parasitic plant because it can produce some of its own food through photosynthesis, but it also relies on its host tree for water and nutrients. Most healthy trees can tolerate mistletoe without suffering any significant harm. However, trees that become severely infested with mistletoe can become weakened and decline in health, especially if the tree is already stressed by pests, drought or disease.

Pecan Tree Infested with Mistletoe. Photo credit: Danielle Williams.

If you have mistletoe growing on trees in your yard, the best way to support the trees is to maintain their overall health through proper watering, fertilization and pest management. If you suspect trees on your property are suffering from mistletoe, you can prune the infected branches. Since mistletoe roots from its host tree, simply cutting it flush with the branch will not kill it. You can remove the roots by pruning at least six inches below the point of attachment.

While some may consider mistletoe to be a nuisance, it does provide ecological benefits. Mistletoe serves as a valuable resource to our wildlife, primarily birds and insects. Oak mistletoe is the only food source for the larvae of the great purple hairstreak butterfly.

If you are considering harvesting mistletoe this winter to use for decoration, be sure to place it carefully. Mistletoe berries and all parts of the plant are poisonous to humans so keep plants and decorations out of the reach of children and pets. For more information on mistletoe, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office.