by Gary Knox | Apr 7, 2022

Written by: Kelly Thomas – Agricultural/Food Scientist II with the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center

Written by: Kelly Thomas – Agricultural/Food Scientist II with the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center

Imagine walking out your front door with a cup of coffee to admire your garden. A cucumber vine, ripe with crisp, succulent fruit, has grown so large and sprawling that the white staircase handrail is serving as its trellis. The resulting appearance is a lush green entranceway to the front door. The wall of cucumber leaves stands tall behind burgundy-colored day lilies and stokes asters that are shockingly blue. Nearby, buzzing bees feed on fragrant basil flowers. The plum tree planted near the road is heavy with perfectly round reddish-purple fruit that is almost ready to harvest.

Foxtail rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) standing tall in the Dry Garden. Photo Credit: Kelly Thomas – University of Florida/IFAS

You’ve taken up foodscaping, the concept of integrating ornamental plants and edible plants within a traditional landscape. It began during the pandemic with more time spent at home, and the desire to tend to the growth of something. Now, the garden’s bounty has provided groceries, which has proven doubly beneficial as the pandemic continues to disrupt the supply chain and drive up the cost of food.

Brie Arthur sitting on steps next to tomato vines. Photo Credit: Brie Arthur

The concept of foodscaping is not new. In fact, foodscaping has been around in some form or fashion for centuries. In the early 2000’s, Sydney Park Brown, now a UF/IFAS emeritus associate professor, published an EDIS document titled ‘Edible Landscaping.’ Brown describes how edible landscaping allows people to create a multi-functional landscape that increases food security, reduces food costs, and provides fun and exercise for the family, along with other benefits. Foodscaping, another term for edible landscaping, really took off as a movement during the 2008 economic recession.

Around that time, a horticulturist named Brie Arthur wanted to grow vegetables to save money on groceries. However, the restrictions placed by her H.O.A. forced her to venture away from a standard vegetable garden. Within six months, Arthur had won ‘Yard of the Year,’ proving that edible plants can also be aesthetically pleasing, especially when incorporated into a landscape design. Now, her one-acre lot in North Carolina provides almost 70% of what she and her husband consume. Her garden produces food year-round, everything from sweet potatoes, garlic, and pumpkins to edible flowers like dahlias. She even grows sesame and barley, or as she calls it, “future-beer.”

Utrecht blue wheat beginning to form seed heads. Photo Credit: Kelly Thomas – University of Florida/IFAS

Brie Arthur is a charismatic speaker and bestselling author. She continues to be a major proponent of the foodscape movement, inspiring others to realize their landscape’s full potential. Arthur came and gave an energetic and action-packed presentation on foodscaping at UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) in Quincy, FL on March 5th, 2022. Before the workshop, which was titled ‘A New Era in Foodscaping’ adjourned, participants toured edible displays in Gardens of the Big Bend (GBB), a botanical garden located at the UF/IFAS NFREC. Tour participants walked by golden and red-colored amaranth plants bordered by carrots in the Discovery Garden. Waist-high rosemary plants held their own next to agaves and other desert giants in the Dry Garden.

For more information and advice on foodscaping, check out Brie’s YouTube channel, Brie the Plant Lady. Photos of her garden in North Carolina can be found on her blog. University of Florida resources on edible landscaping/foodscaping can be found via EDIS. And come visit Gardens of the Big Bend in Quincy to view edible garden displays in person!

by Gary Knox | Dec 15, 2021

Bromeliads are a type of succulent that are valued for bold foliage and colorful, exotic and long lasting flowers. Members of the bromeliad family (Bromeliaceae) originate in the tropical Americas in habitats ranging from rain forests to deserts. Bromeliad species are very diverse and include tree-dwellers like Spanish Moss as well as terrestrial plants like Pineapple.

Most colorful bromeliads are not winter hardy in the Florida Panhandle. However, two bromeliads in particular are cold hardy, vigorous, and provide colorful, exotic flowers in fall and winter in North Florida: Matchstick Bromeliad and Queen’s Tears. These two are easy to grow, tough, low maintenance plants and are fondly regarded as passalong plants here in North Florida.

Matchstick Bromeliad (image by K. Thomas)

Matchstick Bromeliad

The genus Aechmea contains many cold hardy bromeliads of which the most widely available is the Matchstick Bromeliad, Aechmea gamosepala. This small-growing Aechmea forms rosettes of nearly-spineless, stiff, medium green leaves about 8 inches tall and wide. Each tightly clustered rosette of foliage forms a “tank” which holds water for the plant to absorb during dry weather. In late Fall and Winter, each rosette can produce a colorful scape of flowers held just above the foliage. Long, narrow flowers are attached up and down the spike and are pink/purple with blue tips, looking somewhat like psychedelic matchsticks. This bromeliad is one of the most cold hardy, tolerating temperatures as low as 20°F for short periods. Best of all, Matchstick Bromeliad quickly forms offsets of foliage rosettes that are easily separated, planted and shared.

Queen’s Tears (image by G. Knox)

Queen’s Tears

The genus Billbergia also contains many cold hardy bromeliads and one of the most popular is Queen’s Tears, Billbergia nutans. Queen’s Tears blooms in mid-winter with arching stems bearing bright pink bracts and tipped with fantastic dangling flowers of green petals edged in blue around a long column of yellow stamens. Allegedly, the beautiful flowers drip nectar when disturbed, thus providing the common name of Queen’s Tears. This bromeliad consists of slender, grey-green, leathery foliage that forms long, narrow rosettes 10 to 18 inches tall, giving the plant a graceful and arching habit. Truly one of the most cold hardy bromeliads, Billbergia nutans reportedly tolerates temperatures in the low teens, making it hardy in USDA Hardiness Zone 8a. Plants of Queen’s Tears grow quickly and form numerous offsets that can rapidly fill a pot to the point of almost bursting. This quality makes it easy to separate clumps to share with all your friends and family, and giving the plant its other common name of “friendship plant”.

Some other Billbergia species are almost as hardy, and some of these feature spotted or variegated leaves. Other bromeliads with good cold hardiness are Dyckia, Neoregelia and Vriesea species.

Care and Culture

Bromeliads are easy to grow and often tolerate some neglect. Most are adapted from part sun through shade, and are tolerant of drought and low moisture conditions. Bromeliads grow best in containers or well-drained soils but also may be mounted on boards, fences, trees or palm trunks. Most have limited root systems because their foliage rosettes form a “cup” that collects, holds and absorbs water as well as debris that breaks down into nutrients for the plant. Bromeliads have low nutrient requirements but will grow faster with light applications of fertilizer (to the roots, not in the foliage tanks). Though these two bromeliads are cold hardy down to 20°F, it’s best to grow them in protected areas so as to avoid damage from freezes that are colder than expected.

For more information:

Bromeliads at a Glance: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep337

Bromeliad Society International: BSI | Bromeliad Society International

by Gary Knox | Sep 2, 2021

‘Stellar Ruby’ is a new purple-flowered hybrid banana-shrub that will soon be released nationally

You just learned about a fabulous new plant, and you HAVE to have it. How can you acquire this rare treasure?

Many of us gardeners have experienced this desire for a “new” plant but have quickly become frustrated with trying to locate and buy that particular plant. It’s not easy, or else that plant wouldn’t be new or rare, but the four P’s outline a few strategies for satisfying a “new” plant passion: plant societies, plant institutions, patience and payment.

Plant societies are one of the best avenues for acquiring new plants. Most plant societies consist of members with intense interest in particular plants or plant groups, so find the society that supports the plant that interests you. Plant society members often include breeders or plant explorers who introduce new plants. Whether magnolia or camellia or conifers or other plants, membership in such societies can give you a leg up on learning about, seeing, and accessing new plants. Consequently, fellow society members are often the first to acquire the newest plants, and that could be you!

Beyond this, participation in generalist plant groups can also give you unexpected benefits of networking with like-minded people. Thus, don’t overlook groups like Master Gardeners, garden clubs, or garden/park support groups. Their members often include passionate plant people like you who may have more connections (or special plants) than you realize.

Similarly, plant institutions such as universities or botanic gardens are another way to learn about and acquire new plants. These institutions often hold plant sales or fund-raising plant auctions that include new, unusual or rare plants. Online plant sales or auctions are becoming more common, so distance is less of an obstacle than it used to be. However, these institutions are less focused on particular plants, so it may be hit-or-miss to find that particular plant you want. To increase the chances of finding your desired plant, contact these institutions and ask to be notified about these events. You may even find a plant you didn’t know you wanted!

Patience is a virtue when trying to acquire new plants. Some plants take a long time to propagate or are not easy to propagate or grow. If you have the patience to wait, many plants will become more available – – – and at a more reasonable cost – – – as nursery production catches up to demand.

Finally, “payment”: let’s face it, money talks! If you have the funds, you can usually find the means to acquire the plants you desire. Most new or rare plants usually enter the market through specialty nurseries, operations that often maintain their own breeding or plant exploration programs or have exclusive arrangements with those who do. This is an expensive means of obtaining new plants, and therefore these specialty nurseries rightly charge more for their plants.

Another way money works to your advantage is the ability to travel. Many specialty nurseries, collectors, etc. often aren’t found in our part of Florida. If you can travel to these nurseries, botanic gardens, etc., it will be much easier to acquire unusual plants. If you can’t afford special trips to these sites, consider taking vacations to areas near these specialty nurseries, or to areas where these specialty nurseries are “on the way” to your vacation destination.

It goes without saying that you should learn about a “new” plant as much as possible before investing in an extensive hunt. Simple internet searches should tell you if that plant will be adapted to the climate and soil of your garden. At the other extreme, check resources like the IFAS Assessment (https://assessment.ifas.ufl.edu/) to make sure that particular plant won’t become invasive in your region of Florida.

Gardening is a very fulfilling activity, and the excitement of “new” plants just makes gardening more fun! Happy hunting!

by Gary Knox | Jun 17, 2021

‘Disney’ scarlet ginger lily produces beautiful orange flower clusters atop stems growing up to 7 feet in height

If you’re looking for colorful flowers with superpowered fragrance, look no farther than ginger lily (Hedychium sp.). This group of plants packs a punch with big, bright flowers, intoxicating fragrance and bold tropical foliage, all in a robust herbaceous perennial that is perfectly hardy in north Florida.

Ginger lilies are tropical and subtropical plants in the Zingiberaceae (Ginger) Family. They produce fragrant, colorful, complex flowers and often other plant parts also are aromatic. Ginger lily flowers appear in racemes or spikes at the tops of cane-like stems 4 to 6 feet or more in height. Flowering summer until frost, the clumps of upright stems grow from thick rhizomes that creep underground just below the soil surface. Native to Asia and related to the spice, true ginger (Zingiber officinale), ginger lilies will add color, fragrance and a tropical vibe to your home garden.

Ginger lilies grow best in full to part sun in rich, moist, well-drained soil. New stems emerge in late spring and quickly grow into upright stems with long, bold-textured leaves held horizontally or angled upright. The cane-like stems are topped with clusters of large, bright colored flowers starting in late spring to mid summer, often continuing through fall. Frosts or freezes will kill the above-ground stems, but rhizomes easily overwinter temperatures as low as 0°F (making them hardy into USDA Cold Hardiness Zone 7b) and produce new growth in late spring once warm weather resumes. Few pests or diseases affect ginger lily, and the only regular maintenance is to cut and remove the dead stems in late winter before new growth emerges.

Butterfly ginger is the type most widely grown and frequently shared as a pass-along plant. Butterfly ginger (Hedychium coronarium) is grown for its large fragrant white flowers. It grows 4 to 5 feet high and begins flowering in mid to late summer, continuing through fall. With a heavy sweet fragrance, a flowering clump of butterfly ginger smells heavenly in the garden and, as a cut flower, will easily perfume a large room! Butterfly ginger is not picky about growing conditions but prefers moist, good garden soil. This is the ginger flower most often used to make Hawaiian leis!

There are dozens of species and cultivars of Hedychium. Some of the ginger lilies that are often found in local nurseries or Master Gardener plant sales are listed below.

‘Dr. Moy’ variegated ginger lily (Hedychium ‘Dr. Moy’) is distinguished by white paint-like splashes on its leaves and fragrant, peachy-orange flowers. ‘Dr. Moy’ produces its first round of flowers from mid-July to August and a second crop in late-September to October.

‘Daniel Weeks’ ginger lily (Hedychium ‘Daniel Weeks’) is a perennial tropical ginger hybrid from Florida’s Russell Adams with hardiness to Zone 7. Growing to 6 to 7 feet high, it produces large dark throated golden-yellow inflorescences with the bonus of delightful evening fragrance. This vigorous clumping hardy ginger lily is the longest blooming, starting in early to mid summer and continuing to frost. It is considered by many as one of the best of all ginger lilies.

‘Disney’ scarlet ginger lily (Hedychium coccineum ‘Disney’) produces large, bright orange flower clusters on tall stems up to 7 feet in height. Foliage is very glossy with a reddish hue, and the overall effect of the clump of stems is very upright. Typically, all stems flower at the same time followed by a resting period before flowering again.

‘Pink Sparks’ ginger lily (Hedychium ‘Pink Sparks’) is a compact variety only growing 4 to 5 feet high. Terminal inflorescences are made up of many small bright pink flowers with very long stamens.

Ginger lily may be propagated by digging and dividing clumps or by cutting off sections of rhizome (making sure each section has at least one bud) and placing these in new locations for sprouting and growth. It’s best to divide or propagate plants before late summer so divisions have enough time to develop a new root system and/or stems before the cooler weather of fall slows growth.

References

Carey, Dennis and Tony Avent. 2010. Hedychium – A Hardy Ginger Plant for the Garden. Plant Delights Nursery, Inc., Raleigh, NC 27603. https://www.plantdelights.com/blogs/articles/ginger-plant-lily-variegated-hedychium-lilies. Accessed 9 June 2021.

Gilman, Edward F. 2015. Hedychium coronarium Butterfly Ginger, FPS-240. Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension, Gainesville, FL 32611. Original publication date October 1999. Reviewed February 2014. FPS-240/FP240: Hedychium coronarium Butterfly Ginger (ufl.edu). Accessed 9 June 2021.

by Gary Knox | Aug 31, 2020

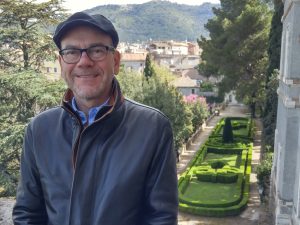

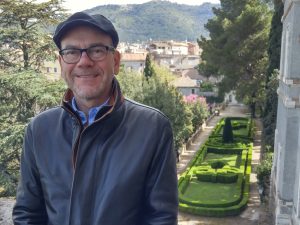

Gary Knox is professor of environmental horticulture and Nursery Crops Extension Specialist at the University of Florida/IFAS at the North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) in Quincy. Dr. Knox is heavily involved in research and extension on nursery/landscape problems like Rose Rosette Disease, Crapemyrtle Bark Scale, and invasive plants. On a more uplifting note, he also evaluates perennials for their attractiveness to pollinators, and new woody plants for their ornamental qualities and usefulness in Florida landscapes. These plant evaluation activities largely take place in “Gardens of the Big Bend,” a new botanical, teaching and evaluation garden established in 2009 and located on the grounds of NFREC. The Gardens are a collaboration of NFREC with Gardening Friends of the Big Bend, Inc. (GFBB), a nonprofit volunteer group of gardening enthusiasts and Green Industry professionals. Members of GFBB actively volunteer to develop, maintain and fund-raise for the Gardens as well as assist Dr. Knox with research and extension activities.

This 2019 photo shows Gary at the fabulous gardens and fountains of Villa d’Este in Tivoli outside Rome, Italy.

Gary’s current plant passions include magnolia, crapemyrtle, camellia, hydrangea, Southern bulbs, succulents, and palms (so many species, so little time!). It’s no secret that he is particularly fond of magnolias, going so far as to serve four years as president of Magnolia Society International (MSI), the organization supporting magnolia conservation and research. Gary’s roles with UF and MSI have taken him from Cuba to China and England to Ecuador promoting magnolia conservation and research. Furthermore, Gary is a “Johnny Appleseed” of the magnolia world by collecting rare Magnolia species to propagate and share them with botanic gardens in Florida and nationwide to help conserve these species in as many places as possible. The collection of Magnolia species at Gardens of the Big Bend has been named part of the National Collection of Magnolia by the Plant Collections Network, a collaboration of the American Public Gardens Association and USDA.

When not gardening at home, Gary and husband Ken particularly enjoy travel, whether across the country to visit family, or abroad to visit inspirational gardens and historical sites and to meet people from other cultures. Otherwise, you might find Gary meeting friends to play cards and board games, attending civil rights-oriented events, or collecting vintage restaurantware made in his hometown of New Castle, PA. With more than 30 years under his belt at UF/IFAS, Gary is looking forward to retirement, but he’s not quite ready for it yet!

Written by: Kelly Thomas – Agricultural/Food Scientist II with the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center

Written by: Kelly Thomas – Agricultural/Food Scientist II with the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center