by Pat Williams | Jan 22, 2021

For all my years in the classroom, I never let students say the “d-word” when discussing soil science. In some instances, we had a “d-word” swear collection jar of a quarter when you used the term and even today, I hesitate from spelling the word out in text due to feedback from all those I have corrected. In case you still need a clue on the “d-word”, it ends in irt.

As a horticulturist for 46 years, I have read, heard, and been told many secrets to growing good plants. I still hold firm that without proper knowledge of how soil works, most of what we do is by chance. Soil is a living entity comprised of parent material (sand, silt, and clay), air, water, organic matter (OM), and microorganisms. It is this last item which makes our soils come to life. If you have pets, then you know they need shelter, warmth, air, water, and food. From this point forward think of soil microorganisms as the pets in your soil. If you take care of them, they will take care of your plants.

Sandy soil without any organic matter at the Wakulla County Extension office.

There is a huge difference in habitat from a sandy soil to a healthy soil with a good percentage of OM (5% – 10%). In one gram of healthy soil (the weight of one standard paper clip), you can have bacteria (100,000,000 to 1,000,000,000), actinomycetes (10,000,000 to 100,000,000), fungi (100,000 to 1,000,000), protozoa (10,000 to 100,000), algae (10,000 to 100,000), and nematodes (10 to 100) (1). A teaspoon of healthy soil can contain over four billion organisms (2). These microorganisms are part of the soil food web and they form a relationship between soil and your plants. They help convert nutrients to useable forms and assist with other plant functions.

The question becomes how to take care of your soil pets. For years we have performed practices that compromise these populations. Growing up we put all of our grass clippings in the weekly trash. We know now how valuable those clippings are and to leave them be. Two practices still common today though are tilling and raking leaves.

Master Gardener Volunteer vegetable bed with organic matter added.

Tilling has a limited purpose. If I place a layer of organic matter on top of the ground, then tilling incorporates the OM which feeds my pets. Excess tilling of soil introduces large amounts of oxygen which accelerates the breakdown of OM thus reducing our pet populations over time. Another adverse result from tilling is disturbing the soil structure (how the parent materials are arranged) which can reduce pore spaces thus limiting water percolation and root growth. There is a reason agriculture has adapted no-till practices.

Raking leaves (supposedly the sign of a well-kept yard) is removing large amounts of OM. Do you ever wonder why trees in a forest thrive? All of their leaves fall to the ground and are recycled by the microorganisms. Each of those leaves contains macronutrients (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, sulfur, and magnesium) and micronutrients (boron, copper, chlorine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, and zinc) which are necessary for plant growth. You would be hard pressed to find all those nutrients in one fertilizer bag. So recycle (compost) your leaves versus having them removed from the property.

We are in our off season and tasks such as improving soil health should be considered now for soils to be ready in spring. Remember a little organic matter at a time and never work wet soils. As your OM levels build over the years, remember to change your watering and fertilizing schedules as the soil will be better adapted at holding water and nutrients. Soil tests are still recommended before fertilizing.

If you would like more tips on improving your soil, contact me or your local county horticulture extension agents. For a more in depth look at caring for your soils, read The Importance of Soil Health in Residential Landscapes by Sally Scalera MS, Dr. A.J. Reisinger and Dr. Mark Lusk (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ss664).

- Chapter 2: Soils, Water, and Plant Nutrients. Texas Master Gardener Training Manual.

- The Importance of Soil Health in Residential Landscapes. 2019.

by Pat Williams | Oct 21, 2020

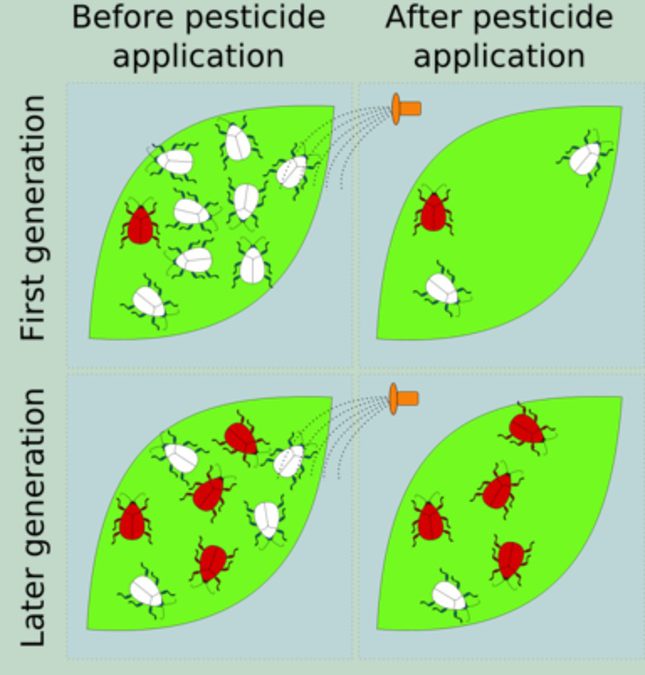

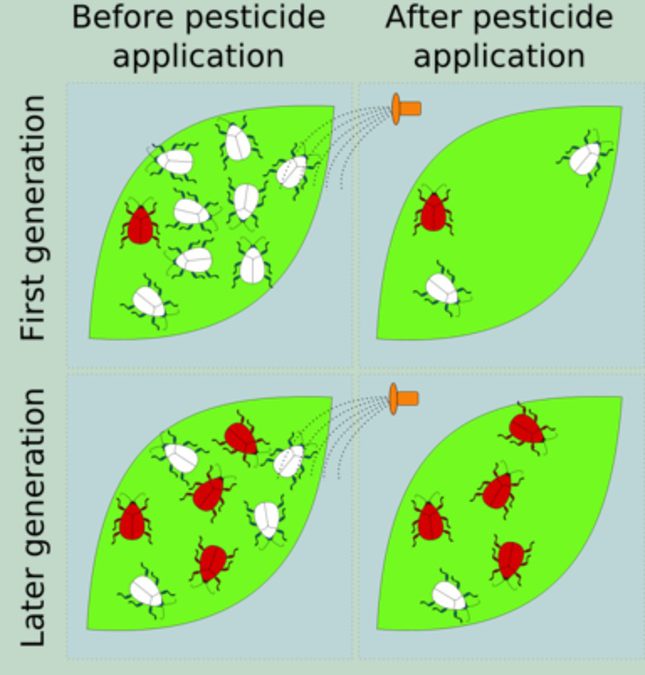

Normally, you will have one of four answers: “yes”, “no”, “I don’t know” or “what are super bugs?” The answer to the last one is an insect or other pest that has become resistant to chemical treatments through either natural selection (genetics) or an adaptive behavioral trait.

The next question is do you treat insect or pest problems at home with a purchased EPA registered chemical (one purchased from the nursery or other retailer)? If you answered yes, then the next question is how many times in a row do you apply the same chemical? If you only use one chemical until the product is used up, then you might be creating super bugs. Do you ever alternate chemicals and if you answer yes, do you understand chemical Modes of Action (how the pesticide kills the pest)? If you do not, then chances are the rotating chemicals might act in the same way. Thus, you are creating super bugs because in essence you are applying the same chemical with different labels.

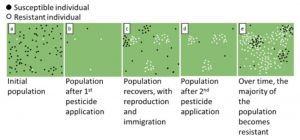

Click on image for a larger view. Taken from https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in714.

One of the first ways to reduce creating super bugs is to practice Integrated Pest Management (IPM). The very last step of an IPM philosophy is chemical control. You should choose the least toxic (chemical strength is categorized by signal words on the label: caution, warning, and danger) and most selective product. A chemical label advertising it kills many pests is an example of a non-selective chemical. You want to choose a chemical that kills your pest or only a few others. In Extension education, you will always hear the phrase “The label is the law.” To correctly purchase a chemical, you must first correctly identify the pest and secondly the plant you want to treat. If you need help from Extension for either of these, please contact us. Before purchasing the chemical, always read the whole label. You can find the label information online in larger print versus reading the small print on the container.

IRAC phone app.

You now have the correct chemical to treat your pest. Wear the recommended personal protective equipment (PPE) and apply according to directions. If your situation is normal, the problem is not completely solved after one treatment. You might apply a second or third time and yet you still have a pest problem. The diagram explains why you still have pests or more accurately super bugs.

Now the last question is how do we really solve the problem given that chemicals are still the only treatment option? A bit more work will greatly help the situation. You need to download the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) guide and find the active ingredient on your chemical label (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pi121 or https://irac-online.org/modes-of-action/ and select the pdf). If you are like me, you can just download the IRAC MoA smartphone app and type in the active ingredient; otherwise, Appendix 5 in the pdf has a quick reference guide. Either way, you will know the Group and/or Subgroup. A lot of commonly purchased residential chemicals fall within 1A, 1B or 3. The successful treatment option is to select chemicals from different group numbers and use them in rotation. If you start practicing this simple strategy, your treatment should be more successful. Then when someone asks if you are creating super bugs, your answer will be no.

If you have any questions about rotating your chemical Modes of Action, please contact me or your local county Extension agent. For more resources on this topic, please read Managing Insecticide and Miticide Resistance in Florida Landscapes by Dr. Nicole Benda and Dr. Adam Dale (https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in714).

by Pat Williams | Oct 1, 2020

Pat is the County Extension Director and the Agriculture/Horticulture/Natural Resources agent for UF/IFAS Extension Wakulla County while also serving as the Master Gardener Volunteer Coordinator for both Franklin and Wakulla counties.

Pat by their outdoor mural at the Extension office.

He earned his doctorate from Texas A&M University in horticulture, a M.S. degree from Kansas State University in horticultural therapy, a B.S. degree in ornamental horticulture/floriculture from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and an A.S. degree in ornamental horticulture from Crafton Hills College.

Over his horticulture career that started at age 13 working for Chrysanthemum Gardens in Crestline, CA, he has resided in 10 different states with a wide range of environmental influences (CA, KS, NJ, ME, NY, WA, TX, KY, TN and FL). He has held various positions in his career from teaching adults with developmental disabilities in NJ and ME, designing, installing and maintaining landscapes, landscape construction, being a horticultural therapist in New York City, working for the USDA in WA, teaching in a TX federal prison for his Extension appointment, teaching horticulture in a TN high school and was an university horticulture professor for 14 years in KY after teaching at Kansas State University, Washington State University and Texas A&M University as a teaching assistant. He started with the University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences in April 2017 as the Sarasota County Residential Horticulture Agent/Master Gardener Volunteer Coordinator and transitioned to the Wakulla County Extension office in June 2020.

Teaching and greenhouse growing are his professional joys. Florida is the first state where there has not been a greenhouse to play in and he misses it greatly, however Extension does offer many opportunities to share his passion for plants and outdoors with a new group of learners. Otherwise Pat grew up on the beaches and ski resort areas of southern CA and still finds solace today relaxing on the beach or kayaking. He has traveled a bit visiting 49 states with only Hawaii to go. When indoors he would rather be baking or cooking in the kitchen as his second career choice would have been a chef. There is usually a yard full of flowers, herbs and vegetables and he is an extremely proud FSU Seminole Dad to Tara, a 2020 graduate.

Pat wears many hats at the Wakulla office and handles topics other than 4-H/Youth Development or Family and Consumer Sciences. Once again he finds himself in a transition adapting to the new horticultural environment of Florida’s panhandle and developing more programs in agriculture and natural resources. Please feel free to reach out to see how the UF/IFAS Extension Wakulla County can be of assistance.

by Pat Williams | Sep 14, 2020

Did you ever want to grow something for the dinner table in your yard, but said “I don’t have the space”, or “I don’t have the time”, or “it seems like a lot of hard work or even I have restrictions because of the homeowner’s association I live in”?

If so, then foodscaping might be the answer to growing food in your yard. Landscape beds have traditionally been planted with trees, shrubs, groundcovers, flowers and even vines while edibles were relegated to garden plots containing vegetable and herbs. Foodscaping is a growing trend that takes edibles from formal vegetable plots into landscape beds.

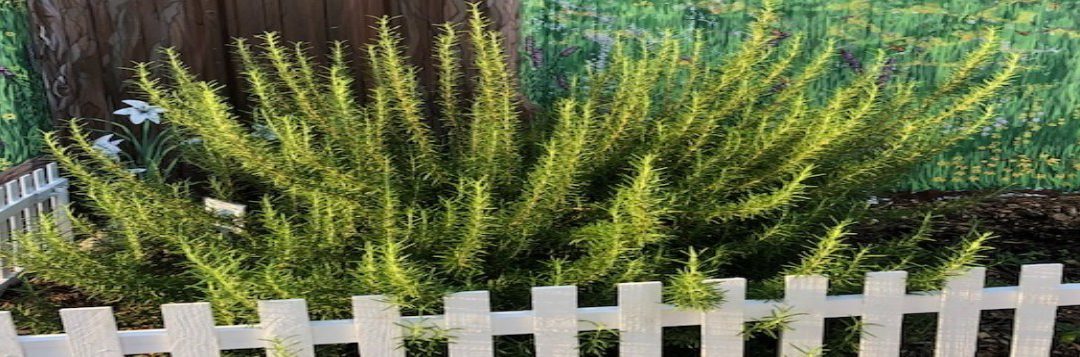

Rosemary in the UF/IFAS Extension Wakulla entrance bed.

Foodscaping works for both newly planted landscapes and established ones. Only a few square feet are needed to begin. When most new landscapes are planted, they space plants apart for future mature growth. Until the shrubs fill in, you have usable space. The same holds true for established landscapes. Sometimes there is empty space. Whatever the cause, there now is a foodscaping opportunity.

Some of the best examples of beginning foodscaping plants are herbs and greens. A good number of cooking herbs are perennials and can add seasonal accent to the yard and flavor in the kitchen. Some examples are oregano*, thyme, rosemary, sage, lemongrass, chives, garlic chives, winter savory, mints*, chamomile, lavender, and lovage (* containers will help control the spread).

Potted chocolate mint between red salvia and yew.

Some annuals herbs include dill, fennel, cilantro/coriander, basil, garlic, sweet marjoram (perennial but acts like an annual in colder areas) and tarragon. These herbs are compact, just one or two plant in a space with a bit of room to grow is all that’s needed. Other vagetables that offer a seasonal groundcover look are greens like assorted leaf lettuces, spinach, mustard, bok choy, collards, sorrel, burnet, parsley and kale. These herbs and vegetables attract the senses with their colors, textures, and fragrances.

Once you get the hang of these easier foodscaping plants, you can branch out into more traditional garden favorites like potatoes, sweet potatoes, green beans, peas, beets, radishes, celery or anything that fits the space and cultural/environmental requirements.

Besides having some quick and easy items to eat from the yard, you are also doing your bit for the environment by reducing vehicle travel, which reduces your carbon footprint. And if you have extra, share with your neighbors and encourage them to foodscape as well. For more information check out https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/design/types-of-gardens/foodscaping.html.