by Mary Salinas | Oct 14, 2015

Cogongrass dominating the landscape. Photo credit: Charles T. Bryson, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org.

A U.S. Forest Service grant is again available to assist non-industrial private landowners with the cost of controlling cogongrass. Applications will be accepted starting October 15, 2015. The program reimburses landowners for 50% of the cost for two consecutive years with a maximum reimbursement of $10,000 for each year.

Cogongrass is one of the worst invasive plant species in Northwest Florida as it marches through natural areas and literally chokes out our desirable native vegetation as it goes. The underground rhizomes continually expand patches of the grass in every direction and its prolific seed production carries infestations to new areas.

Note the off center midrib along the leaf blade. Photo credit: Chris Evans, Illinois Wildlife Action Plan, Bugwood.org.

There are several ways to accurately identify cogongrass. The leaf blades are flat with serrated edges and tend to be yellowish-green in color. The midrib which runs lengthwise up each leaf blade is white and is distinctly off-center. The seed head which arises in the spring is a fluffy white plume. Since it spreads through rhizomes, cogongrass is often seen in expanding circular patches.

The fluffy white plume of the seedhead. Photo credit: Chris Evans, Illinois Wildlife Action Plan, Bugwood.org.

If you need assistance with the identification of cogongrass, please consult your local Extension office.

For more information:

Cogongrass Treatment Cost-Share Program

Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica) Biology, Ecology, and Management in Florida Grazing Lands

by Matt Lollar | Sep 23, 2015

Armyworms come in a wide range of colors and sizes. A few of the prominent species living in Florida are beet, southern, and fall armyworms. And the term “living” is not an exaggeration, because Florida is one of the lucky states where it is warm enough for armyworms to overwinter. They are the snowbirds that never leave!

Armyworm damage on a lawn. Credit: Purdue University

Armyworms are notorious for unanticipated invasions. They feed on most turfgrass species and most vegetable crops, but they prefer grassy vegetable crops such as corn. Armyworms feed in large groups and their feeding has been described as “ground moving” in lawns. They feed during cooler times of the day (morning and evening) and they roll up and rest under the vegetative canopy (in the thatch layer in turf and in the base of leaves in vegetables) during the heat of the day.

Armyworms are difficult to control because of their spontaneity. However, in the lawn they hide in the thatch during the heat of the day. Over watering and fertilization can increase the amount of thatch. It is important to follow UF/IFAS guidelines for home lawn management. A good weed control program can also help to deter armyworms, because weeds serve as an alternate food source.

Numerous chemical control options are available, but softer chemicals such as horticultural oils and insecticides containing the bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis are recommended as a first line of defense. Insecticides should be applied in the morning or evening during feeding time. For additional control strategies and basic information please visit the UF/IFAS Armyworm Publication Page.

Armyworm feeding on a young corn plant. Credit: University of Illinois

by Sheila Dunning | Sep 16, 2015

“We have replaced this grass several times over the past few years; and it’s dying again.” I have heard this complaint too many times this summer. Last summer’s heavy rain, the stress of January’s icy weather, and this year’s extended summer have contributed to widespread outbreaks of Take-All Root Rot, a soil-inhabiting fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis var. graminis.

Symptoms of Take-All-Root-Rot. Photo credit: Sheila Dunning, UF/IFAS.

This disease causes yellow grass patches ranging in diameter from a few inches to more than 15 feet. The symptoms first appear in the spring, but the disease can persist all summer and survive the winter. Over time, the entire area dies as the root system rots away. The pathogen is naturally present on warm-season turfgrass roots. High rainfall and stressed turfgrass trigger the disease.

Since the roots are affected, they are not able to efficiently obtain water or nutrients from the soil, nor are they able to store the products of photosynthesis, which result in the loss of color in the leaves. By the time the leaf symptoms appear, the pathogen has been active on the roots for several weeks, probably longer; the disease has been there potentially for years. If the turfgrass is not stressed, leaf symptoms may never be observed.

This disease is very difficult to control once the aboveground symptoms are observed. Measures that prevent or alleviate stress are the best methods for controlling the disease. Any stress (environmental or manmade) placed on the turf weakens it, making it more susceptible to disease. Remember, that every maintenance practice, fertilizer application, and chemical (especially herbicide), application has an impact on turfgrass health. Cultural practices that impact the level of stress experienced by a lawn include:

- proper turfgrass species selection

- mowing at the correct height

- irrigation timing, frequency and volume

- fertilizer: nitrogen and potassium sources and application quantities

- thatch accumulation, and

- soil compaction

The selection of turfgrass species should be based on existing soil pH, sunlight exposure, use of the area and planned maintenance level.

Mower blades must be sharp to avoid tearing of the leaves. Additionally, turfgrasses that are cut below their optimum height become stressed and more susceptible to diseases, especially root rots. When any disease occurs, raise the cutting height. Scalping the grass damages the growing point. Raising the cutting height increases the green plant tissue available for photosynthesis, resulting in more energy for turfgrass growth and subsequent recovery from disease.

If an area of the lawn has an active fungus, washing or blowing off the mower following use will reduce the spread of the disease to unaffected areas.

The amount of water and the timing of its application can prevent or contribute to disease development. Most fungal pathogens that cause leaf diseases require free water (rainfall, irrigation, dew) on the leaf to initiate the infection process. Irrigating every day for a few minutes is not beneficial for the turfgrass because it does not provide enough water to the root zone, but it is beneficial for turfgrass pathogens. It is always best to irrigate when dew is already present, usually between 2 and 8 a.m., and then only apply enough water to wet the root zone of the turfgrass.

Excessively high nitrogen fertility contributes to turfgrass diseases. The minimum amount required for the grass species should be applied. Potassium (K) is an important component in the prevention of diseases, because it prevents plant stress. Application of equal amounts of nitrogen and potassium is recommended for turfgrass health. When turfgrass roots are damaged from disease, it is beneficial to apply nutrients in a liquid solution. However, nitrate-nitrogen increases the severity of diseases, so their use should be avoided when possible. Ammonium-containing fertilizers are the preferred nitrogen sources.

Heavy liming has also been linked to increases in Take-All Root Rot. Since most turfgrasses can tolerate a range of pH, maintaining soil at 5.5 to 6.0 can suppress the development of the pathogen. When the disease is active, frequent foliar applications of small amounts of nutrients is necessary to keep the turfgrass from declining.

Additional maintenance practices that need to be addressed are thatch removal and reduction of soil compaction. Excessive thatch often causes the mower to sink which can result in scalping and reducing the amount of leaf tissue capable of photosynthesizing. Thatch and compacted soil prevent proper drainage, resulting in areas remaining excessively wet, depriving root systems of oxygen. Since recovery of Take-All-Root-Rot damaged turfgrass is often poor, complete renovation of the lawn may be necessary. Removal of all diseased tissue is advised.

As a native soil-inhabiting pathogen, Take-All-Root-Rot cannot be eliminated. However, suppression of the organism through physical removal followed by proper cultivation of the new sod is critical to the establishment of a new lawn. Turfgrass management practices, not chemicals, offer the best control of the disease.

It is acceptable to use fungicides on a preventative basis while rooting in the sod. Azoxystrobin, fenarimol, myclobutanil, propiconazole, pyraclostrobin, thiophate methyl, and triadimefon are all fungicides that can be utilized to prevent disease development while having to excessively irrigate newly laid sod. Ideally, the turf area should be mowed and irrigated prior to a fungicide application. Unless the product needs to be watered in, do not irrigate for at least 24 hours after a chemical treatment. Do not mow for at least 24 hours, to avoid removal of the product attached to the leaf blades.

With all the stresses that our lawns have experienced, it is very important to continue monitoring the turf and be cautious about the cultural practices being used. Take-All Root Rot is likely to flourish. Do not encourage its development. A pathology test with the University of Florida Laboratory can confirm the presence of the disease causing organism. Before resodding again, have the dying sod tested.

For information and the submission form go to:

Sample Submission Guide

For more information on the disease go to:

Take-All-Root-Rot

by Beth Bolles | Sep 16, 2015

Just when you think your battle against weeds is over for the summer, cooler nighttime temperatures and shorter days spark the beginning of a new crop of your least favorite plants. The question of many homeowners is: how did all the weeds get into my landscape?

There are many ways that weeds make it to the landscape. They can be brought in with new soil, mulch, container plants, dropped by birds, delivered on the fur of animals, carried by wind, or on the deck of a lawn mower. If that is not enough to depress you, then also realize that regardless of outside sources of weeds, your landscape already has plenty onsite that you don’t even know about.

In the soil, there is a large number of weed seeds ready to germinate when the conditions are just right. Understanding how your common landscape practices can encourage or discourage the germination of these seeds, can help you begin to manage some weed infestations.

Many of the seeds of common annual weeds are very small. They require exposure to sunlight in addition to the proper temperatures and moisture to germinate. Sunlight is critical, though, and seeds will not germinate without adequate sunlight. If the small seeds are deep in the soil, you will probably never know they are there. When you turn soil or disturb soil such as when installing plants, you bring the small seeds close to the surface and closer to light. They can then be stimulated to germinate. The next thing you know, you have an area covered in weed seedlings.

As mulch thins, small seeds of weeds are stimulated by sunlight to begin growing.

What does this mean for your gardening practices? Try your best to block sunlight from hitting exposed soil. You can do this by keeping a healthy turf, free of thinning spaces. A 2 to 3 inch layer of mulch in plant beds and vegetable gardens will reduce weed seed germination. Finally, when you are installing plants in an established bed, try not to mix soil with surrounding mulch. Seeds will easily germinate within the mulch if it becomes mixed with soil.

It is inevitable that your landscape will have some weeds but a few easy gardening practices can reduce some of your weed frustrations.

For more information:

Gardening Solutions: Weeds and Invasive Plants

Improving Weed Control in Landscape Planting Beds

by Beth Bolles | Aug 26, 2015

It would seem that landscapes are filled with pests ready to devour our favorite plants. We can often see evidence of pest damage in the form of leaf curls, stippled leaves, or chewed holes in foliage. How do plants survive with all the pest threats without intervention from people?

Many plants have their own alert system to help manage a plant-feeding insect attack. When tissues are damaged by plant feeders, the plant releases volatile chemicals that serve as signals for many beneficial insects. Predators such as lady beetles, lacewings, and predatory bugs ‘pick up’ the chemical signals and fly to the injured plants to find their prey.

Ladybeetle larvae will eat many soft-bodied pests.

An interesting part of this occurrence is that the release of chemicals by one plant can stimulate other surrounding plants to build up their chemical defenses against future pest feeding.

The key lesson for all gardeners is that there are many natural processes going on without our knowledge. Instead of immediately applying a broad-spectrum insecticide at the earliest sign of pest feeding on a plant, give the predators a chance to provide you with a free and environmentally sound form of pest control.

by Sheila Dunning | Aug 13, 2015

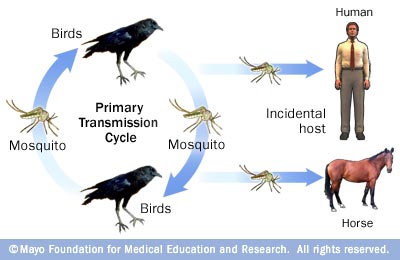

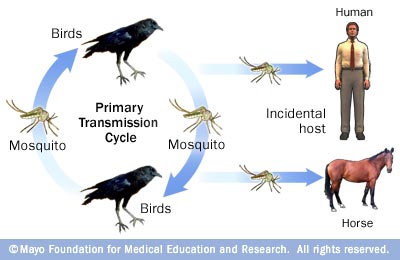

University of Florida researchers maintain a constant vigilance on the potential for mosquito-borne illness concerns. UF/IFAS Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory in Vero Beach tracks rainfall, groundwater levels, mosquito abundance, wild bird populations and virus transmission to animals including horses and sentinel chickens. When mosquito infection rates reach the levels that can infect humans, alerts are sent out. Through the Florida Department of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Alert Network issues advisories on a weekly basis to those counties at risk. Such an alert was issued for Gadsden, Polk and Walton Counties for the week of July 19-25, 2015. Unfortunately, the first 2015 confirmed human case of West Nile Virus illness in Florida occurred in Walton County shortly thereafter. It was just another reminder for people to take action to reduce their potential for mosquito development in their landscape.

University of Florida researchers maintain a constant vigilance on the potential for mosquito-borne illness concerns. UF/IFAS Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory in Vero Beach tracks rainfall, groundwater levels, mosquito abundance, wild bird populations and virus transmission to animals including horses and sentinel chickens. When mosquito infection rates reach the levels that can infect humans, alerts are sent out. Through the Florida Department of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Alert Network issues advisories on a weekly basis to those counties at risk. Such an alert was issued for Gadsden, Polk and Walton Counties for the week of July 19-25, 2015. Unfortunately, the first 2015 confirmed human case of West Nile Virus illness in Florida occurred in Walton County shortly thereafter. It was just another reminder for people to take action to reduce their potential for mosquito development in their landscape.

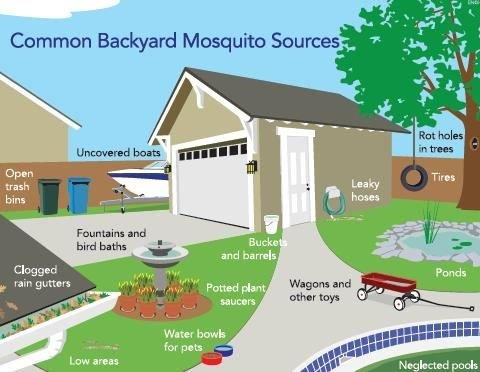

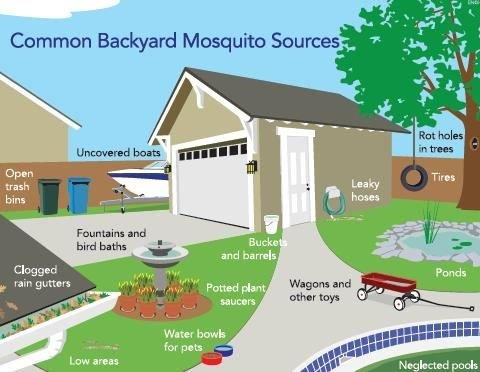

With all the quick afternoon thunderstorms and frequent irrigation events, now is the time to check out where the water is collecting in your yard. The female Culex nigripalpus mosquitoes lay their eggs in temporary flood water pools; even very small ones such as pet watering bowls, bird baths and upturned Magnolia leaves. Dumping out the collection containers every couple of days can greatly reduce the population.

Becoming infected with West Nile Virus is not easy. Mosquitoes usually obtain the virus by feeding on infected wild birds, many of which have migrated from areas that have ongoing West Nile Virus outbreaks. Once the mosquito has drawn infected blood from the bird, the virus goes through a temperature-dependent incubation period within the mosquito. Then, when the infected mosquito “bites” a human or horse the virus mixed in saliva is released into the blood stream of the second host. West Nile Virus is not transmitted from one human to another. Nor is it transmitted from bird to human or from horse to human.

Thanks to a devoted set of researchers and government public health officials, here in Florida we are able to monitor mosquito-borne illnesses quickly and effectively. Additional partners, such as local veterinaries, sentinel bird stations and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) serve as reporters for virus population. Should an individual come across dead birds without an obvious cause, reporting them to the FWC at www.myfwc.com/bird/ is the best thing to do.

As for protecting yourself, here are a few pointers:

As for protecting yourself, here are a few pointers:

Stay indoors at dusk (peak mosquito biting time).

If you must be outside, wear long sleeves and pants and/or mosquito repellents containing the active ingredient DEET.

Repair torn door and window screens.

Remove unnecessary outside water sources.

Flush out water collected in outdoor containers every 3-4 days.

Disturb or remove leaf litter, including roof gutters and covers on outdoor equipment.

For additional information, contact your local Extension office about obtaining a free Florida Resident’s Guide to Mosquito Control.